Main Takeaways:

- Late-onset Alzheimer’s Disease (LOAD) is influenced by many genetic and environmental risk factors. There is no gene that guarantees onset or immunity from (LOAD).

- At-home genetic testing companies that offer an “Alzheimer’s test” are only testing one variant from one gene (APOE). The presence or absence of this APOEε4 variant is not a diagnosis.

- Thus far, over two dozen risk loci for LOAD have been discovered, yet a genetic test is not sufficient to detect one’s true risk of developing disease.

When I was seven years old, my parents took me back to their hometown of Shanghai to visit my grandparents. It was a long trip we had taken before, and while the 18-hour journey was tiring, I was looking forward to seeing family, eating street food, and finding cats in the park. This trip was different, however. My mom explained to me that my grandpa may not remember us. He has Alzheimer’s, she said. Although I didn’t know what that meant, it made sense to me that my grandpa may not remember me. After all, I had changed a lot between three and seven. When we finally arrived at my grandparents’ home, I realized that it wasn’t that my grandpa was forgetful; there was a blankness. He couldn’t leave his bed.

My grandpa was suffering from a neurodegenerative disease – meaning it affects the brain and becomes worse over time. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, affecting an estimated 5.8 million people in the United States and 1 out of every 10 people over age 65 [1]. The disease is devastating for those affected, their caregivers, and their loved ones. When 23andMe and other at-home (direct-to-consumer) genetic testing companies began testing for Alzheimer’s disease risk, I understood the impulse to spit in a tube and find out one’s genetic risk for the disease [2]. That impulse is driven by the feeling of fear that immediately follows annoyance when my mom turns the car back around two minutes after leaving the house because she can’t remember if she left the stove on. Of course, I want to know my risk for disease and everything I can do to prevent it. The fact is, that’s just not possible yet.

That impulse to order the genetic test is also based on the misconception that all of the genetic causes of Alzheimer’s disease are known. Last year Cosmopolitan published an op-ed titled “I tested positive for the Alzheimer’s Gene at 26 years old,” where the author shared her emotional experiences after receiving her genetic testing results and the lifestyle changes she made to help prevent the disease [3]. While I don’t believe genetic testing companies are trying to be scientifically deceiving, the op-ed highlights the consequences and unwarranted anxiety that can occur when the science and genetics of Alzheimer’s disease are not clearly presented. In this post, I will share the facts about Alzheimer’s Disease genetics. (For the rest of this post, Alzheimer’s Disease will be referred to as AD).

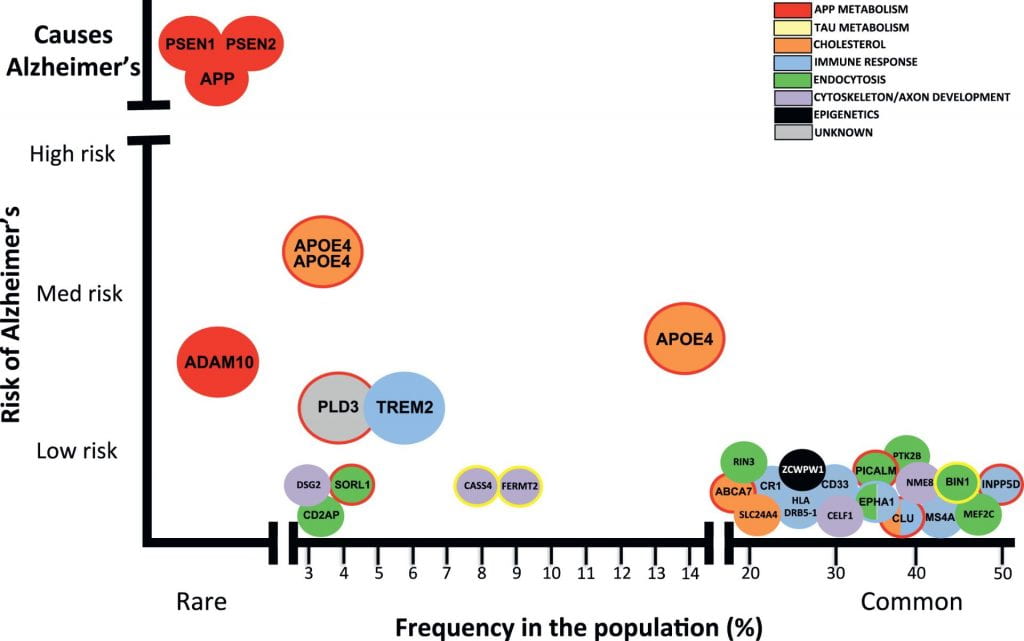

There are two classifications of AD: early-onset AD and late-onset AD. Early-onset AD is rare. It accounts for about 1% of all AD cases [4]. Unlike most AD cases, the genetic causes of early-onset AD are known; it is caused by mutations in the genes APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2. Early-onset AD is transmitted in a dominant Mendelian pattern. For every gene, you receive one copy (allele) from your father and one from your mother. A dominant Mendelian pattern means that if you receive just one copy with a mutation, you will develop the disease. Once again, I want to reiterate that this type of AD is very rare. If you have a family history of early-onset AD and are not in contact with a medical provider or research group, you can find more information and resources here [5].

The more common version of AD, the type that my grandpa had and the version most direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies offer a test for, is late-onset AD. Unlike the early-onset version, late-onset AD is a complex, genetically heterogeneous trait, meaning it is influenced by both environmental and genetic factors. Furthermore, different genetic variants cause the disease in different people. In other words, there is no “Alzheimer’s gene.” There are many variants in many genes that add to one’s genetic risk, and many risk variants have not been discovered yet.

