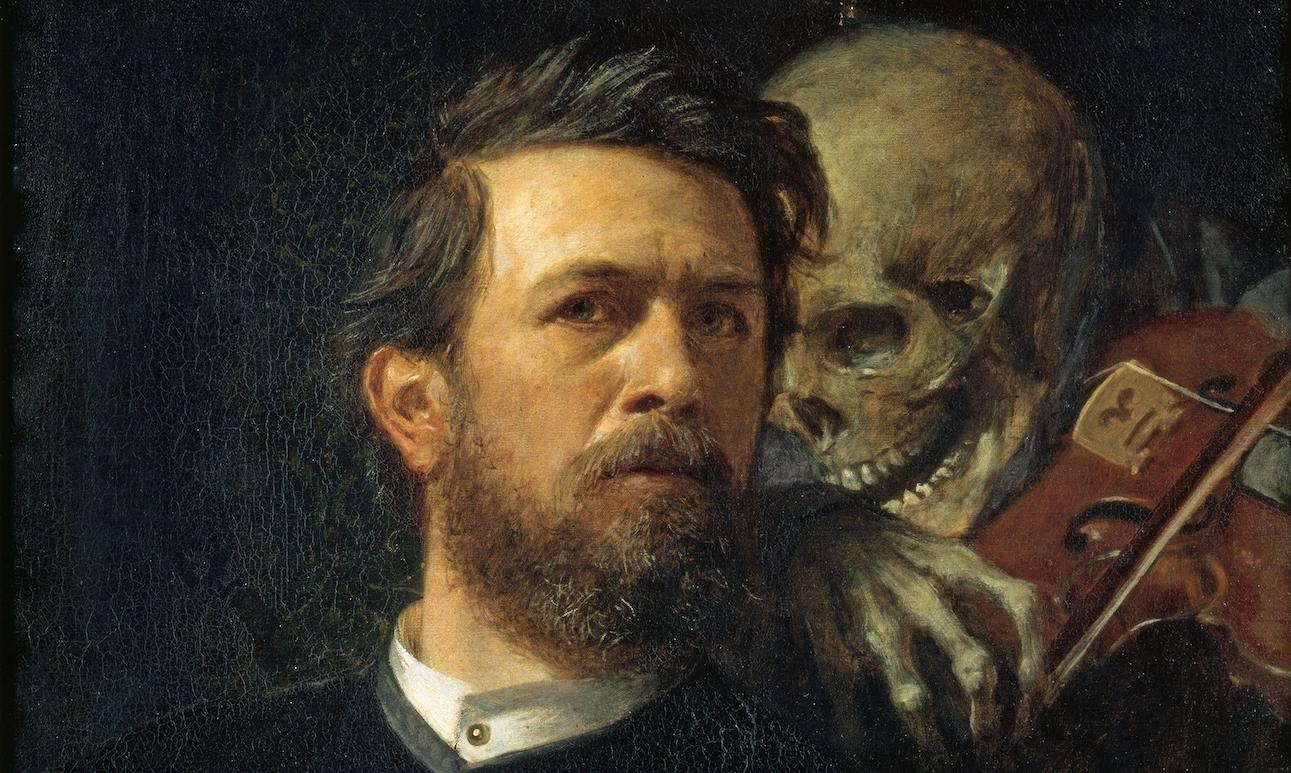

“Depression” by Disability Arts Online

On October 13th, Professor Litfin prompted us to “scan” our bodies during a contemplative practice. When I got to my chest, I felt a vast heaviness, taking the form of a dark hole near my heart. With each beat, I visualized the darkness “leaking out” into my veins, seeping throughout my body, carrying waves of what felt like grief and guilt. The more focused I became on the darkness, the more class images flashed through my mind – specifically, bits and pieces of the movie we had watched the Tuesday before (The Anthropocene). Abruptly, I realized I had internalized course materials, such as the feelings of climate guilt, without even realizing how much they were affecting my physical or mental state.

One of my favorite books, “Untethered Soul”, stresses the importance of “untethering” yourself from negative emotions/experiences so that your body does not harbor (and build) upon them. While I felt I had mastered this practice, I was violently surprised to learn that I was internalizing feelings directly related to what I was learning in my classes. In my conceptualization of mindfulness and wellbeing, I had divorced education from my personal well-being, despite the fact that everyday I was learning about environmental degradation, crimes against humanity, war atrocities, and the psychological consequences of the death-penalty.

“Untethered Soul” by Michael Singer

Since this realization, my notes post-contemplative practice have continued to illuminate the intersections between course materials and personal quandaries, which have allowed me to more deeply engage in both. While October 13th brought me insight to guilt and grief related to living in a capitalist society and trying to preserve the environment, contemplative practices on October 18th and 25th indicated that I was really struggling with the idea of death anxiety and was more aligned with the idea of death apathy. This facilitated my interest in nihilistic-like attitudes (especially for younger generations), which is an idea that has made an entrance into each one of my blog posts and usually at least one comment in each class.

As I reflect on the use of contemplative practices in the classroom, I am astounded at the insight they have brought me. It seems so obvious that students internalize the psychologically “weighty” lessons they learn in class, but for the past three years, I’ve been oblivious. It prompts me to wonder what my education (and personal self-awareness) would have looked like if I had been practicing in classrooms before this quarter.