Crisscrossed streams completely covered with red fins that splash ferociously while contrasted against wild deep green tundra, creating 40,000 square miles of pristine country. This describes the untouched tributary streams of the Bristol Bay watershed, which is home to the world’s largest run of sockeye salmon. Bristol Bay produces about 50% of the world’s wild salmon population, generating $1.5 billion a year, providing an annual 20,000 jobs in the U.S., and supporting 4,000-year-old Native Alaskan cultures (World Wild Life Fund). Bristol Bay supports one of very few wild salmon runs left in the world, which makes it a site of international importance. But this untouched watershed is threatened by the proposed Pebble Mine that could potentially destroy one of the rarest places left on earth.

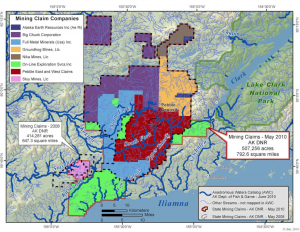

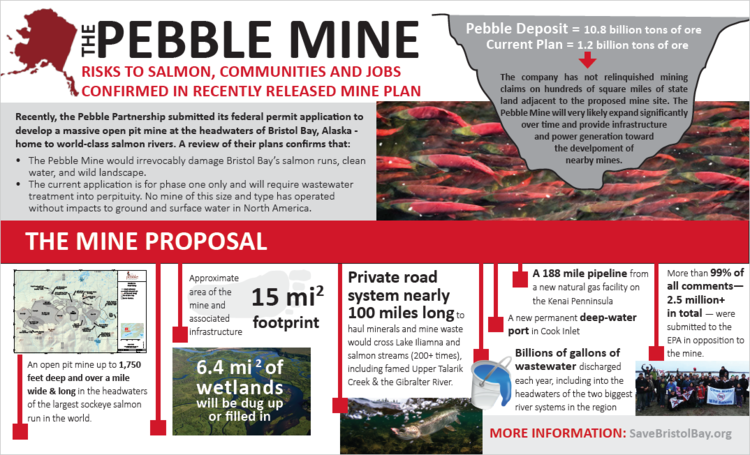

The proposed Pebble Mine, led by The Pebble Partnership, would be located 200 air miles from Anchorage, Alaska. The copper, gold, and molybdenum mineral deposits in this region were discovered in 1987, and the first exploration drilling started in 1988. If built, Pebble Mine would be the largest open pit mine in North America. The mine would span over 15 square miles of Bristol Bay’s watershed; it would be larger than the size of Manhattan Island and deeper than the Grand Canyon. Pebble Mine would require the world’s largest earthen dam to be built measuring over 700 feet high and several miles long. The dam would create a 10 square mile wide containment pond, intended to hold 2.5 – 10 billion tons of mine waste (sulfuric acid) that Pebble Mine would produce – enough to completely bury the city of Seattle, WA.

The Pebble Partnership’s message to the public is that they could bring jobs and infrastructure to communities in Bristol Bay, in harmony with the environment. Yet, the EPA report, “An Assessment of Potential Mining Impacts on Salmon Ecosystem of Bristol Bay Alaska” identifies the risks from large-scale mining projects like the proposed mine. It is clear that environmental harmony is not possible. The environmental risks are too large for the important natural resources that would be affected. Active mine sites leave behind huge amounts of mine waste, with environmental damage and a potential threat to living organisms and human health (Bini et al. 2017). The mine would not just affect salmon populations; other wildlife in Bristol Bay are intimately connected to and dependent on salmon. Changes in the fishery would affect the abundance and health of all wildlife populations in this ecosystem.

On May 1, 2017, CEO of Pebble Partnership Tom Collier asked the head of EPA, Scott Pruitt, to reverse environmental regulations on Bristol Bay that were placed by former President Barack Obama (CNN). Pruitt agreed to reverse these regulations after a 30-minute meeting with the Pebble Partnership CEO. The regulations that were reversed included a protection called the “Clean Water Act Designation”, set in place to specifically stop further advancements of the mine. This discussion outraged fishers, conservationists, and local members of the Bristol Bay community.

“After all the progress that we have made to stop this, this felt like a slap in the face”

-Erwin Stroosma, a fisherman who has spent the last 30 seasons in Bristol Bay

But in January 2018, the EPA released a news release for Scott Pruitt, stating that he would follow through with his “promise to restore the rule of law and process to the previous Administration’s actions to restrict mining in Bristol Bay”. After hearing directly from stakeholders and community members in Alaska, the EPA is suspending its process to withdraw proposed restrictions, leaving them in place while more information about the potential impacts on the natural resources is received by the EPA. But what does Scott Pruitt’s previous actions say about whether or not the land will continue to be protected? “We are cautiously optimistic” says Erwin Stroosma.

If the environmental risks of this proposed mine are not enough for one to believe that this plan should be thrown out, then listen to the stories of commercial, recreational, subsistence fishers and Native community members that are tied to this resource. Sophie O’Connell, a fisherwoman who grew up in Bristol Bay stated, “One can’t help but worry about how negatively affected the salmon runs will be, especially when fishing is your main source of income like it is for me.” O’Connell has been fishing in Bristol Bay for over 15 years. This resource is woven into the culture of Bristol Bay. It is the heart of many communities and the reason why I travel back every summer. This watershed’s importance to so many types of people alone should be a good enough answer to stop this proposed mine. People’s livelihoods are at stake if this mine were to be put in place.

We have to protect Bristol Bay for the people and the salmon!

Check out:

http://www.savebristolbay.org/home/

Related Articles:

https://www.ecowatch.com/last-great-salmon-rivers-2541794289.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/24/opinion/sunday/gold-mine-salmon.html

Leave a Reply