When watching Barbara Loden’s Wanda, it’s hard to imagine how this film is even remotely considered feminist. The main character, Wanda Goronsky, modeled after Barbara Loden herself, seems to refuse to stand up for herself or take control of her situation. The audience watches as she gets pushed around by other people, while Wanda herself seems contentedly resigned to the various situations she finds herself in. In truth, Loden’s Wanda had done something that no other film had really done before; it was a tribute to the untold story, the marginalized woman. Not the untold story of the marginalized woman became strong and outspoken and stopped taking crap from men, but the unspoken story of the marginalized woman who couldn’t stand up for herself. Such stories are as equally important as the former.

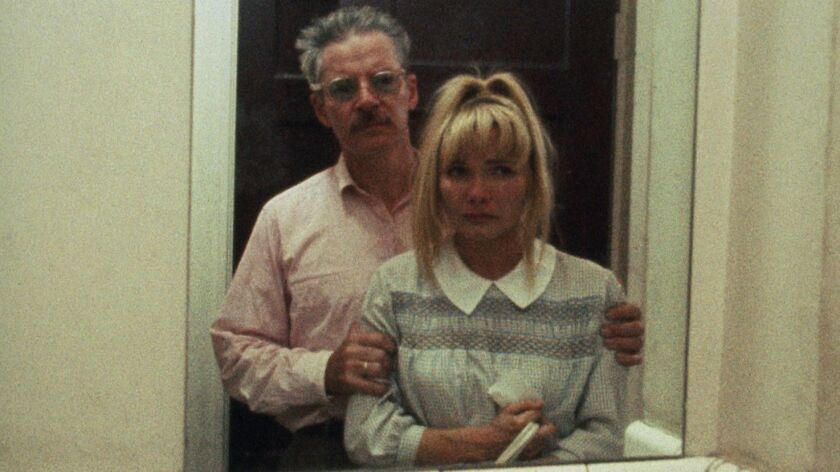

Wanda follows its titular character with her signature top ponytail and handbag. The film starts with Wanda getting divorced, and when asked by the judge if she has any defense for herself for her children’s sake, Wanda doesn’t even try to protest. In a shocking demonstration of meekness, she just admits that her children would be better off with her ex-husband and leaves the courtroom. Afterwards, by chance, Wanda then wanders into the plots of a fugitive bank robber, Mr. Dennis, who takes her along with him and makes her his accomplice. The two share a tumultuous relationship as they go about planning and executing their next heist.

The audience sees Wanda in an almost permanently light of being put down by others around her; There isn’t anyone who has a kind or respectful word for her. She is used, berated, slapped, dismissed, and yet, Wanda doesn’t even seem remotely sorry for herself or her situation. She is remarkably detached, and once can hypothesize that perhaps control is never something that she desired for herself, in which case, what does that say about her situation? Can a woman with no desire to be in control of her situation be oppressed? Of course, Wanda’s desires, or lack thereof, can easily be attributed to internalized marginalization by society, and she is perhaps not as desire-less as she may seem; the repeated motif of Wanda checking her empty wallet, her treasured possession from her past life, seems to imply that she is looking for safety or security. Even so, during the whole movie, her persona shines through the negativity. She is comfortably chatty with the man who is forcing her to rob banks with him, she ties her hair up and does her makeup every day as if everything is normal, and she happily eats a meal with Mr. Dennis as if they were on a date. These are not the traits of a woman in distress, but perhaps a woman who’s passively content with nothing and being nothing.

Wanda premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 1970, where it won the Critic’s Prize. It’s commercial release was met with critical acclaim in a few newspapers, but fizzled out quickly and quietly into nothing. The movie itself was exactly like Wanda, honest and genuine, destined to be forgotten and overlooked. Not only that, but Loden herself seemed to be living Wanda’s life. Loden’s second husband, Elia Kazan, was easily as abusive and horrible as the men in the film. From refusing to acknowledge his wife’s directorial independence, to interfering with her acting career, to going so far as to claim credit for Wanda after Loden’s death at 48 from cancer, Kazan is as easily a metaphor for Mr. Dennis as Loden is for Wanda.

In the end, Wanda sheds light on an important subgroup of people: the marginalized women who don’t have the luxury of feminism. We so often cheer at the depiction of a woman who gloriously breaks free of her patriarchal bonds of domesticity, but in reality, that’s just not the complete truth. Though at the end, there is an implied change of Wanda’s heart, Wanda tells the candid story of a woman who is beaten, but hasn’t lost. It’s hard to come away from such a negative film with a sense of hope, but perhaps Wanda is one of the woman referred to in Margaret Thatcher’s famous quote, “Well-behaved women seldom make history.” Wanda is a call to us to remember the women who have and will fall into obscurity because of a society that will not value them.

4/5 STARS