If you haven’t had the chance to do so, you may want to read our previous posts on “Push” versus “Pull” factors in immigration, the impetus for Japanese immigration, and the economic reasons for working on sawmill towns. This post draws upon material published in my 2017 article in Archaeology in Washington.

In a previous post, I wrote a bit about some of the economic factors that may have encouraged Issei to come to towns. Here, I would like to explore some of the non-economic reasons for working on a mill town. As before, this material is a synthesis of published literature and oral testimonies regarding Issei on sawmill towns.

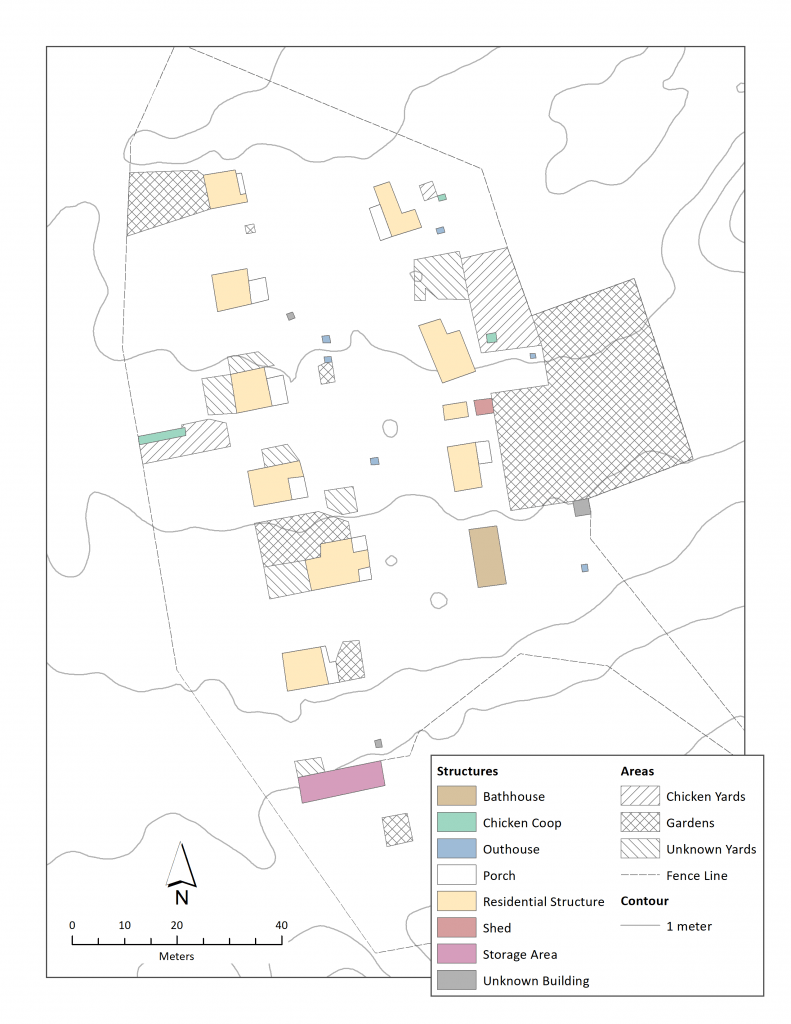

The non-economic factors motivating Issei to work at sawmill towns appear to be the availability of “amenities”. Issei sawmill communities organized and ran an array of amenities and social networks to meet their psychological, social, subsistence, and cultural needs. As a number of testimonies suggest, these likely served as an additional draw for the Issei, particularly those with families. These amenities varied from town to town. Barneston possessed only a store, a school, and a bathhouse, while nearby Selleck had much more, including a movie theater (Bowden and Larson 1997; Brown and Schroeder 1996; Dubrow et al. 2002; Gilbert and Woodman 1995). While some amenities were likely provided by the companies which owned the towns, the workers were largely on their own. Logging and sawmill companies were aware of the paternalistic and corporate welfare policies in other industries. However, the economic geography of logging and wood production, in combination with company stinginess, meant that these philosophies by and large do not appear to have taken hold in the lumber industry (Beda 2014:84-110; Carlson 2003; Ficken 1987; see McClelland 1998 for an exception).

Figure 1. Advertisement for the M. Furuya Company from a 1919 edition of the Four L Lumber News. Companies like this served towns like Barneston.

As a result, workers were frequently responsible for their own amenities. For the Japanese, this meant establishing a number of social services within their communities, in addition to taking advantage of those already present. It also meant establishing wider, regional social and economic connections between Japanese communities in company towns and in urban areas, such as Seattle. In terms of daily subsistence, Issei (and, more broadly, Nikkei) sawmill communities relied heavily on urban-based companies to meet their cultural and culinary needs (Figure 1), though this may have been different for communities based in ports. Representatives of various Asian food and market companies made monthly visits to the town of Barneston to drop off supplies. Barneston’s Issei often purchased these supplies communally (Brown and Schroeder 1996; Gilbert and Woodman 1995). Similar practices occurred at sawmill towns like Manley-Moore, Selleck, and National (Bowden and Larson 1997; Dubrow et al. 2002; Hall 1980; Olson 1924a). Finally, like their European-American and European counterparts, Issei supplemented their diet whenever possible with gathered and home-grown vegetables and fruits. They also raised chickens and on occasion hunted deer (Beda 2014; Ito 1973:410–412, 415–416).

These hunting and gathering activities deserve special consideration, as they speak to the kinds of labor benefits that family members could bring to the towns. Gardens, for example, served as an important means of subsistence, as they allowed Issei (and their non-Japanese counterparts) access to a renewable source of fresh vegetables and fruits. Gardens could be quite complex; one young adult who worked at Barneston in its latter years recalls the presence of not only gardens but fruit trees, including apple trees (Brown and Schroeder 1996). The inhabitants of Selleck routinely gathered apples from the trees of a nearby abandoned orchard (Bowden and Larson 1997). Families may have been particularly well suited to take advantage of these opportunities; women (and children, when they were not in school) could have tended gardens and gather local resources, in addition to maintaining the household (Brown and Schroeder 1996; Ito 1973:190). Of course, not all women were limited to these activities; some maintained jobs that provided additional sources of income for the family.

Figure 2. Schoolhouse at Barneston. Courtesy of Seattle Municipal Archives.

Another important non-economic draw for families was education. Multiple informants report either attending school as children in these towns or sending their children to schools. Schoolhouses were also used by adult Issei to take night classes in the English language (Olson 1924a, 1924b, 1924c). Schooling was important enough to Nikkei families that if a school in a town closed, they would seek alternative means of education. In the case of Barneston (Figure 2), the closing of the town school in 1920 led to some children having to walk two hours a day to the school in Selleck. Other families simply left town, finding other mills where the parents and older siblings woulc work while younger siblings attended public school (Brown and Schroeder 1996). Schools were generally not segregated, and so the local school often served as a point of contact between Issei and non-Japanese families. And while American schools typically did not teach much on Japanese culture or language, Issei communities managed to meet this need by offering their own night classes. Children in sawmill towns often spent the day in public school and the night being schooled in Japanese language and customs by local, knowledgeable laborers (Bowden and Larson 1997).

Additional References*

*See the Common References page for a full list.

McClelland, John M.

1998 R.A. Long’s Planned City: The Story of Longview. Westmedia Corporation, Longview, Washington.