This post is the second in a series of three concerning the specific history of Barneston, Washington. The first one can be found here, at “A Brief History of Barneston,” and the third here, “Issei Life and Labor at Barneston.” This post draws upon material published in my 2017 article in Archaeology in Washington.

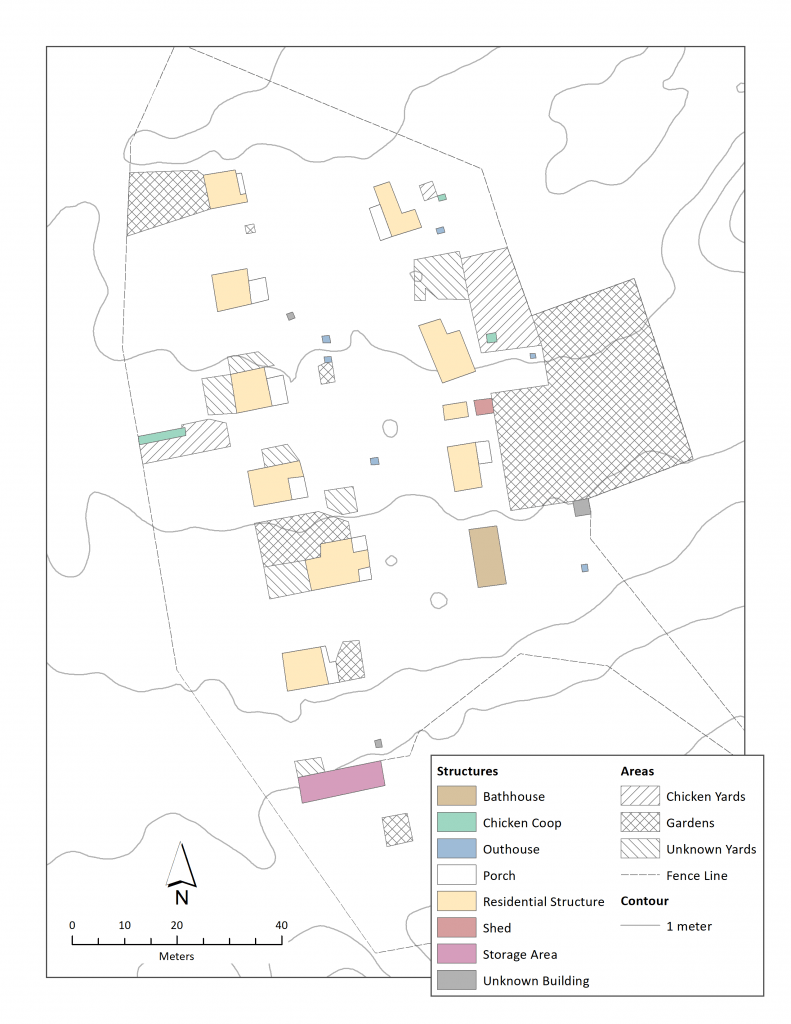

As with a number of other sawmill operations in the region, the Nikkei1 community (Figure 1) was spatially segregated from the other workers. Furthermore, and in contrast with the other inhabitants, both Issei bachelors and families lived in the same area. Most houses in the community measured between 15 and 20 feet on a side. There were 54 individuals identified as “Japanese” in the 1910 census, of which 43 were bachelors or married-but-living-alone and 11 were family members (3 families total; United States Bureau of the Census [U.S. Census] 1910). By 1920, the population had risen to 58, 17 of which were bachelors or married-but-living-alone, with the remaining 41 organized into 11 families. This increase in the number of families may have required the construction of additional households beyond the ones noted on our maps (Figure 2). The 1920 census also shows an additional population of 15 Issei railroad workers, however I am not yet sure if they actually lived at Barneston, or if they were merely there to be counted in Barneston’s census enumeration district (U.S. Census 1920).

Figure 1. Photograph of Issei community from the south, facing north. Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives.

There is some question as to the number and location of Nikkei camps in Barneston. An early cultural resource survey of the area suggested that the Japanese immigrants lived in two locations: one near–but not in–Barneston, and another further away in a location called “Hemlock” (Getz 1987:40–45). More recent heritage work found detailed survey maps which placed the Nikkei within the town of Barneston itself; oral testimonies gathered as part of this project showed no recognition of the name Hemlock (Brown and Schroeder 1996; Gilbert and Woodman 1995). The change in the community’s location—from outside of Barneston to the town proper—occurred sometime around 1906 or 1907 (Getz 1987). It resulted from erosion issues and concerns over possible pollution of a nearby river. I will write a bit more about this in a future post, but in effect, Barneston became entangled in wider debates about water quality and the watershed. This resulted in the Nikkei community not only being moved into the town, but also suffering some rather racist characterizations and attacks from local newspapers. Because it is better documented and less likely to have eroded, and because it was established right around the time of the first coordinated anti-exclusion efforts by regional Issei leadership, this project focuses on the camp within the town.

Figure 2. Nikkei community, as per 1911 R.H. Thompson survey map. Digitized and created by David Carlson.

Notes

1. I use the term “Nikkei” here to refer to the entire community. While the Issei are, for the moment, the primary focus of this project, the community included a number of Nissei children.