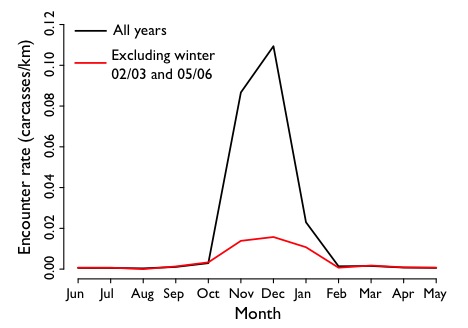

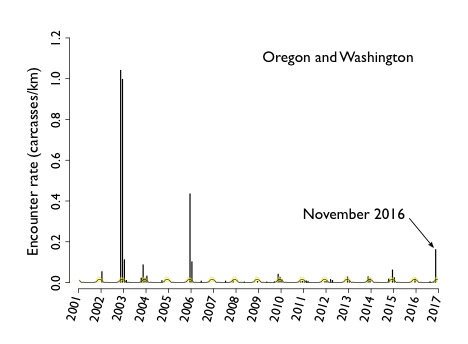

COASSTers surveying along the Lower 48 West Coast know that winter brings cold, darkness, rain… and grebes. This winter season, COASST has received a flurry of messages about an uptick in beachcast grebes. Is this normal? Is something going on? The answers are yes, and yes.

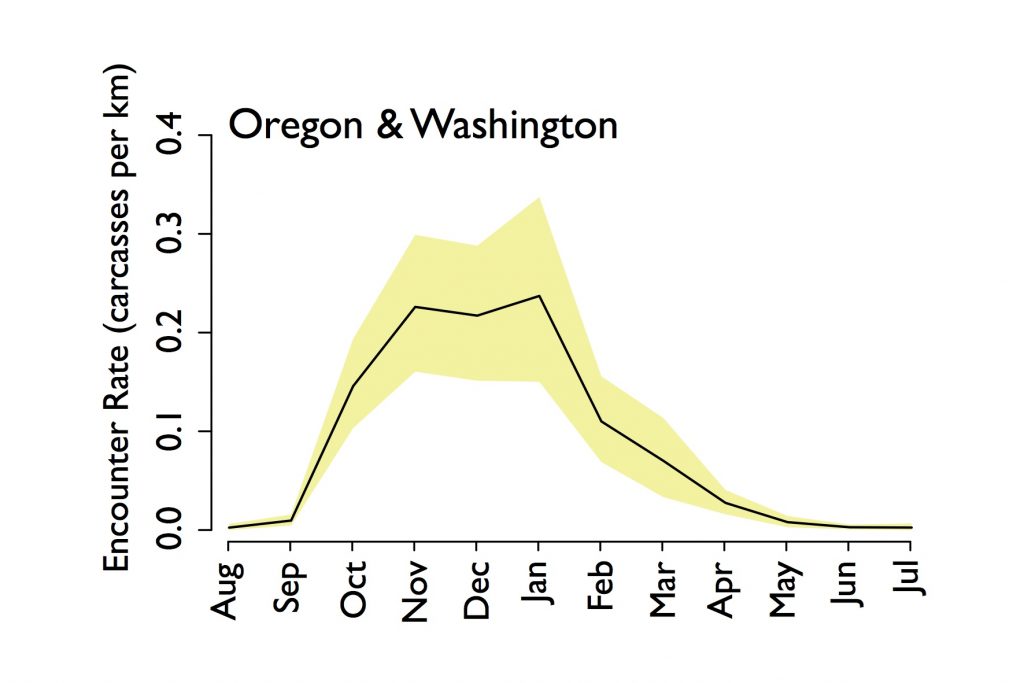

Grebes breed inland on freshwater lakes and ponds throughout western North America, migrating to coastal locations post-breeding from the Gulf of Alaska south to Mexico, and including inside waters like the Salish Sea, San Francisco Bay, and the Gulf of California. By November, the chance of encountering a grebe along the Pacific Northwest outer coast has risen from essentially zero to about one grebe per 5 kilometers. And that’s the average, some places and some years see much higher spikes.

