Hayao Miyazaki. His Wikipedia article may not state it, but he has produced more than enough masterpieces to be unofficially acknowledged as the “godfather of animation.” Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, My Neighbor Totoro, and Princess Mononoke are all of the spectacular stories which he has beautifully hand-animated with his collaborators at Studio Ghibli. However, Porco Rosso also deserves to be recognized in his upper-tier of films.

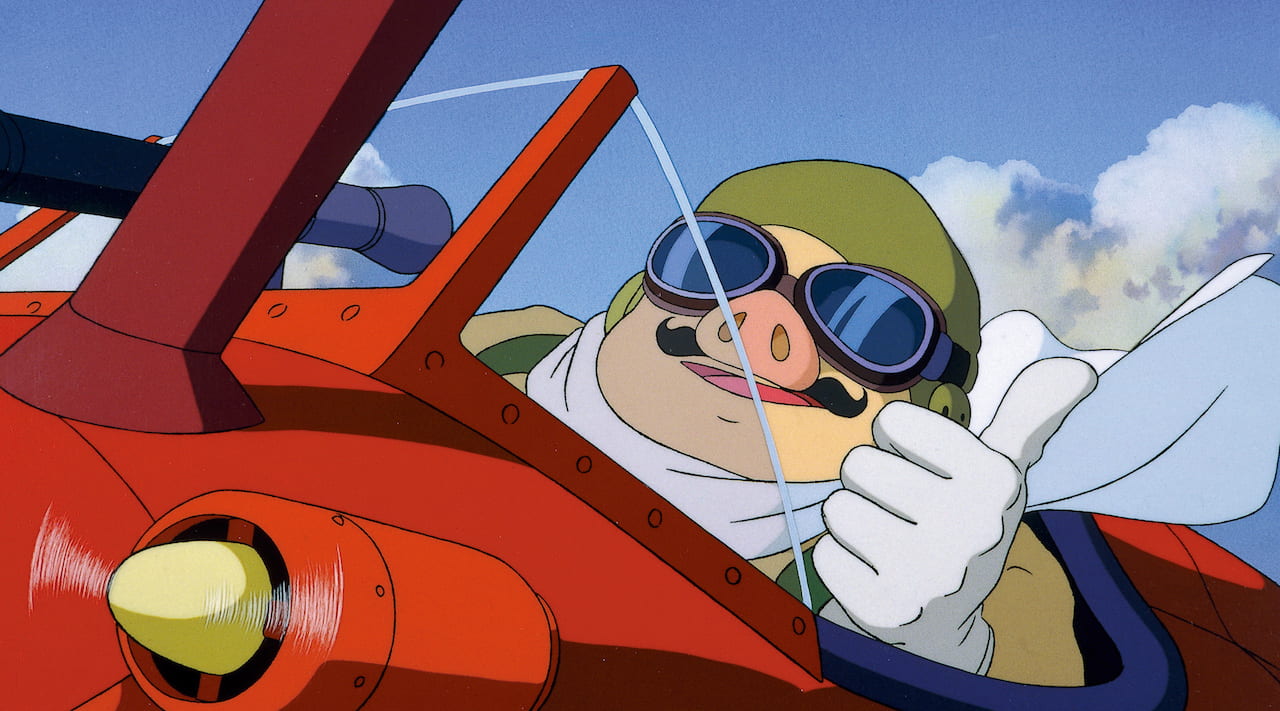

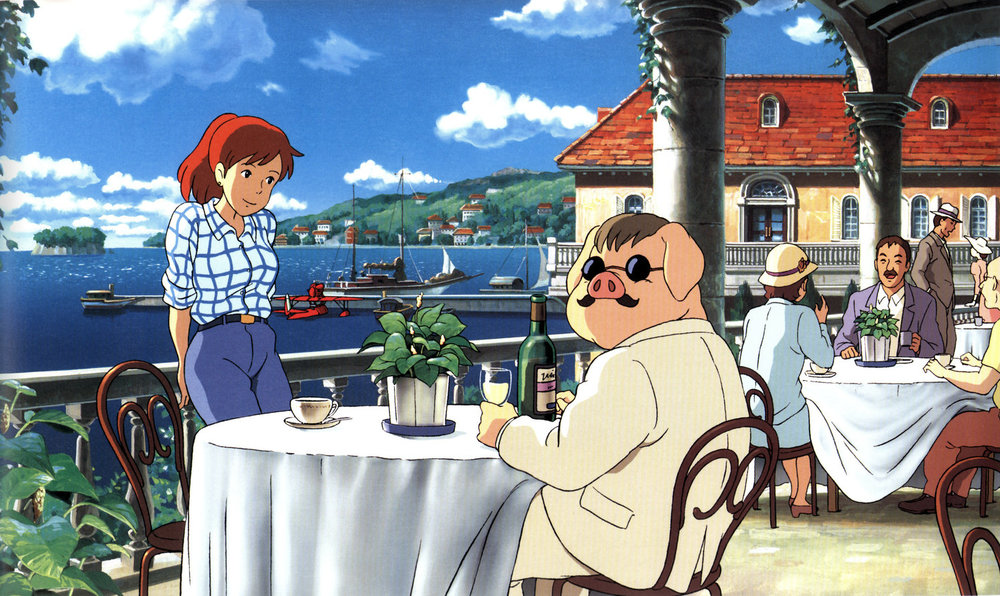

In contrast to the wonderful, imaginative worlds of Miyazaki’s filmography, Porco Rosso is a period film set in a definite area. In the skies of fascist Italy in the 1930s, the film chronicles the adventures of its namesake character, who, while being a fighter pilot for Italy during World War I, was mysteriously turned into a pig. During these adventures, he is constantly chased by Curtis, an almost-arrogant American pilot, and his crew, as well as the Italian authorities while meeting Fio, an aviation-engineering apprentice of a long-time of his mechanic.

Porco Rosso may be one of the most fascinating characters in the context of Miyazaki’s filmography. He is cool and quiet, rarely does the audience see him in a panic. As a loner, Porco does not realize romantic interests towards him. Rather, much like a classic cowboy in an American western, he travels loosely across the skies. He fights with confidence in his abilities; however, the depth comes in understanding that it comes from a traumatic past. It is clear that his reserved nature shows his hesitancy to connect with others. It is a theme that can be seen in many, many, many war films. To see it manifest in a film designed, in part, to awe children, highlights the beauty in Miyazaki’s faith in the youth.

Contrasted with American animation, which uses bodily-fluid jokes as a primary tool to elicit laughter from young children, Miyazaki uses much more mature humor to make us laugh. Aside from some of the wonderful one-liners, Porco delivers in the face of conflict, the satire is used as the crux of entertainment, especially in the last act. When Curtis and Porco ultimately duel to see who is “the better man,” the fight stalls when both their planes are equally badly damaged. They step out and proceed to get into a fistfight. A fistfight. In a film supposedly interested in dogfights, our protagonist and antagonist go mano-a-mano in a very weird, brutal, and physical fight.

