by Eric Wagner (who has a new book out: “Penguins in the Desert“)

In addition to writing for COASST from time to time I’m also a volunteer, which means I went to a training, which means that, midway through said training, I watched Hillary Burgess, COASST’s Science Coordinator and the trainer for the day, pull out a big plastic bin full of bird specimens for all of us to practice measuring and identifying. And as I was measuring the chords of variably patterned wings, or examining the webbing between the toes of a foot, I found myself wondering: Where exactly did they come from?

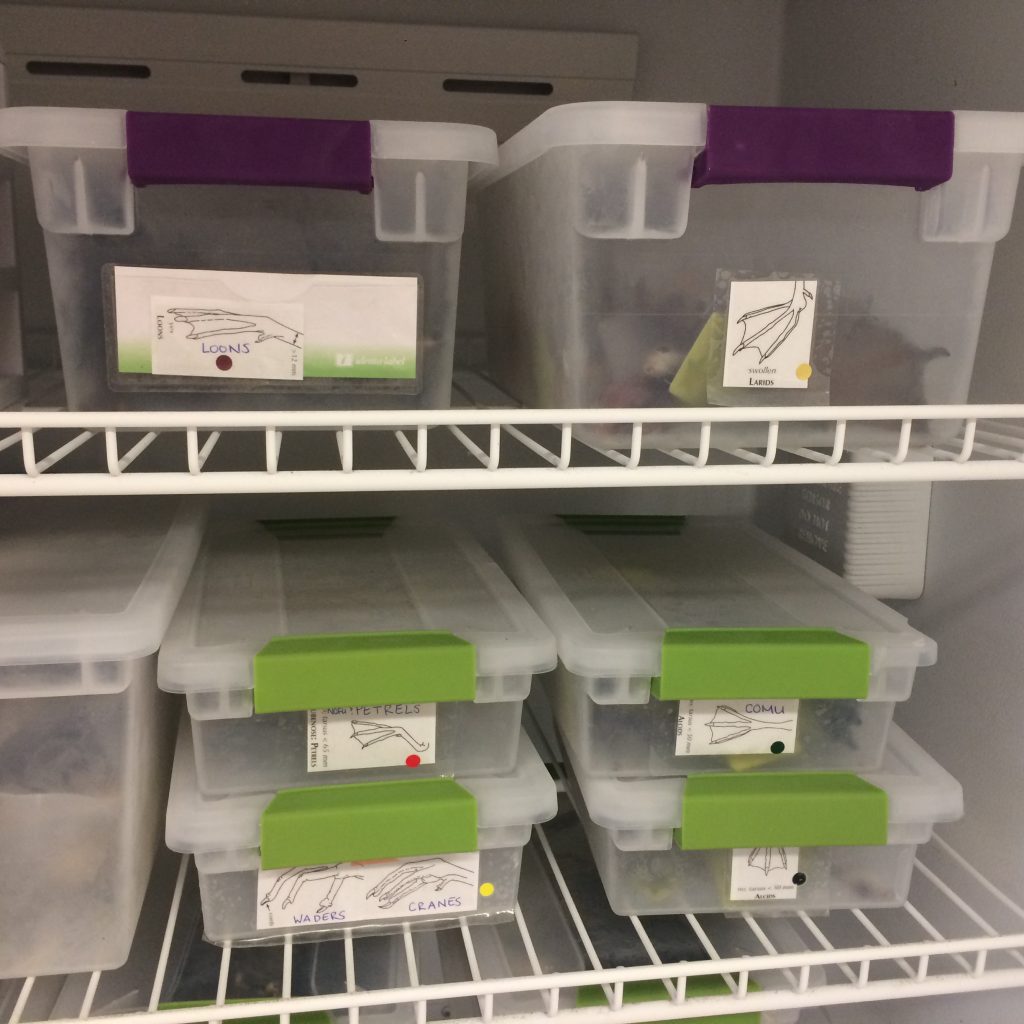

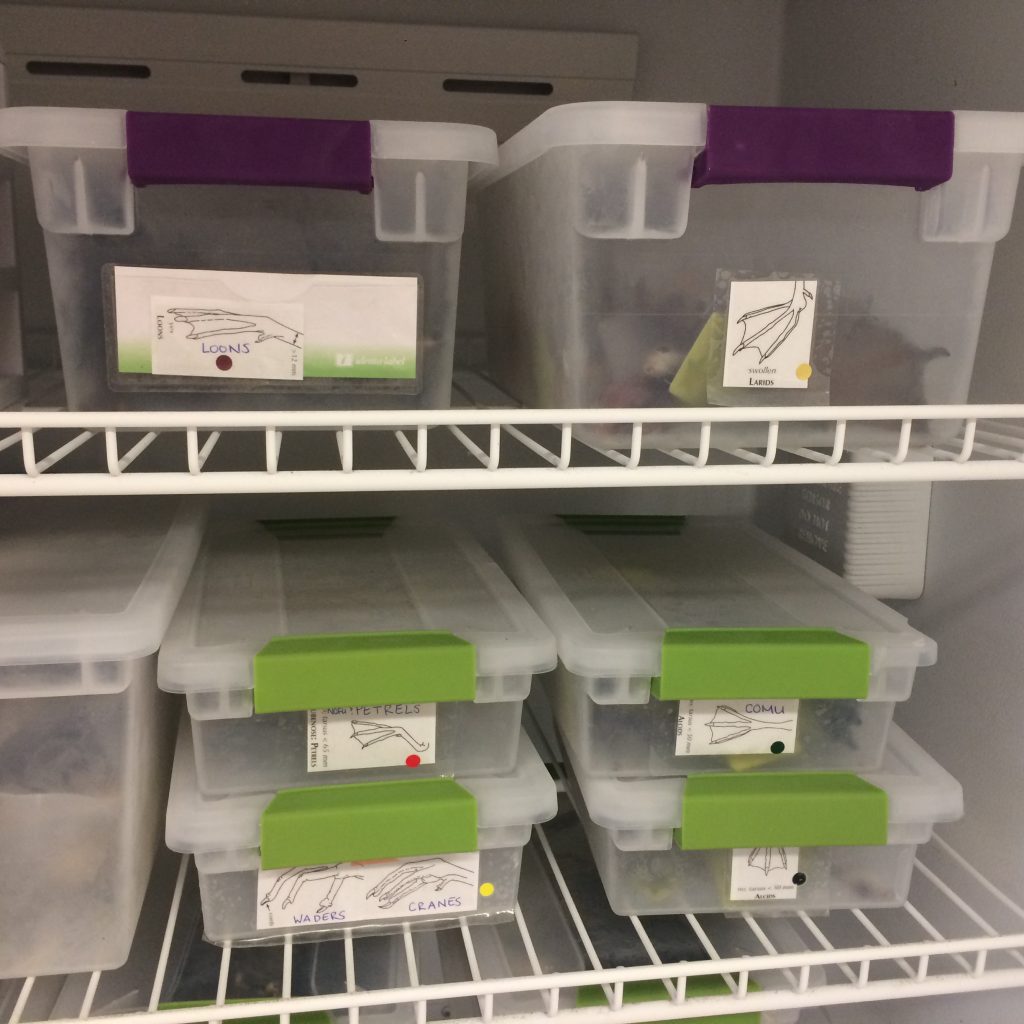

It was to get an answer to this question that I found myself not long ago in a basement lab of the UW Fisheries Science Building in Seattle with Hillary and Jackie Lindsey, COASST’s Volunteer Coordinator. When not in a plastic tub or suitcase, the bird teaching collection resides in two large freezers—a miniature natural history museum dedicated to the practice of using COASST’s field guide, Beached Birds. Inside the freezers are scads of small tubs, all of which are have labels with names like “COMU feet,” “Waterfowl: Diving Duck Feet,” and “Pouchbill feet,” among others. (There is also one called, memorably, “Heads” – remember bill measurement practice?)

