Basic Information

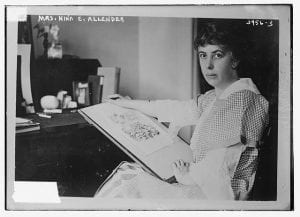

Nina Allender was a woman inspired by her mother to become active during the first wave of feminism. Her greatest contribution was being a cartoonist and reforming how women were being viewed by the public.

Background Information

Nina Evans Allender was a woman that was a driving force in re-defining how women activists were being portrayed. However, before getting into her contributions in the first wave of feminism, it is best to lay out her background information, in order to see what drove and inspired her. Starting at the very beginning, Allender was born around 1872 near Topeka, Kansas and was raised primarily in a single-parent household. As her father was not a part of her life, there was not a name that could be found for him. Her mother on the other hand was Eva Evans, she is an important person to be highlighted in her daughter’s life because she is one of the reasons Allender became a part of the first wave. (Sheppard, 1985, pp 45)

Eva Evans was an independent woman that began working at the very young age of 16. She was a school teacher on the Kansas prairies and within the following year, she was married to Nina Allender’s father. She was also a woman that held strong beliefs, in fact since she did not find the marriage satisfactory she ended up leaving her husband, a step that was viewed as unusual for that day and age. Afterwards she took her two young daughters and began a new life in Washington D.C. (Sheppard, 1985, p. 45), allowing her daughters, especially Allender, to develop who she was and do what she loved. From a very young age, there were signs of talent for drawing and Allender studied locally at Corcoran School of Art and even abroad (Propogandist). As Allender was pursuing her dream to become an art teacher, she met an Englishman by the name of Charlie Allender.

Charlie Allender is mentioned to be another reason as to why she became interested in women’s suffrage. The two of them were not married very long, in fact he did not even divorce her formally. It was just another normal day in Allender’s life when Charlie vanished from the bank where he was working at, along with a certain amount of money and an unnamed female coworker. There is no certainty in knowing if that was another event that was significant in her becoming active in the movement. Though according to her relatives Allender was unhappy and a depressed woman afterwards. After some time, she took comfort and followed her mother’s example of being independent and strong-willed. Taking control of the life she had and getting a government job for the Treasury Department while also being active in the Arts Club of Washington. (Sheppard, 1985, pp 45)

Contribution to the First Wave

As Allender began to take control of her life, she did not immediately begin her work as a cartoonist. Instead, she held office in many suffrage organizations in Washington and became a leading activist in the movement. Even though she was working full time, Allender was able to go canvasing door-to-door. For the 1912 referendum she joined the NAWSA workers and it would not be for another two years, 1914, that Alice Paul would visit Washington and be the one to nudge Allender in doing cartoons. (Sheppard, 1985, p. 46) She would become the suffrage movements cartoonist officially, even though her training was more for the traditional kind of art. (Walton, 2015, pp 61)

Nina Allender viewed herself as more of a painter, there was hesitation towards the beginning of her endeavors of being a cartoonist. Though that uncertainty became quickly forgotten as her cartoons were showcased weekly on the cover of the Suffragist newspaper. Her cartoons became a trademark and “Allender’s initial suffrage art consisted of realistic illustrations, which gradually became more symbolic and political.” (Sheppard, 1985, p. 46) The symbolism that was used within her cartoon relied on the president, congress, and suffragists. (Sheppard, 1985, pp 48) Her earlier works played off traditional gender roles and she soon began to create works that featured that were then labeled as the “Allender girl.” (Propogandist)

The “Allender girl” became an important symbol because of the pieces of work male cartoonists were presenting to the public. “Male cartoonists often drew suffragists as unattractive old maids with thick spectacles and wielding battle axes, or portrayed them as too hysterical to vote.” (Myers, 1995, pp 32) Allender used her talent and created cartoons that counteracted the negative. Cartoons that were created allowed the Women’s party to define who they were, rather than to allow the stereotypes to take control. (Endres & Lueck, 1996, pp 369) Though she was not alone in fighting against the unjust way of how they were being portrayed, since Annie Lucasta “Lou” Rogers and Blanche Ames drew cartoons as well. The three of them began to turn things around with their political cartoons that were witty, sharp, and attacking the power that was trying to silence them. (Bass, 1995) This new and modern-day women that was being depicted as the “Allender girl,” showed a spirit of daring and pride as well as possessing youth. (Sheppard, 1985, p. 46) Though it should be stated they were not the only ones doing so, but they were seen as the ones leading the cause.

