Our group of UW and Hoonah “pullers” preparing to paddle out of Port Frederick in Hoonah. Back (L-R): Sherry Mills and Zach Inglesby of Hoonah, Marco Ammatelli, Natalie Schwartz, Shawna Marbourg, MacKenzie Price, Calvin Smith, Owen Oliver, and Bambi Jacks of Hoonah. Front Row (L-R): Owen James of Hoonah, Maddie Joy, Tim Billo, Abby Weiler, Jayna Milan. Photo by Don Starbard. We are deeply indebted to the community of Hoonah for hosting us, sharing their stories, and offering us key insights into the issues we came to explore on this course.

By Tim Billo (Faculty, University of Washington, Program on the Environment)

“[Glacier Bay National Park] was founded in the spirit of John Muir, with a strong tradition of scientific inquiry [and] an historic focus looking only as far back as the arrival of European explorers. Perhaps it was this short-sightedness that led to many of the conflicts to come.”

–Wayne Howell, 1998

“We lived in that area. If you’ve been there you’ll never forget your visit to Glacier Bay. The most beautiful place you’ll ever visit. The best hunting grounds, the best fishing grounds…”

–Bill Wilson, Jr., Hoonah, 2018

“The first day I arrive, it feels like the ancestors putting their arms around me…we live our culture. We are not just in museums. We are not just in those old stories. We are here, the original descendants of the people that once lived in Glacier Bay…”

–Bertha Franulovich, Alaska Native Voices interpreter, Glacier Bay National Park

This blog documents an extraordinary journey of learning, adventure, and friendship along the northwest coast, in a place which is in some ways, not that far from Seattle. From July 30 to August 13, 2018, our University of Washington Environmental Studies course dove deep into the culture and natural history of southeast Alaska, as we witnessed new history being made between the National Park Service and the Huna Tlingit. Each student has written about one or more days of the course, and provided reflections on what the experience meant to them. It has been our goal here to accurately summarize our impressions and learning, in order to share our experiences with a wider audience. While we have consulted our partners in Alaska before posting, I take responsibility for any omissions and/or misrepresentations that might inadvertently have occurred throughout these posts. These are our impressions and memories only, and should not be taken as the authoritative source of information on any of the people or issues described. I invite anyone with questions, concerns, or comments to contact me at timbillo@uw.edu, or, to contact our partners in Alaska directly for more authoritative information.

During the backcountry portion of the course, we brought along many readings tied to the landscape of the region, including several volumes of poetry by Tlingit poet, Nora Marks Dauenhauer. Her words inspired us on our journey, and we’ve featured her poetry at the head of some of the posts.

—

If you are interested in a longer explanation of how this course came to be, you can read about it here. Otherwise I want to move straight to an overview of the course, including essential background to the topics we covered, and acknowledgements of the various people that contributed to our learning.

First and foremost, it is essential to understand that the Huna Tlingit people lived in Glacier Bay prior to the glacial advances associated with the Little Ice Age 500 years ago. The Little Ice Age glaciers descended rapidly from the Fairweather Range (at the speed of a running dog, according to a story by a tribal elder, Amy Marvin), forcing them out of the bay they called Sit’ Eeti Geeyi to other locations around Icy Strait, including the town which would come to be known as Hoonah (or Xunaaa—loosely translated to “in the lee of the north winds”). The events surrounding this relocation are documented in tribal stories which have been passed down over many generations. Famously, John Muir visited the area a handful of times, beginning in 1879, making stops in Hoonah and recruiting Hoonah Native guides in Berg Bay (a bay within Glacier Bay that had been re-occupied as a seasonal base for hunting seals after glaciers had begun to retreat north up Glacier Bay again starting in the 1800s). Muir’s visits and subsequent writings quickly heralded a new era of tourism and scientific study in Glacier Bay, and the eventual establishment of a national monument (1925) and later a national park (1980). The monument and park would, by law, remove the Tlingit yet again from Glacier Bay, effectively suppressing subsistence hunting and gathering activities. The early years of the monument came at a time when the Bureau of Indian Affairs was, as a matter of official policy, was attempting to strip Native Americans across the country of their language and culture. With respect to land management in the Huna Tlingit homeland, these factors together led to decades of distrust, misunderstandings, and entirely justifiable anger on the part of the Huna Tlingit towards the federal government broadly, but also towards park rangers who (although sometimes well-meaning people) were following orders from Washignton, D.C. and Sitka (the former base for Glacier Bay rangers) with little understanding of the Huna Tlingit situation.