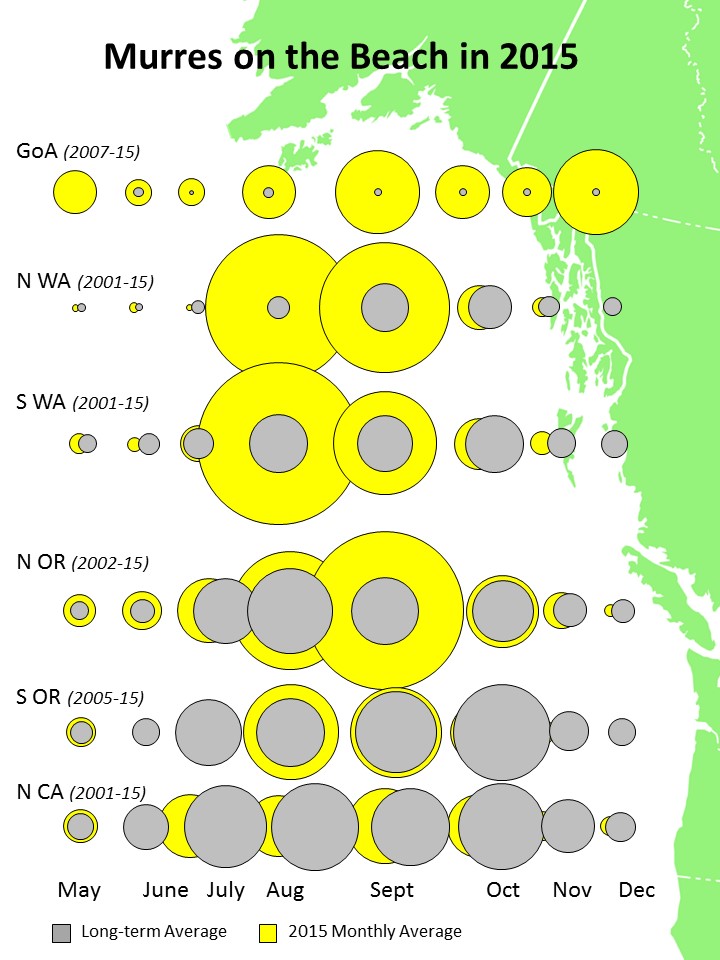

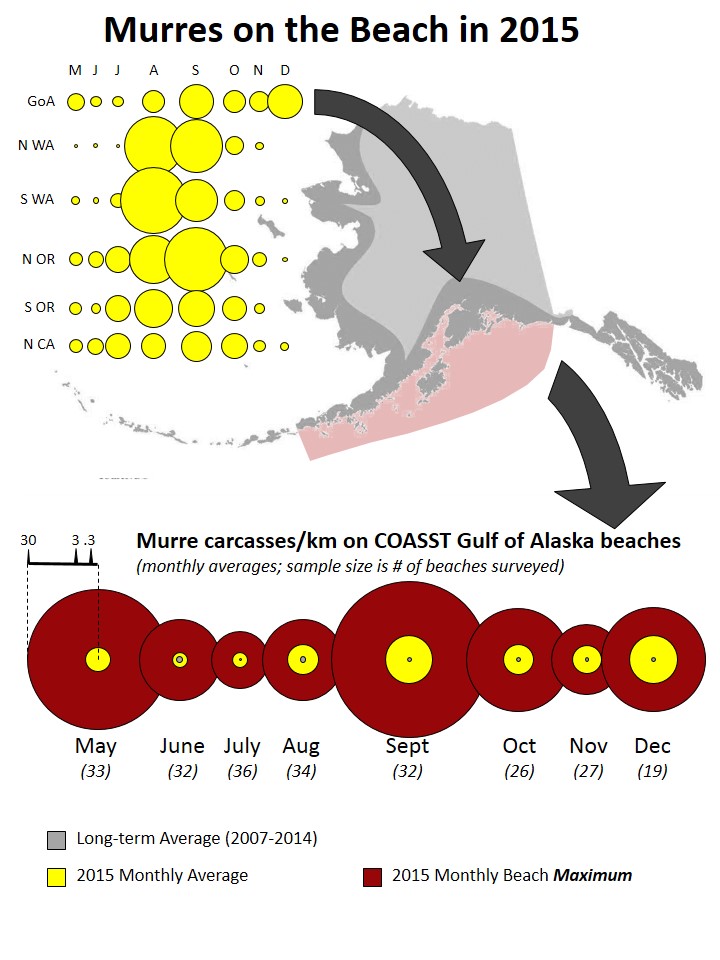

The black line traces the average or “baseline” pattern of how many grebes are found per kilometer of beach length over the year (where numbers less than one mean you would need to walk more than a kilometer to find a grebe). The yellow area to either side of the line is the range over which 95% of the actual variability in that central signal lies. If we record a month and year that is absolutely lower (or higher) than the yellow area, we pay attention.

