Political Ecology of Death in the Anthropocene views the world with “Systems Theory.” To me, this means understanding that everything is part of something more than itself.

In “Terror Management Theory”, psychologist Sheldon Solomon argues that our fear of death leads us to strive to “become part of something less mortal…[to be] a person of value in a world of meaning” (Vedantam 2019). However, even if we do not actively pursue it, we are already part of something bigger than ourselves, something immortal. Even when we are alone on a desert island we are not alone. The fish provide minerals for us to function. Our waste provides nutrients to the worms. There is no “self.” We are already part of something valuable and meaningful.

Source: Summer Grassland by Kathryn Foster

I feel a sense of peace when I think of myself from this perspective. I imagine myself as a blade of grass in a painting. I sway with the wind alongside other blades of grass as the sun provides us energy and the air provide us food. However, one can look at this blade of grass from another perspective. It must compete for resources and lives in fear of being eaten by herbivores. Thus, it grows the deepest roots to uptake the most water and releases chemicals to defend itself.

I think it is the latter perspective that dominates our society. Solomon argues that the fear of death also leads to “self-esteem striving,” where individuals work to be “better, smarter, richer” to further make meaning of our lives (Vedantam 2019). When we do not think of ourselves are part of a greater system, we must expand ourselves to not be overtaken by others. The only value we have is our own value, and the only life we further is our own.

But even when that blade of grass is overtaken by other blades of grass or eaten by herbivores it lives on within others. We always live on.

As Professor Karen mentioned, I also think this world is amid a “transition” from a perspective of self to a perspective of the whole. In the Anthropocene where humans touch every part of the world, we have no choice but to recognize the world as connected. Perhaps as we grow more aware of this wholeness, we can create new systems of functioning to account for the impact our choices have on the world.

Work Cited:

Foster, Kathryn. Summer Grasslands. 2009, Fine Art America, https://fineartamerica.com/featured/summer-grasslands-kathryn-foster.html.

Vedantam, Shankar, host. “We’re All Gonna Die! How Fear of Death Drives Our Behavior.” Hidden Brain from NPR, 16 September 2019, https://www.npr.org/transcripts/760599683.

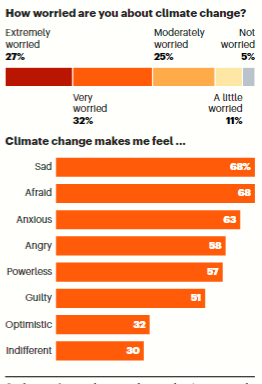

![[Image description of second image]: An image taken from Nature’s landmark survey of climate anxiety. At the top is a sliding bar measuring respondent’s climate anxiety from “extremely worried to not worried”. The statistics read, “extremely worried: 27%, very worried: 32%, moderately worried: 25%, a little worried: 11%, not worried: 5%”. Below the bar, is a phrase that reads “climate change makes me feel…” with a series of different emotions and represented percentage in bars. The varying emotions and related percentages read, “sad: 68%, afraid: 68%, anxious: 63%, angry: 58%, powerless: 57%, guilty: 51%, optimistic: 32%, indifferent: 30%”](https://sites.uw.edu/pols486autumn2022/files/2022/10/Screen-Shot-2022-10-10-at-5.02.05-PM-300x259.png)