August 6, 2020

A Tale of TikTok and Tariffs – US Technology Policy towards China – By Victor Menaldo and Nicolas Wittstock

As China has become a more assertive international actor, US calls for active industrial policy to counter growing Chinese technological capabilities have grown. Allegedly, China’s technology companies are undermining US companies and hurt the US economy. Often “forced technology transfer” is invoked to justify the recent escalation in anti-Chinese technology policy. Yet, we argue that current Chinese processes are neither novel nor particularly alarming from the standpoint of economic efficiency; nor distribution, in fact: US firms doing business with China are collecting record royalty payments for their IP and generating gangbuster profits due to their access to Chinese labor, suppliers, and the country’s growing consumer market.

Sailing on the tailwind of strong, decades-long economic growth, China is flexing its political, diplomatic, and military power internationally. Exhibit A is the construction of artificial islands in the South China Sea and escalating belligerence towards its neighbors, especially the Philippines, Vietnam, and India (Kim 2015). Exhibit B is the draconian national security law it imposed on Hong Kong in July of 2020, thereby violating its 1997 promise not to infringe on the territory’s sovereignty and threaten its liberal political and legal system. Exhibit C is the debt trap diplomacy that has accompanied its so-called Belt and Road initiative, Xi Jinping’s attempt to recreate the trading networks that spanned Eurasia during the Tang’s Dynasty hegemonic silk road era. Exhibit D is China’s rapid military buildup in East Asia and beyond—and the fact that US superiority in the West Pacific is no longer guaranteed (Lague and Lim 2019).

China’s tremendous economic development since the late 1970s has catalyzed its political and military rise. Breakneck growth rates have sometimes approached 10 percent per year and, as the figure below shows, Chinese real living standards doubled twice between 1979 and 2006. While economic growth has slowed down since 2014 and China’s economy was initially hit hard by Covid-19, decelerating below 3% annualized growth, it has since recovered. Plus, China’s share of global GDP has grown steadily, irrespective of any change in living standards.

Given the fact that the United States was much wealthier than China going into this period, its Per Capita Income experienced a more muted rise: at most, it grew 3% per year; and, after the 2008 Financial Crisis, America’s average rate of Per Capita Income growth has been closer to 2%. The jury is still out on how strongly the pandemic will hurt its economy, but America’s share of world GDP is projected by most forecasters to continue a steady decline.

Parallel to China’s rise, under President Xi Jinping the Chinese state has become even more powerful. The Communist Party’s removal of term limits on the executive branch from the constitution in 2018 effectively allows Jinping to remain in power indefinitely; this followed his purging of key members of the Politburo’s Standing Committee. Beijing has introduced a nationwide “social credit system” that monitors and seeks to control its citizens’ behavior while rolling back civil liberties in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. It has also tightened restrictions on the press and citizens’ speech, especially social media (Qiang 2019).

Economic dirigisme has increased too. Large state enterprises have been “strategically” merged by Beijing to reach greater scale; Jinping has personally reversed privatizations of large portions of the Chinese economy. The Chinese state has bought shares in successful private firms, manipulated asset prices—through its intervention in stock markets, for example—revved up its subsidies to national champions, and promoted aggressive industrial policy in general. This follows decades of subsidies to exporters that have, at different points in time, included tax breaks, tariffs on competing imports, an undervalued currency, and access to cheap credit, labor, and land. The state’s share of investment is back to levels last reached in the late 1990s (Taplin 2019a).

Simultaneously, China’s national champions are more globally influential than ever. China’s growing technological capabilities in areas such as AI, robotics, electric vehicles, the Internet of Things, semiconductors, and quantum computing has been impressive. Chinese companies such as Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and, of course, Huawei, which earned over $107 billion dollars in revenues in 2018, now bestride the commanding heights of the digital economy and operate some of the most valuable tech platforms in the world.

