December 12, 2020

Mapping Maps: Cataloging UW’s Gaihōzu Collection

Ross Henderson

This summer, I had the pleasure of working as a Student Specialist at the Tateuchi East Asia Library, assisting Japanese subject librarian Azusa Tanaka and cataloger Keiko Hill with various projects. The libraries, like most parts of the University, were closed because of COVID. Unfortunately this meant that I worked remotely for the entire summer. As much as I enjoy the commute between my bed and my desk, the East Asia Library would have been a beautiful space in which to work.

I helped to find bibliographic records for backlogs using a union catalog called OCLC Connexion, and wrote weekly posts for the library’s Facebook page. Most of my time, however, was spent with one particular project (also the subject of one of those Facebook posts): Gaihōzu.

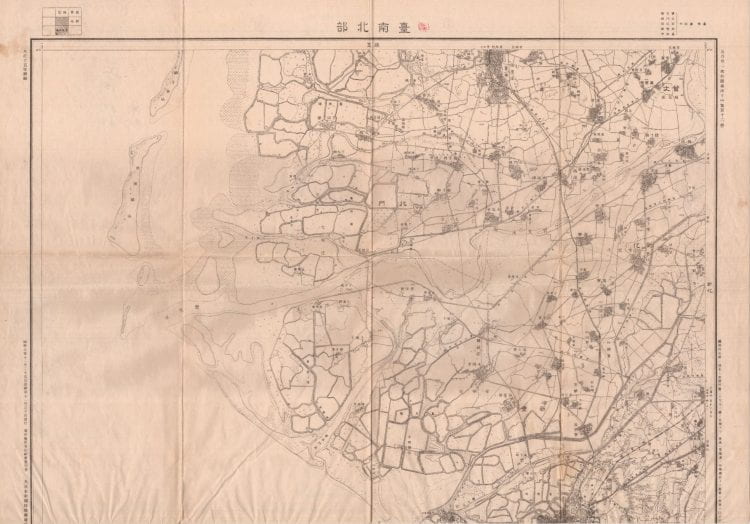

Quoting my earlier Facebook post, Gaihōzu are “topographic survey maps of colonially occupied territory created by the Imperial Army General Staff Headquarters, beginning in the 1880s and ending in 1945. Because of their military-strategic nature many were destroyed at the end of the Second World War, making large collections like UW’s very rare.”

My first task with Gaihōzu, as with cataloging Japanese monographs, was to find bibliographic records created by other institutions. Major holdings can be found at the Library of Congress and a handful of academic libraries, particularly Stanford University. Finding existing records for our uncataloged maps is important both to make sure that the UW collection is cataloged correctly and, critically, so that UW’s items can be searchable in the international union catalog WorldCat. I’m a graduate student, so in a sense searching for things in library catalogs is my job. I thought that it would be easy. It was not.

Note the length of time during which Gaihōzu were produced: more than sixty years, the entire stretch of the Japanese state’s colonial campaigning. As conditions and strategic interests changed, many areas were surveyed repeatedly. Sometimes a different name would be applied to the same area and, more frustratingly, the numbering system used by the surveyors themselves to designate maps went through a number of iterations, making it difficult to understand how individual map areas relate to each other in space. What’s more, no two libraries catalog their Gaihōzu in exactly the same way. This isn’t sloppiness on the part of catalogers. All standard cataloging procedures are followed, but libraries are still in the process of working together to determine how best to make Gaihōzu accessible while still keeping track of the large amount of information on each individual map. This is further complicated by the fact that Gaihōzu were meant to be used, and many of the printed maps have strategically sensitive information written in later by hand, adding another layer of complication to the cataloging process.

Within the Gaihōzu cataloging project, I dug most deeply into maps of Manchuria, particularly a certain series at 1:100,000 scale. Stanford also has a sizable number of this series in their collection, and make them conveniently browsable on an interactive map through their library’s website. I was asked to compare our holdings with Stanford’s to see how they complement each other, but immediately encountered all the problems discussed above. I could see the Stanford maps, but had to rely on data in a spreadsheet for the UW collection as I had no access to the actual maps while the libraries were closed due to the pandemic. Though much of the information matched neatly, I began to notice that seemingly identical maps—with matching place names and geographic coordinates—used different numbering systems. It was apparent that these systems were, well, systematic, but not at all clear how they related to one another. There must be a code, I thought, and cracking it became a fixation.

Examining Stanford’s digital index, I saw that the maps were grouped individually and numbered into squares of twenty-five (5×5). Stanford laid out these maps in a simple grid, letters on one axis and numbers on the other, giving maps designations like D-3-12. The Japanese Imperial Army, however, used three different schemas. Briefly: 1) A larger area was named, and each map was numbered: Harbin 15 (哈爾濱十五號). 2) To that could be added coordinates that seem clear enough, but weren’t indexed to latitude and longitude: W4N10 (西四行北十段). It seemed that one area designation corresponded to one set of coordinates, but it wasn’t clear how big that area was. 3) The last system was the most mysterious. Two numbers were given in “daiji” 大字 alternative-form kanji numerals, followed by a katakana character, and then three conventional kanji numbers: 壹壹タ一〇七.

Remembering how I used to use graph paper to keep track of videogame maps when I was young, I decided to do the same thing, using Stanford’s grid as a base and noting down the number of each map in whatever system it used once I had pinpointed its location. Slowly but surely—but slowly—the pattern revealed itself. Whether or not named areas had W#N# coordinates didn’t matter. They were part of the same system. These coordinates also mapped neatly onto Stanford’s system. A-1 was W1N12, B-2 was W2N11, and so on. West and East were measured from the 135th meridian east, the line from which Japanese standard time is measured. Each of these larger squares corresponded to a named and numbered group of twenty-five maps.

The last system, which used kanji numbers in two different formats, also fit onto the same grid. The daiji numbers and katakana characters designated 10×10 groups of 100 maps, corresponding to four of the smaller 5×5 areas mapped by Stanford’s and the W#N# system. Most interestingly, the katakana that had seemed random in fact proceeded from south to north in i-ro-ha order. I was even able to figure out how these different systems related to latitude and longitude, an added bonus. (It appears that the i-ro-ha start at 3°20′ North, rather than the equator, but this is far outside the range of the maps I was working from and I may have miscalculated.)

Of course, I hope that making these correspondences clear will help researchers and catalogers in the future, but more than anything this was an exceedingly satisfying puzzle to solve.