Around 1998, during my first visit to Glacier Bay, Wayne Howell and Mary Beth Moss, both Glacier Bay National Park anthropologists, were in the throes of initiating what would become a 20+ year effort on the part of Glacier Bay National Park, to restore ties with Native communities, with the goal of ameliorating infringement on Native sovereignty and subsistence rights in Glacier Bay National Park. These efforts reached a zenith on August 25, 2016 when, as part of Glacier Bay National Park’s celebration of the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service (NPS), the Huna Tlingit paddled their canoes into Bartlett Cove to occupy their new tribal house (Xunaa Shuka Hit, loosely translated as Huna Ancestor’s House, and usually referred to simply as the Huna Tribal House), a tangible footprint in Bartlett Cove, marking the return of the Huna Tlingit to their homeland in partnership with the federal government in the cooperative management of their traditional territory. [Tribal Administrator Bob Starbard, would later emphasize to me that the ceremony was co-hosted equally by the NPS and Hoonah Indian Association (HIA) and that HIA had led the way in selecting August 25th, fully mindful of the symbolism in their appropriation the NPS Centenary date, and their transformation of this date into the official date of reclamation of their homeland in Glacier Bay].

In front of Xunaa Shuka Hit, with Sally Jewell, center. The “Huna Ancestor’s House” was one of the most beautiful buildings I have ever been in. Every bit as exquisite as I had imagined, and then some. Two years after its dedication, the aroma of cedar inside is still strong. Symbolic artwork, telling the stories of the Huna Tlingit clans, adorns the walls and posts inside the building. All of the artwork and planks were shaped by hand–or more accurately, by adzes wielded by carvers we would come to know personally–Gordon Green, Herb Sheakley, and Owen James–over a period of 8 years. When they began the project, there was not even funding for the house–but there was a promise that the house would be big enough to house whatever they carved–so they went big! Everyone we met who had been at the dedication ceremony on August 25, 2016, described the way the walls pulsed like a heartbeat with the music and dancing, as if the house were literally coming to life.

Bill Wilson, Jr., one of a dwindling number of fluent speakers of the Tlingit language, along with an intergenerational cross section of the community, welcomes us to Hoonah with ceremonial storytelling and song.

Thus, we came to study the history and current state of cultural revival on the part of the Huna Tlingit, and more specifically, the evolution of the relationship between the Huna Tlingit and National Park Service. We came to study the reconciliation process; the events leading up to the establishment and occupation of Xunaa Shuka Hit in 2016, and further progress symbolized by the raising this summer of a healing pole in Bartlett Cove. We wanted to meet and understand the people who made this reconciliation possible, and think about the future of this unique collaboration, which can serve as a model for other national parks around our country. Management of wilderness spaces in the region is not just the responsibility of the National Park Service, however. Much of the land around Hoonah is owned by the US Forest Service, Huna Totem (Hoonah’s native corporation), and Sealaska (the regional native corporation). We came to understand the unique arrangements of ANCSA and ANILCA, which make the Alaska Native situation (and indeed the general management of wilderness spaces in Alaska with respect to all Alaskans), so different from the situation of tribes and landscape management in the Lower 48. We also came to explore the Huna Tlingit homeland (Sit’ Eeti Geeyi, or “Bay Taking the Place of the Glacier”) on its own terms, through an 8-day kayak camping trip into Sit’ Eeti Geeyi or Glacier Bay. We wanted to understand for ourselves what value there is in that elusive idea of wilderness, as conceived and championed by John Muir, an idea which invokes many interpretations and continues to inspire so many “tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people”, but which is usually framed as being at odds with those who would connect with the landscape for subsistence purposes.