This has made powerbrokers in Washington, DC nervous. While the aforementioned Chinese companies and others are suspected by US policymakers and pundits to have links with the Chinese military, spread pro-Chinese propaganda, and spy on their users, their main accusation is that Beijing is unfairly benefitting these firms while hurting American economic interests. In the words of FBI Director Christopher Ray: “Put plainly, China seems determined to steal its way up the economic ladder at our expense”. “Forced technology transfer” is the alleged source of the spectacular success of Huawei or ByteDance (the creator of TikTok) put forth by former and current Trump administration officials. China hawks such as Peter Navarro point to several episodes to bolster their case. To acquire American technology, both the Communist Party and Chinese firms alike have engaged in widespread industrial espionage; compelled American firms to enter into joint ventures that divulge trade secrets in exchange for access to the Chinese market; conducted onerous security reviews and testing requirements; and deployed trillions of dollars to acquire US companies operating in high-tech industries. Chinese companies have also attempted to acquire American technology by recruiting computer engineers and data scientists in Silicon Valley. Foreign executives who work for multinationals in China have voiced fears that “their greatest IP risk [is] theft by their own employees” (The Economist 2019).

In turn, the Trump administration has ramped up its actions against China in recent months and weeks – actions that an unnamed diplomat, cited in The Economist, termed “F*** China week” (referring to actions taken against China in 2018). This has included taxing China’s imports, restricting Chinese investment in US companies, forbidding Google and Qualcomm from doing business with Huawei, preventing Chinese students from attending US universities, and, most recently, threatening to ban TikTok.

Yet, to claim that China has attained its current level of technological capacity through IP theft misunderstands the complexity of the innovations that have fueled Sino economic growth and simply does not fit the evidence. Simply consider the case of much-maligned Huawei. As is common in the US and other Western countries, in the vast majority of lawsuits brought by MNCs against Huawei for stealing trade secrets, the parties have reached out-of-court monetary settlements or the MNCs have been awarded monetary damages (Taplin 2018). To be sure, these are not the same as an injunction issued against Huawei from selling products that use infringed upon IP. But it’s not nothing either. Also, Huawei’s R&D budget was over $15 billion dollars in 2018, fourth in the world after Google, Amazon, and Samsung (Yap and Strumpf 2019). Prior to its recent success, many of its innovations were a consequence of hiring engineers who had lost their jobs in the wake of the dot.com crash in the early 2000s (ibid)—in other words, opportunistically tapping the labor market, as good capitalists do.

In a working paper, we try to make sense of growing hand wringing over China’s technology policies and the rise of its big tech firms. We discuss different modalities of technology transfer and flesh out the efficiency and distributional considerations around the benchmark mechanism—developing countries acquiring technology from the innovation frontier via robust IP. A strong system of intellectual property rights entices and allows inventors operating in the technological core to patent their inventions in the periphery, license these to the firms located there and help the latter acquire the tacit knowledge necessary to put these inventions into practice in their unique context and circumstances.

In the paper, we broach the experiences of several Continental European countries’ technological acquisition tactics as they looked to Britain to modernize during different waves of industrialization. Among the most time-honored measures practiced by governments and firms, some of which date to the 17th Century, are: conducting industrial espionage; enticing skilled technicians to immigrate to their shores; sending their best and brightest students abroad to identify, study, and absorb the latest innovations; importing machinery; and courting FDI. A more recent conduit of international technology transfer, dating to around the Second Industrial Revolution, is individuals and firms in developing countries signing licensing agreements with foreign patent holders in exchange for royalties and other perks.

One of the countries we look at is Spain. It underwent a strong wave of trade liberalization beginning in 1959, in the wake of an acute economic crisis. Spanish firms responded to a sharp reduction in tariffs by accelerating their acquisition of foreign technology. This accompanied the licensing of intellectual property owned by inventors and firms in industrialized countries beyond Britain.

