This post is the final one in a series of three concerning the specific history of Barneston, Washington. The first one can be found here, at “A Brief History of Barneston,” and the second here, “The Nikkei Community at Barneston.” This post draws upon material published in my 2017 article in Archaeology in Washington.

This project’s current knowledge of life and work at Barneston comes from a combination of oral testimonies and census data. The 1910 and 1920 federal censuses include occupational data, which provide some insights into the kinds of labor Issei did at Barneston (U.S. Census 1910, 1920). A synthesis of this data is presented on Tables 1 and 21. These tables are meant to be read left-to-right, row by row. The data reflect a broader industry trend towards hiring Issei largely as general labor (Dubrow et al. 2002; Olson 1927). A more detailed look shows that, while this trend plays out in both 1910 and 1920, it may have been more severe in the later period. Occupations listed on the 1910 census consist of: boarding house operator, driver, grader, planerman, sawyer, trucker, and general laborer (in either the sawmill or planing mill). The 1920 census shows a drop in the diversity of listed occupations, with only general laborer, foreman, and cook represented.

I am still reconstructing what each of these positions may have entailed, but based on a 1972 U.S. Department of the Army (U.S. Army) technical manual on logging and sawmill operation, this shift may represent a loss of responsibility and access to skilled positions for the Issei, possibly in response to rising anti-Japanese hysteria after World War I. Graders, for example, were in charge of classifying the quality of the lumber produced, and sawyers were responsible for the proper operation of sawmill machinery (U.S. Army 1972:Glossary 5). The technical manual remarks that “quality and quantity of lumber sawed depends on [the sawyer’s] judgement, skill, and speed” (U.S. Army 1972:Glossary 10). This does not seem to be the result of any change in how the census is gathered, as an even more diverse array of jobs—including sawyer and grader—are recorded for non-Japanese workers of both periods. The absence of Issei in such positions in 1920, then, may represent the a more severe example of the differential hiring practices already present in 1910.

| Table 1. Proportions of workers at Barneston by occupational category and region of birth – 1910 | ||||

| Occupational Category1 | Japan | U.S. | Europe2 | Other |

| Engineering and Repair | 44% | 56% | ||

| General Labor | 83% | 7% | 10% | |

| Managerial | 100% | |||

| Specific Labor | 45% | 30% | 20% | 5% |

| Other | 100% | |||

| Unknown | 29% | 29% | 42% | |

| Table 2. Proportions of workers at Barneston by occupational category and region of birth – 1920 | ||||

