In a course about the food system, it makes sense that we have time dedicated to digestion, to contemplation. To the breaking down and consideration of our place within the complex global food system.

But truth be told, my experience with these contemplative practices have been mixed. They have provided me with a chance to dive into my own experiences relating to food and to the world beyond my immediate reach. But there have been times when I simply could not comfortably sit through a full practice. I had to ask myself why did I have this sense of restlessness? I found that my response to the practice is dependent on two things: content and headspace.

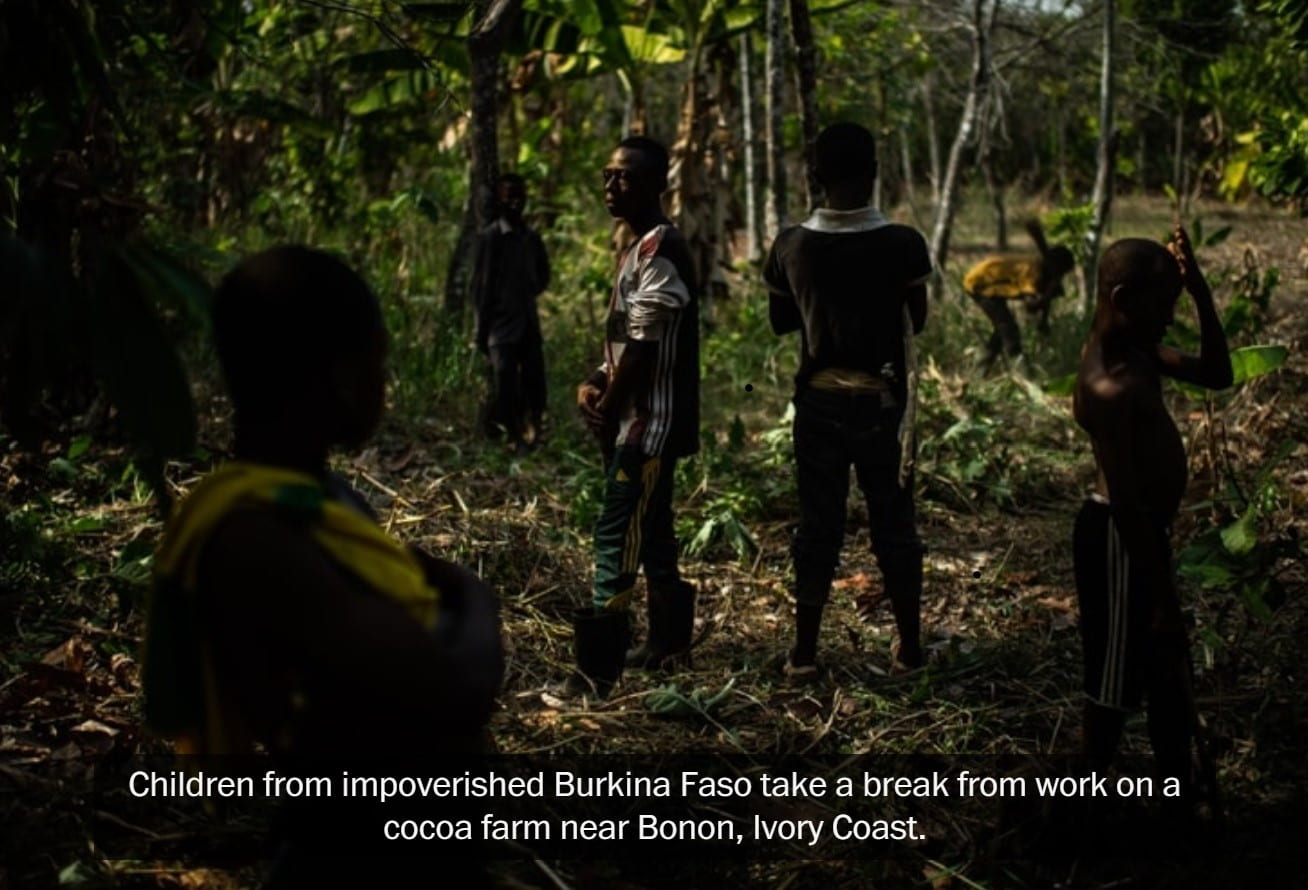

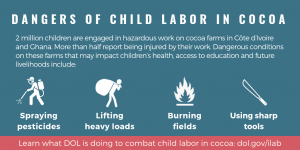

Contemplative practices will often require that I reflect on my own privilege within the food system. I recall sitting through a practice reflecting on the production of chocolate, and throughout this practice I alternated between feeling restless and driven as I began to try to figure out ways that I, as both a consumer who benefits from the current production methods and as a citizen who finds the use of unpaid labor appalling, could make a difference that actually matters.

I had entered this practice with a relaxed and clear mind, unlike days where I had entered a practice feeling mentally exhausted. Having a clear headspace allowed me to delve into the mixed feelings and thoughts I had in a constructive manner. On days where I enter feeling strained, I struggle to escape my anxieties and to focus my mind on the material.

Image is my own and may not be used without my permission; illustration of introspection within a particular headspace

These practices have ultimately led me to the following conclusion about how we approach systems: finding solutions to a complex problem first requires an analysis of one’s relationship to it, yet such analysis cannot be effectively done by an exhausted mind.