The two figures below tell the story. The first graphs Spain’s expenditures on royalties, copyrights, and licenses, versus that of Japan, France, and the Netherlands, between 1963 and 1973. It is obvious that Spain is a big outlier.

Notes: Data excludes payments for technical assistance. The denominator is the income received from abroad for royalties, copyrights, and licenses. The numerator is the expenditures on royalties paid to foreigners for royalties, copyrights, and licenses. Source: Cebrian and Lopez 2004: 134, Table 6.8.

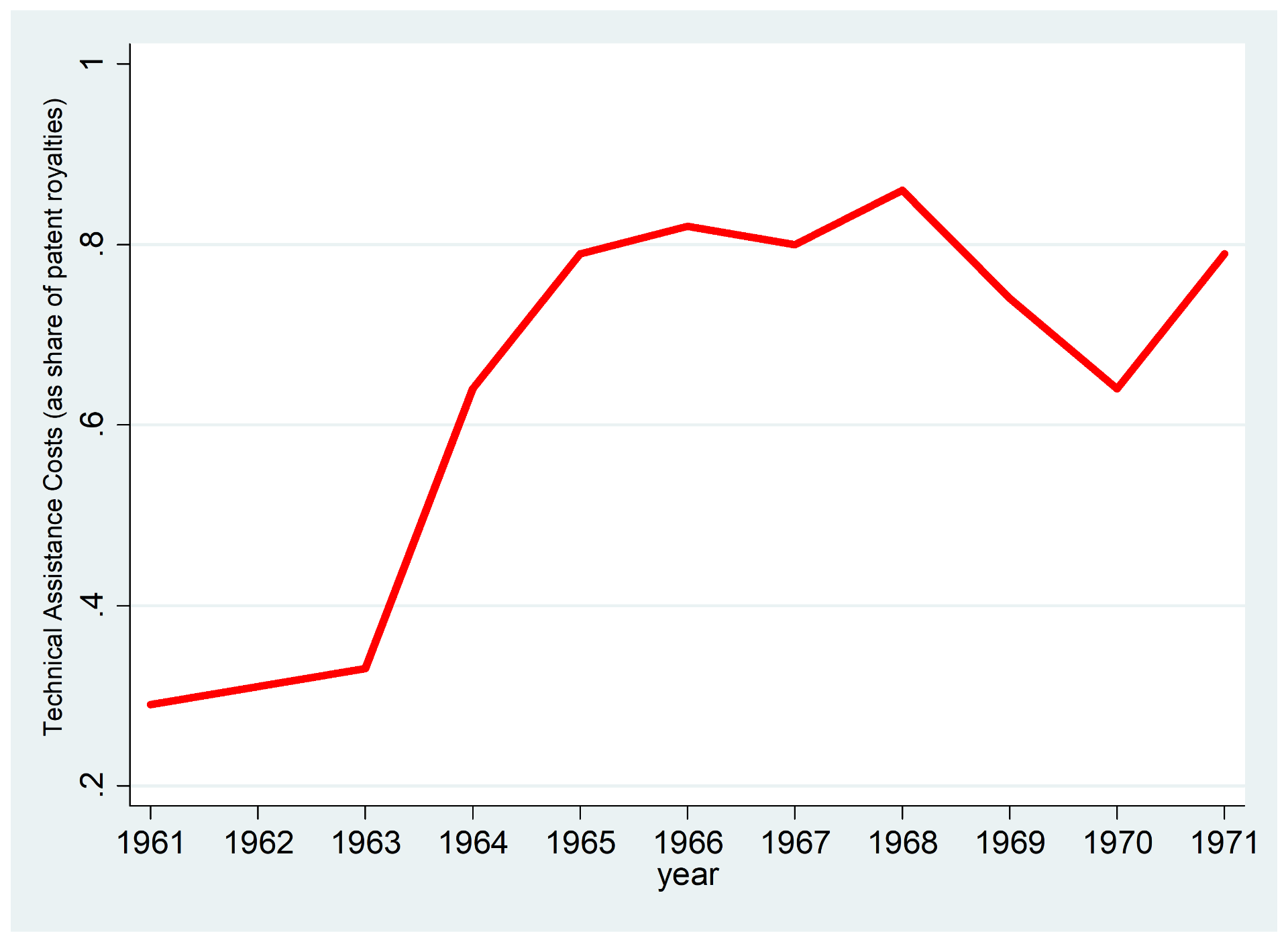

Notes: Data is aggregated from patent license contracts; the numerator is payments for administrative and technical assistance services and the denominator is total royalty payments. Source: Cebrian and Lopez 2004: 135.

The second figure graphs Spain’s technical assistance costs as a share of royalty payments on patents during roughly the same period. On the back of patent licenses paid to foreign firms, Spanish firms spent an ever-growing amount of money to acquire the know-how needed to put inventions into practice. During this time period, technical assistance payments averaged 10% of the total project costs for the firms represented in this figure; this was equivalent to 23% of their foreign exchange payments. In turn, these practices fueled the so-called Spanish miracle and allowed the country to converge with the living standards of its continental cousins.

Yet, does Spain’s experience really bear a resemblance to what is happening in China today? Make no mistake, Beijing has indeed helped Chinese firms poach engineers and scientists from Western companies, engaged in industrial espionage, undervalued its exchange rate, sheltered its domestic markets with all types of subsidies, and funneled enormous amounts of money to handpicked companies. However, we surmise that current Chinese processes are neither novel nor particularly alarming from the standpoint of economic efficiency; nor distribution, in fact: US firms doing business with China are collecting record royalty payments for their IP and generating gangbuster profits due to their access to Chinese labor, suppliers, and the country’s growing consumer market.