One of many deep conversations around a fire, here some 30 miles of paddling into the wilderness of Sit’ Eeti Geeyi, the Huna Tlingit homeland in Glacier Bay National Park. During the course, each student took turns leading a discussion on a topic of their choosing, relating to course themes. Topics included ANILCA and subsistence by Alaska Natives and other Alaskans in wilderness, modern re-interpretation and appropriation of Tlingit art, access or exclusion from wilderness recreation and the role of the outdoor clothing industry in promoting or breaking down stereotypes, balancing subsistence harvest and preservation in Glacier Bay, wilderness and the cruise ship industry in Glacier Bay, and more.

With respect to Glacier Bay, we were interested in whether there are any grounds for common understanding between the National Park Service and the Huna Tlingit, across that cultural chasm and the hurt of forced exclusion. Can the preservation mandate of the National Park Service co-exist with the cultural, spiritual, and practical needs for subsistence hunting of the Huna Tlingit in what is rightfully their homeland? Who has the right to profit from tourism in the national park, and to explain the history of “place” to tourists? These are some of the many questions we wrestled with, and that are part of a broader discussion between the Huna Tlingit and the National Park Service. While Xunaa Shuka Hit is probably the biggest achievement to date, it is significant that half of the educational programs at Bartlett Cove, as well as on ships entering the park, are now done by Native interpreters in a cooperative agreement with the National Park Service. National Park Service rangers (unless they are Huna Tlingit and sanctioned by Hoonah Indian Association) are not allowed to brief visitors on the historical relationship between the Tlingit and the NPS, nor can they interpret the artwork at Xunaa Shuka Hit, as those are not their stories to tell (similarly, HIA cultural interpreters can only tell the stories of their personal clan). There are currently experimental spruce root and gull egg harvests underway in Glacier Bay, not because they make economic sense for the Huna Tlingit people, but because they make cultural sense, and are symbolic of shared sovereignty over the land. There is also debate over whether traditional seal harvest could occur again in the future.