With every pause after a swing, Curtis and Porco discuss their emotional resentment of one another: namely, they each think they are womanizers. Watching them have an almost therapeutic conversation about their romantic insecurities while beating each other tells the audience what the story is about: manhood. What does it mean to be a man? It can often be idolized as a macho attitude: quick to act, slow to think. Men fight honorably, they engage in violence, they stay cool. It is the element audiences have come to identify with as the reason John Wayne is so enigmatic in his Western roles. Yet, Miyazaki makes viewers laugh at the ridiculous, almost anti-climactic ending. It brilliantly subverts the glorification of violence; a sentiment no stranger to Myizaki’s anti-war stance in his films.

The hot temper we have come to associate with men, in this film, is resolved by women. For instance, when Curtis ambushes Porco, it is Fio who ultimately strikes a bargain between the parties. However, this is specifically because of Curtis’ immediate romantic interest. An interest that reeks of desperation and emotional immaturity. The violent shell is peeled and we see the performative aspect of masculinity.

While on the surface Miyazki seems to be brushing off his political science degree to condemn fascism, on a deeper level, this film is a critique about how men hide behind masculinity. The beauty of this film is that it does not work. The power is, through the form, style, and humor, this message reaches all ages. This film was initially billed as a short film that would screen on Japan Airlines. This is the reason why the film’s opening title cards are in numerous languages. But it also signifies the deep, realistic themes of masculinity. Is this too deep of a reading? Maybe. But regardless, it remains a highly interesting watch.

5/5 STARS