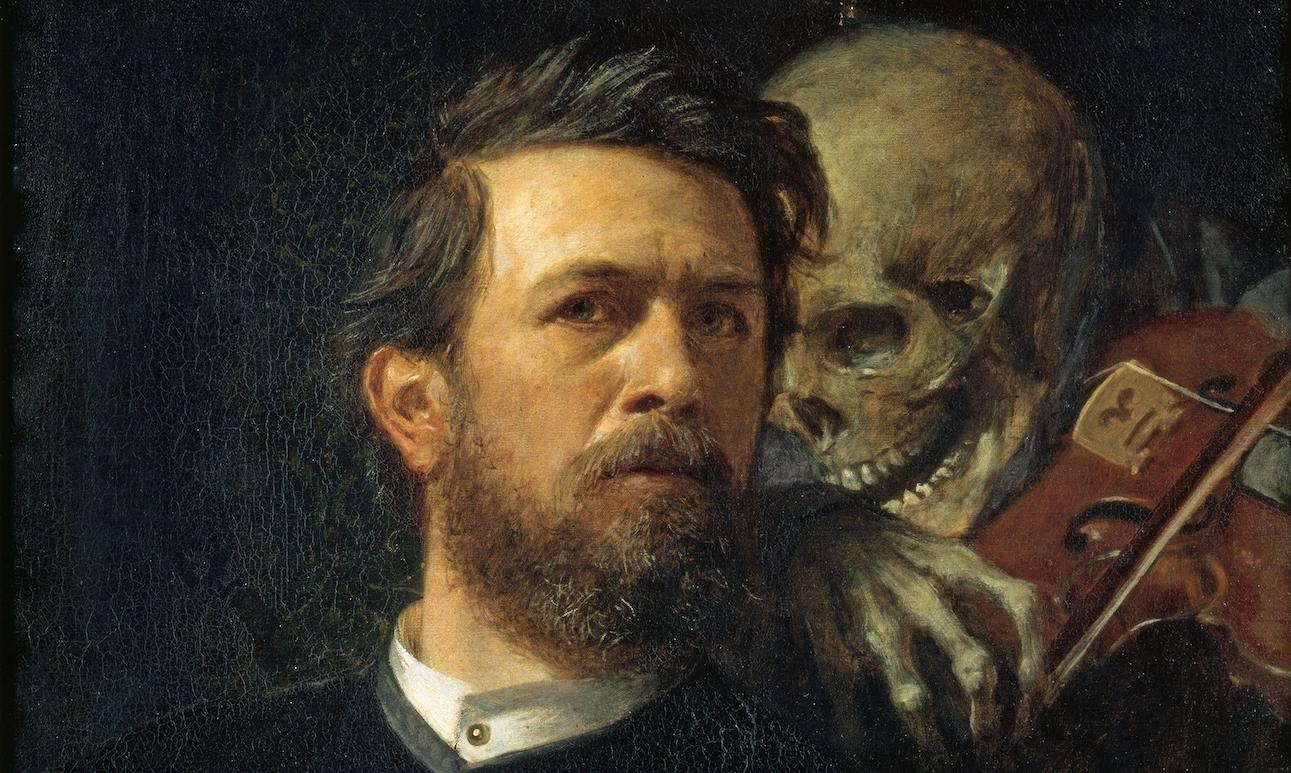

Throughout this class, I think I’ve realized one thing. Nothing is set; reality is perception. Facts are relative, and the truth is relative. The only real thing we have is the inevitability of death. In Baldwin and Buddhism: Death Denial, White Supremacy, and the Promise of Racial Justice James K. Rowe quotes James Baldwin.

“Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have.”

In short, death is the one thing we can rely on. We focus a lot on the present during these past few cognitive practices. I’ve noticed that these reflections are centered around processing the current moment.

This might not be directly related to the course, but I think these contemplative practices have made me realize that to acknowledge death is to appreciate life.

In class, we talk alot about terror management because of its centrality to the course, but we never ask the question that I think is critical to understanding human behavior, “Is terror management essential to living a fulfilling life? If we didn’t have lows, we wouldn’t appreciate highs. Terror management is ingrained in our human psyche; if we are products of evolution, terror management must be an important part of human survival. Why do we deny something we cannot control? And what is the evolutionary benefit of existential self-consciousness? If death is inevitable, why are we made to fear it?