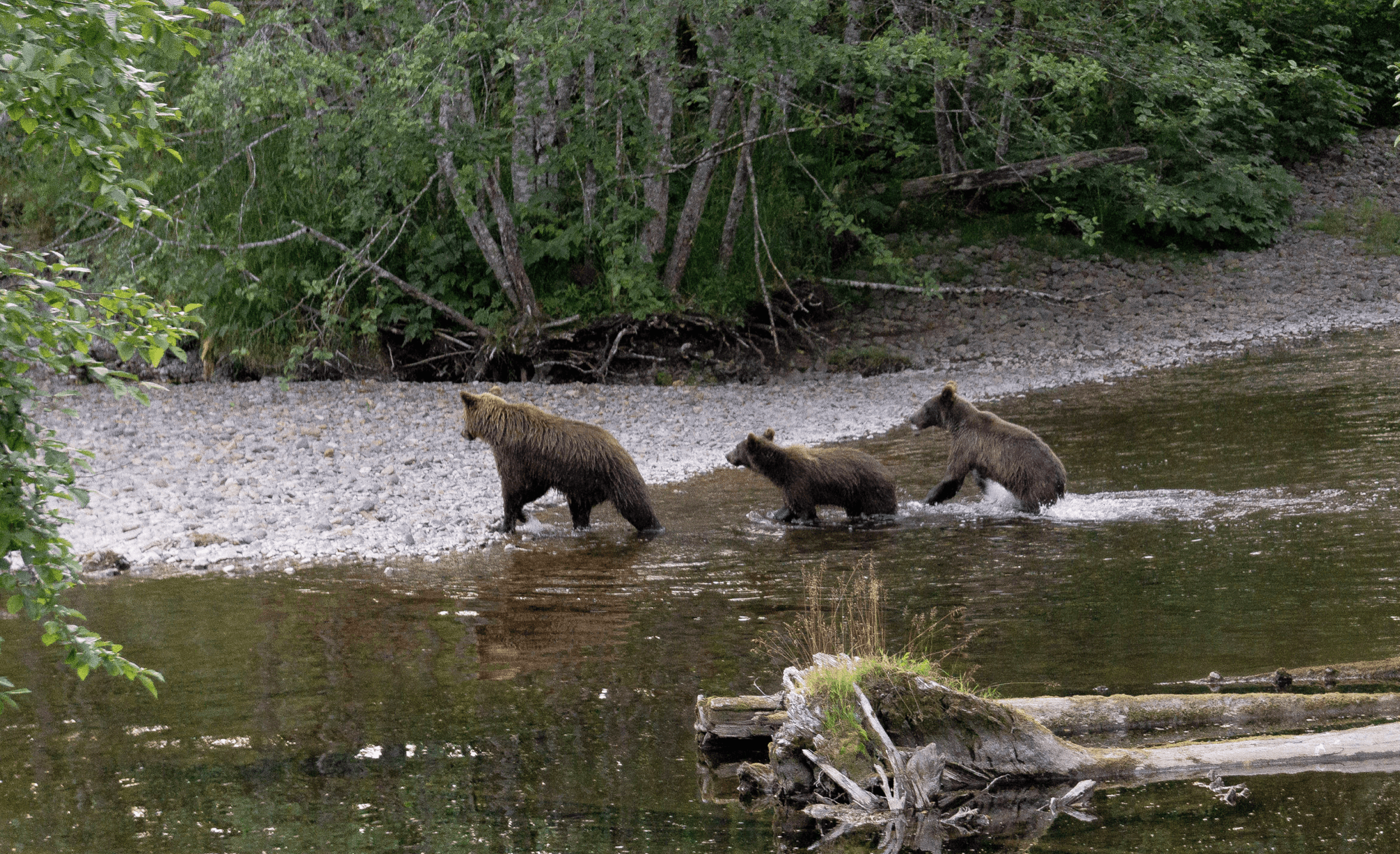

The Hoonah Indian Association (HIA), the federally recognized tribal government under which the Hoonah Tlingit clans are organized, shares the conservation mission of the National Park Service. The right balance of symbolic subsistence, together with preservation of the landscape and resources of Glacier Bay, must be worked out in joint leadership between the national park and the HIA. The successful raising of the healing pole two weeks ago increase the chances that that balance will be achieved and sustained into the future. Glacier Bay National Park is a richer place for the presence of the Huna Tlingit. The Huna Tlingit, perhaps better than anyone, understand the long arc of time, and the resilience of people and nature when that human/nature relationship is properly tended. As a matter of official policy, the HIA also recognizes that anthropogenic climate change presents challenges unlike what we have encountered in the past, and are fully on board with the need to consult science, both on climate change and sustainable harvest levels when it comes to subsistence. As a subsistence culture, the Huna Tlingit understand first hand climate change as a real threat to their culture and livelihood in their ancestral homeland. We found this to be a frequent topic of current conversation and historical storytelling.

Taking a break in our discussion at Xunaa Shuka Hit. Former Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell talks with student Natalie Schwartz, while Superintendent Philip Hooge, and Tribal Administrator Bob Starbard listen.

We are indebted to many people for making this course what it was. First and foremost, I want to thank Bob Starbard, Tribal Administrator of the HIA, for inviting us and hosting us in Hoonah to help us understand the present economical and psychological position of the Huna Tlingit, and for rightfully reminding me that the HIA is the “sole entity that officially speaks to the nature and state of the relationship (past, present, and future) between the tribal community and the NPS.” The course would really not have been what it was, without this essential time in Hoonah. Several subsequent posts articulate Bob’s perspectives, but briefly, in Bob’s words, the tribe has moved from a place of “ishaan” (Tlingit for self pity) to a place of agency. He is comfortable with asking for a “hand up” every now and again, and seeking out collaborations, but the HIA will no longer settle for “hand outs”. That is, he is not interested in perpetuating past power imbalances that leave the Huna Tlingit poor and indebted to those with power and resources. In the same sense, Bob is not interested in re-hashing the events of the past or dwelling in the past (although this is not at all to say he does not respect tradition). He is interested, however, in talking about the future, and cementing the progress they have made with the National Park Service, Forest Service and other agencies in co-management of their lands, even as he and other local leaders look toward retirement. Finally, in addition to Bob, I want to thank the entire community of Hoonah, including Bambi, Jolene, Jerry, Bill, Owen, Herb, Amelia, Zach, Ian, Don, Sherry, Sean, Gordon, Mary Beth, Dave, and a host of other people whom I didn’t officially meet, but who nonetheless warmly welcomed us and shared their personal stories with us. Gunalcheesh to all of you!