Indeed, in our paper we argue that technology transfer from Western companies to China is predominantly proceeding through means that are legal, agreed upon by US companies who knew what the costs and risks of joint ventures with Chinese firms entailed before entering the country, and tremendously lucrative for the former. A lot of technology transferred to Chinese companies proceeds through ordinary market mechanisms: royalties paid to US firms for patent licensing, legal imports of US machinery, and FDI that strongly benefits American firms. On the other hand, the transfer of technology to China, no matter how it occurs, helps create new companies and consumers that increase their overall demand for Western processes and products—thus also creating indirect, second-order benefits. The health of US companies doing business in and with China has proven largely impervious to Chinese IP transgressions and promises to improve further as the Chinese market continues to mature.

Plus, attempts by China to steal trade secrets or “force” technology transfer are inefficient and self-defeating. When original innovators or technology proficient firms do not have the right incentives or opportunities to also transfer the knowhow that accompanies physical and abstract technologies, the acquirer may not be able to make ready use of them. Or, supposing these innovations are eventually useful, there are high costs of theft or coercion to the acquirer: While patent licensing costs money, stealing blueprints and then trying to figure out how to put them into practice yourself is certainly not free.

What’s more, China has learned this lesson over time. China has joined all of the world’s major international IP conventions. In 2002, the Chinese government waged an extensive anti-counterfeiting and anti-piracy campaign and created additional enforcement capacity in the form of intellectual property affairs departments (Yang 2009). While in 2007 the WTO generally concurred with most of the allegations leveled by the US (see above), the resulting verdict did not force China to change its criminal prosecution thresholds for IP violations but, rather, prescribed a set of regulatory recommendations (Yang 2009). China then took steps to liberalize the individual ownership of state-funded patents, resulting in a dramatic increase in patenting activity by Chinese research and business entities—including a 488% increase in 2007 (WIPO 2009).