The foot collection, organized by Foot Type Family, occupies a freezer in the COASST lab.

As any COASST volunteer knows, the teaching collection is central to their training. But teaching birds get handled and measured, frozen and thawed and frozen again on a regular basis, so their shelf life can be limited. Fresh specimens are needed at a fairly steady rate, and the collection needs to include the range of shapes, sizes and patterns encountered in Beached Birds. But COASST can’t simply repurpose carcasses that COASSTers find on their surveys. Permits are required from the relevant state and federal agencies. So are non-food freezers to keep specimens sufficiently cold. When certain species are scarce, COASSTers have occasionally been added to permits so that they can take on this above-and-beyond task, but COASST also has a network of contacts to whom they reach out. Happenstance rules the day—they can’t just ask the birds to fall out of the sky, Jackie points out—so mostly what comes back are Alcids and large immature gulls. That doesn’t mean there isn’t a wish list of a sort. “We’d really like a Pigeon Guillemot wing,” Jackie says, “but those are surprisingly hard to come by.” A useable specimen must be collected fresh and intact, after all, as if it did just fall out of the sky.

On this day, Hillary and Jackie are preparing several Common Murres that had washed up on the beaches of Seattle’s Discovery Park the previous October. With great precision, Hillary and Jackie remove the relevant parts: the wings at the shoulder, the feet just above the ankle joint so the tarsus can be accurately measured. The next step was adapted from processes used to prepare specimens at the Burke Museum of Natural History, a museum on the University of Washington campus that maintains the largest spread wing collection in the world. In fact, Ornithology Collections Manager Rob Faucett has mentored COASST staff and students in the practice of identification, preparation and care of specimens over the years. Hillary and Jackie take the wings and feet to a “setting station” (a large, flat piece of Styrofoam) and carefully position the specimens so that the tarsus and wing chord can be measured, and all the characteristics used in identification can be easily viewed–like number and shape of toes, and any pattern in the secondaries. The specimens will remain here for a few days to fix into these positions, before being labeled according to species and added to the appropriate Foot Type Family or upperwing pattern bins in the freezer.

Preparation of a Rhinoceros Auklet wing.

In addition to the murres, there are a few other specimens already laid out: a pair of Black-legged Kittiwake wings and feet collected by Hillary and her father while on a COASST training trip to the Long Beach Peninsula of Washington, a couple of Rhinoceros Auklets (Alcids) from the recent die-off off the Washington COASST, and two cormorant feet, one with a thick yellow band on it and the sequence JH8. The band catches my eye. I ask Hillary if she knows anything about it, if there was any information on the bird to which it belonged. “Whenever a banded bird comes to COASST (as a specimen or is reported on a datasheet) we enter the relevant information into the North American Bird Banding Laboratory database maintained by the USGS. If the researcher who banded the bird has entered the original banding data, it is shared with COASST and we wind up with a window into that bird’s life—I’ll check our records.”

A fresh Rhinoceros Auklet foot specimen (Foot Type Family: Alcids)

A day later Hillary sends me an email. The bird had been found deceased on a beach in Whatcom County, Washington in 2017, but had been banded four years earlier—in the spring of 2013 on the Oregon coast, Clatsop County. The bird was at least six years old. And now, almost dry, it’s feet were ready to take their place in a bin on a shelf in the freezer, to become objects of a different COASST fascination: examples of feet with four webbed toes.

Pinned into position so that all four webbed toes can be easily seen, this banded cormorant foot has a story to tell.

Reply below or email coasst@uw.edu with your guesses and suspicions. Thank you as always for sharing your expertise!

Reply below or email coasst@uw.edu with your guesses and suspicions. Thank you as always for sharing your expertise!