So why the hype? What is the scientific basis for the direct-to-consumer late-onset AD tests that have resulted in online forums, Facebook support groups, and op-eds in popular magazines?

The direct-to-consumer tests calculate genetic risk based on the variation in a single gene: APOE. Everyone has the APOE gene on chromosome 19; what matters for AD risk is which variants of the gene you have [6]. There are three variants (six possible combinations): ε2, ε3, and ε4. APOE ε2 has been found to have protective effects, while APOE ε4 is the variant associated with an increased risk of late-onset AD. Studies have found that on average, having one copy of ε4 increases the risk for late-onset AD by 3-fold, and having two APOE ε4 alleles increases risk by 12-fold [4].

I am not trying to dismiss concerns over this increased risk; three times higher and twelve times higher risk are significant. APOE ε4 is the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset AD that we know of. However, it is important to keep the following in mind:

(1) Inheriting two copies of APOE ε4 is rare, affecting only 2-3% of the population (see image below) [4].

(2) Late-onset AD is influenced by genetic risk factors AND environmental factors, with one study showing that 47% of the variance of AD is due to non-genetic factors [7].

(3) Having two copies of APOE ε4 is not an Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis, nor is the absence of APOE ε4 a guarantee that you will not get AD. Environmental factors aside, there are many other genetic variants that confer risk for late-onset AD (see image below).

(4) Finally, the overwhelming majority (over 90%) of research on the genetic risks of Alzheimer’s have been conducted in samples of people of non-Hispanic European descent [8]. The few studies of APOE risk on AD in diverse populations have shown that the risk of AD caused by the APOE ε4 allele varies depending on ancestry. In 2019, a study of late-onset AD in Caribbean Hispanics found that individuals with African-derived ε4 allele at the APOE gene had 39% lower odds of having AD than those with a European-ancestry-derived copy of ε4 [9].

Image from Celeste M. Karch, and Alison M. Goate, “Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Genes and Mechanisms of Disease Pathogenesis.” Alzheimer’s risk-variants are plotted with frequency in the population on the X-axis and the risk conferred by each variant on the Y-axis. Mutations in PSEN1, PSEN2, and APP cause early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Dozens of genetic mutations have been confirmed to increase risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, with APOE ε4 being the strongest known disease-variant.

The bottom line is that these direct-to-consumer genetic tests of late-onset AD can tell you one piece about your risk for disease, but it can’t factor in how APOE interacts with other genes or with your environment; the test is based primarily on research of those with European ancestry; and it cannot tell you whether or not you will have Alzheimer’s disease. I look forward to the day when I can edit this post to say that an accurate assessment for late-onset AD genetic risk exists, but we’re not quite there yet. (note: if you are thinking about ordering an direct-to-consumer genetic test for AD, the Alzheimer’s Association strongly recommends you consult with a genetic counselor before the test and after receiving your results).

That trip in 2004 was the last time I saw my grandpa. At the time, I didn’t know what was happening, but I could feel the hopelessness in the air. It hits kids hard when the adults in the room are saying they don’t know anything more, that nothing can be done. I understand that it can seem discouraging that there is so much we still don’t know, that there is still no cure. But I am not hopeless anymore. In 2004, studies of the human genome were in its infancy, with The Human Genome Project having been completed only months before. At the time, there had been no genome-wide studies of Alzheimer’s disease. In the past 15 years alone, 40 genomic regions that are associated with late-onset AD have been found [10]. Every year, we learn more about new risk variants and biological pathways that can be targeted for pharmaceutical therapies. Significant efforts are being put toward researching the genetics of Alzheimer’s, worldwide, with the hope that one day we will understand the entire genetic architecture of the disease. I am optimistic for what the next 15 years will bring.

References:

[1] 2020 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Association. Retrieved from https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf

[2] Late-onset Alzheimer’s Disease. 23andMe. Retrieved from https://www.23andme.com/topics/health-predispositions/late-onset-alzheimers/

[3] Brown, S. “I Tested Positive for the Alzheimer’s Gene at 26 years old.” Cosmopolitan Sep. 19, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.cosmopolitan.com/health-fitness/a29107622/alzheimers-gene/

[4] Karch, Celeste M. and Alison M. Goate. 2015. Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Genes and Mechanisms of Disease Pathogenesis. Vol. 77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.05.006. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006322314003394.

[5] Younger/Early-Onset Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Association. Retrieved from https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/younger-early-onset

[6] Roses, Allen D. and Ann M. Saunders. 1994. APOE is a Major Susceptibility Gene for Alzheimer’s Disease. Vol. 5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0958-1669(94)90091-4. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0958166994900914.

[7] Ridge, PG, Hoyt, KB, Boehme, K et al. 2016. Assessment of the genetic variance of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. Vol. 41 doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.02.024.

[8] Popejoy, AB, and Fullerton, SM. 2016. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature, 538(7624), 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1038/538161a

[9] Blue EE, Horimoto ARVR, Mukherjee S, Wijsman EM, Thornton TA. 2019. Local ancestry at APOE modifies Alzheimer’s disease risk in Caribbean Hispanics. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: the Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. Vol. 12. doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.07.016

[10] Andrews, Shea J., Brian Fulton-Howard, and Alison Goate. 2020. Interpretation of Risk Loci from Genome-Wide Association Studies of Alzheimer’s Disease. Vol. 19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30435-1. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1474442219304351.

Recent Comments