On the enforcement front, China has become substantially better. As Nguyen (2010) points out, especially after 2001, IP law enforcement has continuously improved and Chinese owners of intellectual property have successfully used the judicial system to enforce their rights. The total number of intellectual property cases filed in China increased from 12,205 in 2004 to 20,781 in 2007 (Nguyen 2010). Further, in discussing several cases decided by Chinese courts, “Chinese trademark owners view their trademarks as important assets in their business operations. They are not hesitant to enforce their trademark rights, they utilize judicial means to enforce their rights, and they rely on the judicial system to enjoin the alleged infringing conduct” (ibid: 806). China has also bolstered IP enforcement by eliminating pockets of judicial antipathy towards foreign IP and creating oversight bodies and regional intellectual property courts (see Weightman 2018).

Such efforts have considerably improved IP security for foreign companies. Between 2006 and 2011, for example, foreign companies brought 10% of patent infringement cases in China and won over 70% of them (Love, Helmers, and Eberhardt 2016). In 2018, injunction rates averaged around 98%, indicating that China has dramatically improved its protection of domestic and foreign IP (Weightman 2018). Indeed, consider China’s remarkable growth in its domestic innovative capacity: it has increased its global share of annual patent applications from 2% in 1997 to 44% in 2017 (WIPO 2019).

Further, contrary to conventional wisdom about China’s disrespect for IP, Chinese companies have acquired foreign technology from the US and other industrialized countries through copious patent licensing. Chinese companies operating in sectors such as transportation, energy, and robotics have paid top dollar to foreign patent holders to gain access to technology from the industrial frontier: Japanese and American firms have received billions of dollars in royalties in exchange for these licenses (Taplin 2018). In 2019, alone, China paid over $34 billion to the rest of the world for the legal use of Intellectual Property. The US accounted for roughly 23% of this amount (World Bank 2020; OECD 2020). The figure below shows that China’s royalty payments to the US grew dramatically faster than its GDP over the last two decades, echoing the substantial improvements in IP protection described above (also, see Lardy 2018). This demonstrates the extent to which US holders of IP benefit from continued Chinese economic growth—contrary to the contention made by China hawks that the country’s growth is built on opportunistic theft.

Notes: Data is normalized so that 1999 is the reference category. This graph shows that IPR payments to US entities increased 25-fold over the depicted timeframe; GDP, measured in constant 2017 international dollars, and adjusted for Purchasing Power Parity, increased roughly 5-fold. Source: World Bank and OECD.

There is just not a persuasive economic justification for the current hawkishness voiced by US policymakers about China’s trade and investment practices: that it is taking unfair advantage of the US and its companies and arrogating American technology. It instead appears motivated by US companies seeking to improve the terms of what were already pretty good deals for themselves. Were they to only focus on using the economic stick to sanction China’s human rights record and its authoritarianism, their hawkishness would be better justified.

We therefore submit that if there is a case to be made for US hawkishness vis-à-vis China it is a narrow one animated by genuine national security concerns, not mercantilism. Several of the technologies privileged by the Chinese government have obvious military applications, whether or not Chinese firms actually overtake American ones when it comes to the innovations that will shape the future. Moreover, the US government and military are just as likely as private firms to use wireless networks, hardware, and software. Therefore, having sensible anti hacking strictures in place and targeting export bans to the most sensitive technology, including around radar and perhaps quantum computing, makes some sense.

Of course, the US government is within its rights to use—or threaten to deploy—economic weapons to punish Beijing for its deteriorating human rights record and increasing authoritarianism. But that does not seem to entail blanket export bans or bans on inbound Chinese investment. Nor does it call on kicking Chinese students out of American universities or research labs without due process.

This is a very timely topic and is in the shadow of a very heated debate about US foreign policy towards China. While increasing hawkishness towards China is articulated by policymakers and pundits in the language of national security, the debate revolves around issues of technology and microeconomics that are technical in nature. Therefore, it behooves interested audiences to properly understand the details and history behind technology transfer, both in general and in the Chinese case. We firmly believe that our paper will help move the debate forward by providing much-needed light where, hitherto, there has been too much heat.

For the works cited click here