| Occupational Category1 | Japan | U.S. | Europe2 | Other |

| Engineering and Repair | 57% | 36% | 7% | |

| General Labor | 69.5% | 18.5% | 6% | 6% |

| Managerial | 33% | 67% | ||

| Specific Labor | 61% | 32% | 7% | |

| Other | 11% | 67% | 11% | 11% |

| Unknown | 50% | 25% | 25% | |

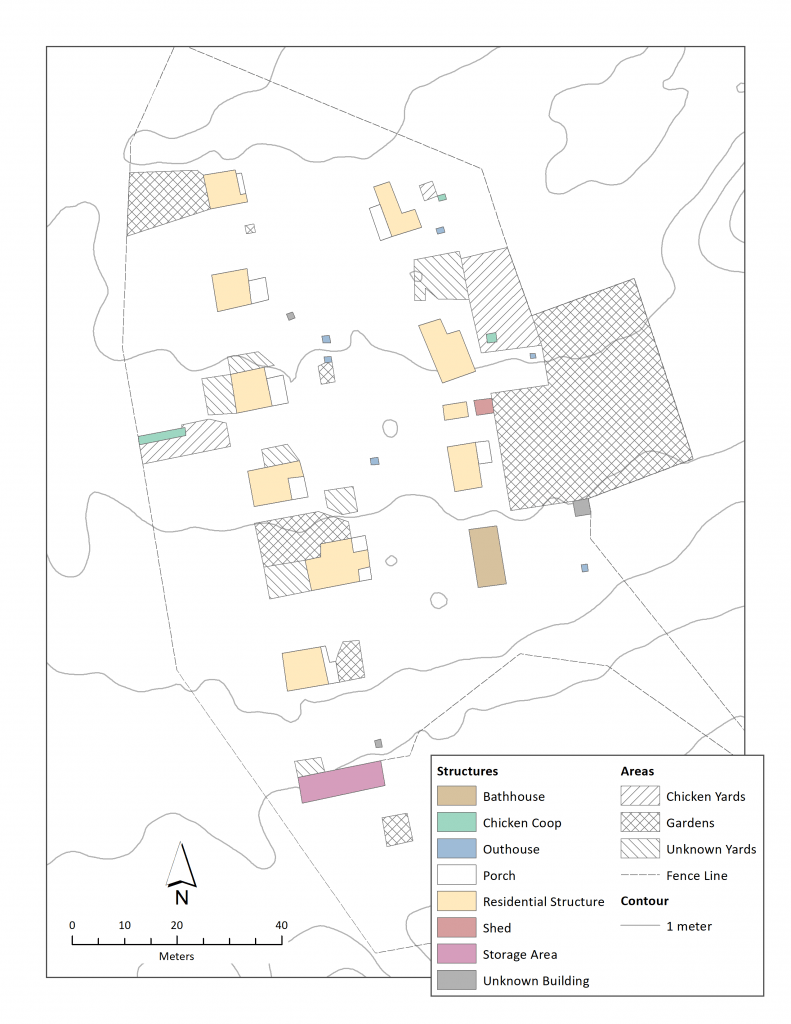

The remaining current knowledge of the lives of these immigrants is based heavily on oral testimonies collected by University of Washington students in the 1990s (Brown and Schroeder 1996; Gilbert and Woodman 1995). These suggest that most of the buildings in the Nikkei community were occupied by four single men. The rest were occupied by families, who occasionally built small extensions of their houses for new family members (with company permission). The bathhouse in the southwest camp was an important corporate structure; communal bathing has strong cultural significance in Japan, and the bathhouse operated in a traditional manner, with men bathing before women and children. Informants also report that they used the local town store only occasionally, preferring instead to either to go Nikkei shops in Seattle or order food from East Asian-owned companies that made monthly deliveries to the site. Many supplies were ordered cooperatively, including food, which was cooked by an Issei cook working out of the bathhouse, though I am not yet sure if she cooked solely for the bachelors or also assisted the families. These economic connections, plus the fact that Seattle was the port through which most Issei immigrants came, produced strong ties between Barneston and the Seattle Nikkei community (Brown and Schroeder 1996; Gilbert and Woodman 1995).

Notes

1. Occupational categories were created to simply the very diverse array of jobs reported on the U.S. Census. Sawmill operations involve a considerable number of specialized roles, and I have tried to condense these roles as best as possible to illustrate the disparities in hiring and labor among various racial and ethnic groups. Engineering and Repair refers to occupations tasked with the maintenance of the mill (e.g. engineers, millwrights). Managerial are those who have some managerial control over mill operations (e.g. supervisors, foremen). Specific Labor refers to those whose census entry indicated that they performed some specific role in mill operations, such as graders (who graded the quality of the wood) or sawyers (key personnel who ensured that the wood was cut appropriately). General labor refers to those listed as “laborer”, who had no specific task associated with them. Other refers to other occupations (e.g. cook), and unknown to those occupations I could not comfortably classify or for those census entries I could not decipher.

2. “Europe” covers a very broad area, and there’s evidence that the people who operated sawmill towns treated (or would have liked to treat) different groups of Europeans differently (Beda 2014; Carlson 2017). Northern Europeans, for example, were valued for their skill (since the immigrants coming over from Northern Europe often had experience in their own countries’ lumber industries), but were also seen as more likely to be union-friendly. Despite this, I have combined all of Europe together to simplify the table and highlight the degree of labor segregation on the towns.