Research by Jaffe Group postdoctoral scholars Dr. James Laing and Dr. Boggarapu Praphulla Chandra has resulted in two new peer-reviewed publications. Both papers examine methods used for measuring air pollutants from wildfires.

The first paper, “Comparison of filter-based absorption measurements of biomass burning aerosol and background aerosol at the Mt. Bachelor Observatory,” was recently published in Aerosol and Air Quality Research. The authors, Dr. James Laing, Dr. Daniel Jaffe, and Dr. Arthur Sedlacek, III, evaluated the upgraded aethalometer (AE33, Magee Scientific) and the new tricolor absorption photometer (TAP, Brechtel) to assess their effectiveness in measuring wildfire aerosol plumes. These instruments measure light-absorbing organic aerosols, which are emitted primarily in biomass burning. Both instruments were deployed at Mt. Bachelor Observatory (MBO) in central Oregon during the summer of 2016. Each instrument uses a similar methodology (“light extinction through an aerosol-laden filter”), but each has a unique set of corrections necessary to address filter-based bias and other issues. The coauthors found that when using the AE33 manufacturer’s recommended settings, correction factors that are larger than the manufacturer’s recommended factor are needed to calculate accurate absorption coefficients and equivalent black carbon.

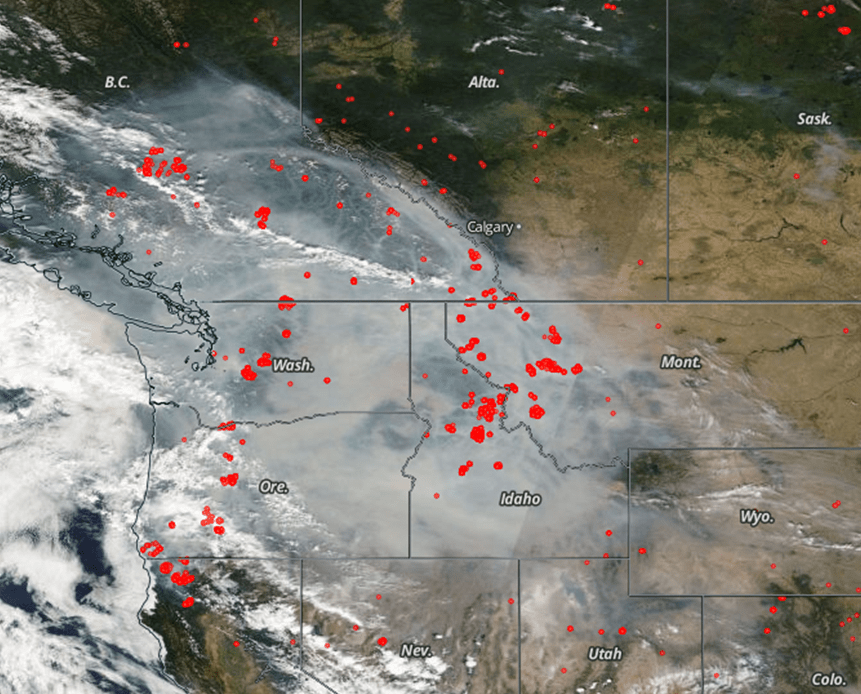

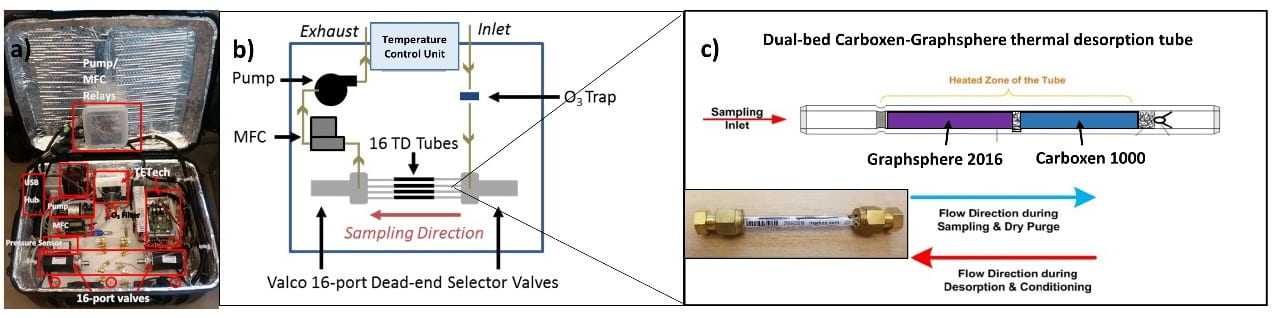

In the second paper, coauthors Dr. Boggarapu Praphulla Chandra, Dr. Crystal McClure, JoAnne Mulligan, and Dr. Daniel Jaffe evaluated the use of dual-bed thermal desorption (TD) tubes with an auto-sampler to sample volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Their paper, “Optimization of a method for the detection of biomass-burning relevant VOCs in urban areas using thermal desorption gas chromatography mass spectrometry,” appeared in the journal Atmosphere in March. For this study, the authors utilized a portable, custom-made “suitcase” sampler, which they deployed in Boise, ID, during the summer of 2019.

The sampler continuously collected samples of VOCs on the TD tubes for up to six days without the need for continuous on-site monitoring. The tubes were later transferred to the lab for analysis using thermal desorption gas chromatography mass spectrometry (TD-GC-MS) to detect VOCs.

They found that “reactive and short-lived VOCs such as acetonitrile (a specific chemical tracer for biomass burning), acetone, n-pentane, isopentane, benzene, toluene, furan, acrolein, 2-butanone, 2,3-butanedione, methacrolein, 2,5- dimethylfuran, and furfural . . . can be quantified reproducibly with a total uncertainty of ≤30% between the collection and analysis, and with storage times of up to 15 days.”

Their research demonstrates the applicability of this flexible method for ambient VOC speciation and determining the influence of forest fire smoke. This sampling method offers a practical alternative for urban air quality monitoring sites because its portability does not require the installation of a complex and expensive instrument and its auto-sampling technique does not require continuous on-site monitoring.