We are grateful to Former Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell, and Superintendent Philip Hooge for joining us, along with Mary Beth Moss (NPS cultural liaison), in a lengthy discussion at Xunaa Shuka Hit. Mary Beth, as a 20+ year employee of the NPS at Glacier Bay, and resident of Hoonah, is really the initiator and institutional memory for all of the events culminating in this summer’s healing pole ceremony. Philip has been an instrumental player and promoter of the most recent conciliatory events at Glacier Bay, and Sally in her time at Interior, was instrumental in promoting these kinds of conciliatory actions between the Federal Government and tribal governments across the country. Sally also holds a big picture view, from the past and into the future, along with knowledge of the inner workings of our political system, that helped us grasp the uniqueness and vulnerabilities of the arrangements of what we were witnessing between Glacier Bay National Park and the HIA. Sally joined us for several more discussions around the campfire, and nearly paddled away with us on the first day of our kayak trip!

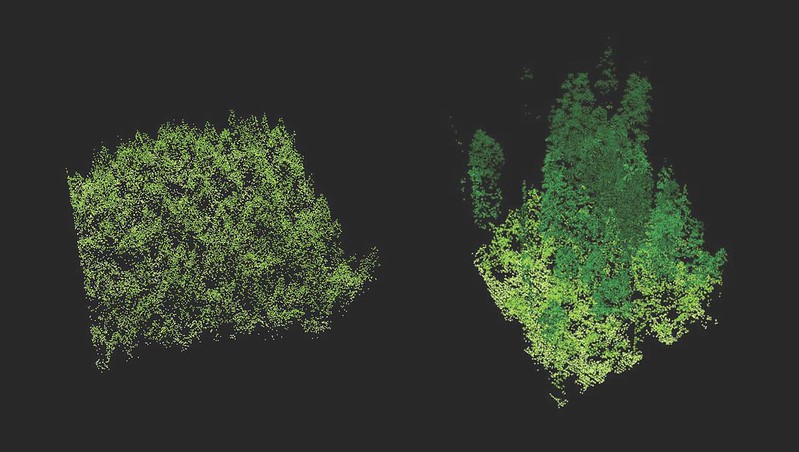

Just prior to our kayak trip, ranger Matthew Cahill joined us to update us on some of the science and natural history studies happening in Glacier Bay. On our kayak trip, we were thankful for the backcountry skill of Sean and Condor of Alaska Mountain Guides. On our return to Bartlett Cove, we were grateful to learn from ranger Cristina Martinez who sat down with us to discuss issues of diversity and access (from both a visitor and employee standpoint) in the national parks. Many of Cristina’s ideas are now weaving their way into student papers, and speak to broader issues in the Park Service.

In Gustavus we were graciously hosted by Kim and Melanie Heacox, both of whom, as I explain in the section “how the course came to be,” really set the ball rolling and made many introductions. They also hosted us for a final dinner and discussion at their beautiful house (future site of the John Muir Alaska Leadership School). Park Service bear biologist (and talented musician) Tania Lewis met with us to discuss the science behind cultural subsistence practices in the park. Lynn and George Jensen talked to us about “homesteading” in Alaska while we toured their cabin and property, and Zack Brown of the Inian Islands Institute provided a roof over our heads at his house for our final two rainy nights in Alaska. Last but not least, we are grateful to the fine folks at the Outpost, and the entire music community of Gustavus, for putting on a music night for us and welcoming us into their community.