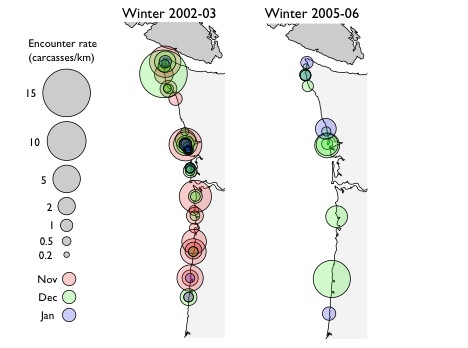

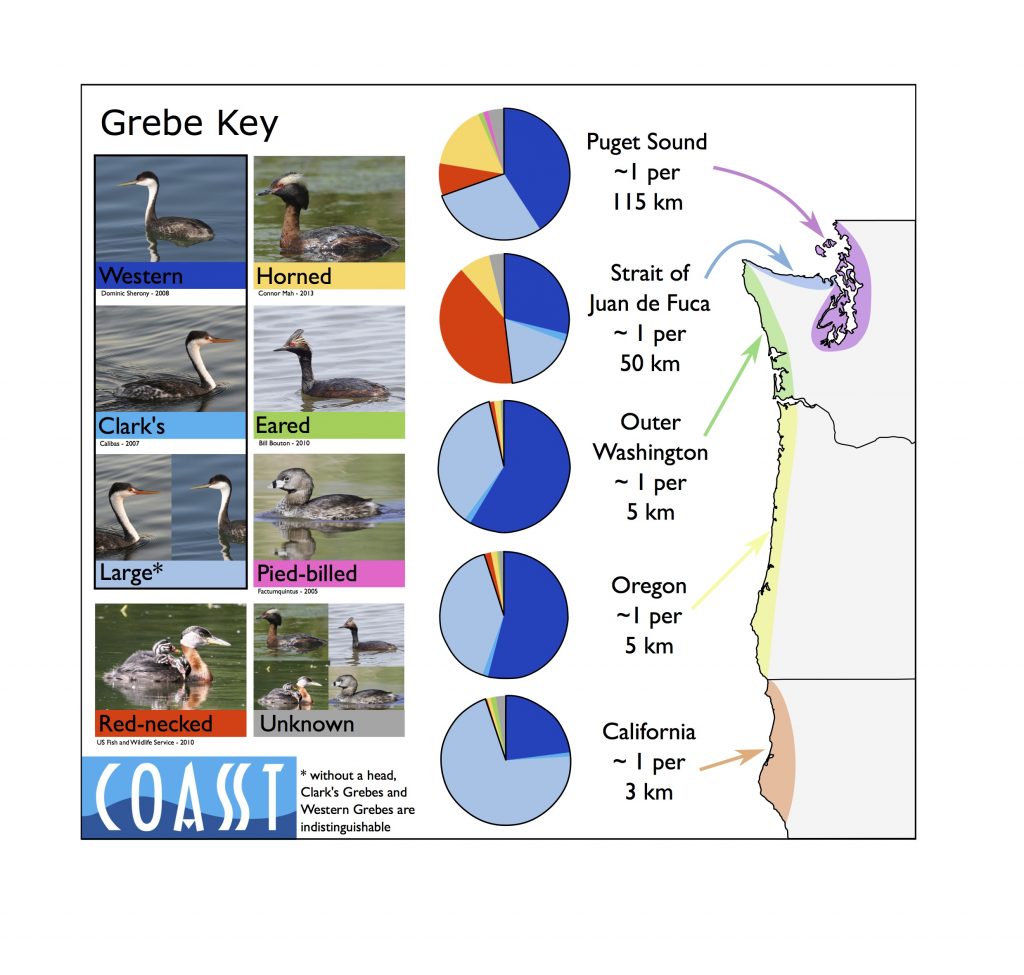

Most of the grebes washing ashore on COASST beaches are large grebes, and most of those are Western Grebes. The pie charts in the map graphic indicate the proportion of grebes found in each region identified to species. Dark blue is Western, turquoise is Clark’s, and light blue is when we can’t tell the difference.

What?!? Are we really that bad at identification? Nope. Turns out that a headless large grebe is impossible to differentiate as Western or Clark’s. And that’s because the best character is whether the dark|light plumage line on the face puts the eye in the dark feathers (Western) or the white feathers (Clark’s).

Side note: headless grebes, or more commonly a grebe with the neck skin inverted and pulled over the face so that only the bill is poking out from this macabre inside out turtleneck are the victims of raptors who literally skin their dinner to expose the breast meat. Light blue pie slice? – that’s a raptor signal.

There are several really cool patterns to note in this graphic:

- First, the proportion of the grebe pie that is Western or Clark’s is HUGE – almost every grebe found along the outer coast is one or the other.

- Second, the “raptor signal” is also pretty large, especially in California.

- Third, the chance of finding a beachcast grebe is vastly different, depending on where you are. From November-February (i.e. the peak season for Grebes) you need only walk ~3 km in California to find a grebe on average, whereas in Puget Sound it’s a much longer trek: 115 km of beach before finding a grebe. And there’s a south to north pattern – more towards the south, less as you go north, and a serious decline as you round the corner into the Salish Sea.

- Fourth, while the Salish Sea may not have as many grebe carcasses on beaches, the variety – the biodiversity – of grebes is much higher. Horned Grebes, Pied-billed Grebes, even Eared Grebes wash in. Want a chance of finding a Red-necked Grebe? Eschew the outer coast and head for the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

When the days start to lengthen and winter loses it’s grip on the Pacific Northwest, grebes stop washing in. By March-April, a grebe carcass is a very rare occurrence on a COASST beach. And that’s because these long-necked divers have left their seaside wintering grounds for their freshwater breeding sites, where they’ll build a floating nest, raise a brood, and start the migratory cycle all over again.