As the movement began to progress, Allender became more critical and confrontational as arrests for suffrage picketers multiplied. There was one cartoon, “Celebrating Independence Day in the National Capital,” that radiates the struggle suffragists were facing. In this cartoon it depicts one woman that is holding a banner and is being threatened by a mob of citizens and police officers. Though it was once said that her work was not characterized as hostile, but more of bewilderment. (Endres & Lueck, 1996, pp 396) Her cartoons were one of the most major contributions Allender gave to the first wave because of the impact it had on people.

“A cartoonist and artist who campaigned vigorously . . . for women’s suffrage.”

~ New York Times (Sheppard, 1985, p. 48)

Analysis and Conclusion

Nina Allender was able to recreate how others were trying to portray suffragists and even give a form of hope. Hope that the movement was striving for equality and for a better tomorrow. Even though the male cartoonists kept releasing pieces of work that tried to undermine and discredit these women, creating barriers and stereotypes that would paint them in a horrible way. Allender, Ames, and Rogers led a movement that contained a few dozen female cartoonists, (Myers, 1995, p. 32), each trying to work against the counter movement that was being presented to them. They changed the public view of women into a more positive depiction,that is why there was such an importance for the “Allender girl.” This piece of symbolism had a similar description of what it meant for the women back during the first wave. A symbol that had represented strength, pride, feminine, and youth. A modern woman that they were trying to strive for and become, it was a form of empowerment for them.

Allender was a remarkable woman and yet not much can be found about who she was as a person. It can be assumed that she was in the middle class because of a newspaper section from The Daily Gazette, which mentioned that she was living a privileged sort of life. (Myers, 1995, p. 32) Why this is being highlighted is because what can be found of Nina Allender were contributions and cartoons. Meaning that she as a person is being lost in history as there weren’t any passages that could be found of her making statements. The only pieces that could be used in representing who Allender was were the captions used for her pieces of work.

References

Allender, N. E. (n.d.). Victory [Cartoon]. Retrieved May 22, 2019, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nina_E._Allender,_Victory,_September_1920,_The_Suffragist.jpg

Bass, H. (1995, September 1). Artful advocacy: Cartoons from the Woman Suffrage Movement. Washington City Paper.Retrieved from https://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/arts/article/13006751/artful-advocacy-cartoons-from-the-woman-suffrage-movement

Endres, K. L., & Lueck, T. L. (1996). Womens periodicals in the United States: Social and Political Issues. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Mrs. Nina E. Allender [Photograph found in Bain News Service, Library of Congress]. (n.d.). Retrieved May, 2019, from http://loc.gov.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/pictures/resource/ggbain.22583/ (Originally photographed 1915)

Myers, L. (1995, August 20). Cartoonists’ Role in Suffrage Debate Focus of Exhibit. The Daily Gazette, pp. 32-57. Retrieved April, 2019, from https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=tDpHAAAAIBAJ&sjid=bekMAAAAIBAJ&pg =5435,4338815

Propagandist. (n.d.). Retrieved May, 2019, from https://www.loc.gov/collections/women-of- protest/articles-and-essays/selected-leaders-of-the-national-womansparty/propagandist/

Sheppard, A. (1985). Political and Social Consciousness in the Woman Suffrage Cartoons of Lou Rogers and Nina Allender. Studies in American Humor, 4(1/2), new series 2, 39-50. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/stable/42573210

Walton, M. (2015). A Womans Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.