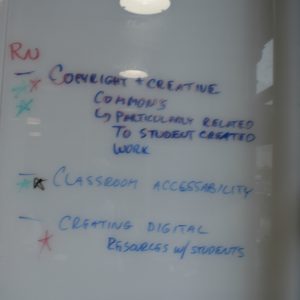

On March 26, 2018, we held the first meeting of the Using Digital Humanities in the Classroom reading group. At the beginning of the meeting, we each wrote three topics we would like to discuss, then circled around and starred 1-2 topics on each other’s lists. Here are the notes from that activity:

Tools Discussed

During the conversation that followed, several tools were mentioned, and in each blog post, I’d like to note these so we might start a list of the different technologies being used:

- WeVideo – Used in classes to make digital stories

- Fold.cm – An alternative to PowerPoint, students are able to use this make multimedia presentations.

- StoryMapJS – An easy to use tool for creating interactive maps.

Key Points

Defining Digital Humanities/Digital Scholarship

The discussion leader (Justin) raised questions about the value of starting all conversations with definitions of digital humanities and/or digital scholarship. The group found the book’s definition helpful for framing the conversation:

“We see DH not as an exclusive or unified discipline, but rather as a constellation of practical ideas, technologies, and tools that can be incorporated in a modular fashion into your own classroom practice.”1

Some of the participants recognized that definitions become important when articulating the scope of research or teaching practice to internal or external audiences, but some have struggled with overly narrow definitions of digital humanities. Ultimately, the group appreciated the emphasis on learning goals:

“Rather than engaging with new tools for their own sake, we recommend that you ground all your experiments and exercises in course content. This will allow you to design you course carefully, on a case-by-case basis, so that particular exercises are suited to the particular course topic or text.” 2

Resistance vs. challenges

The conversation gained momentum around the book’s “Presumption of resistance” and went on to explore a number of related topics. Initially, several in the group critiqued the the way that Chapter 1 assumed varying kinds of resistance to digital humanities techniques. Generally, the faculty members present felt supported in their experiments with DH practices and that students were generally receptive to these approaches.

As the conversation progressed, however, the group began to recognize that there are some real challenges to potentially working in this area at UW Tacoma:

Extreme range of digital literacies and skills among students: Instructors experience a wide spectrum of digital abilities and aptitudes among students. Many students are “digital natives” and are well-versed in the rhetorical approaches used in this media rich environment, but most have experienced the digital realm as consumers rather than critically-engaged learners and creators. Some might even struggle with commonly-used technologies, such as Word or PowerPoint, while others may take to it quickly. Finding a middle ground can be quite challenging.3

Student access to technology: One professor present has surveyed his students access to and ownership of technology. Although we didn’t have the precise numbers, he found that while most UW Tacoma students have smartphones, a sizeable percentage do not have access to the internet at home and may not own a computer. Flowing from these observations, someone observed that for assignments that require a lot of technology: “Whatever we do has to be on campus and in the classroom?”4

Recognizing failure and frustration as part of learning: Several present had backgrounds in design and recognized failure as part of the design process, but translating this approach to the classroom, technology-related assignments, and assessment can pose some difficulties. Students experience a lot of anxiety if they don’t know technology required for the assignment. Compounding the problems, instructors may not want to sacrifice classroom time for learning associated technology. One response has been to use low stakes assignments to establish a baseline of skills and then evaluate the students on growth. Another possibility is assigning reflective pieces about the process.5

Topics we would have discussed if we had more time

Possible workshops or training or workshops could be built around the following topics:

- Universal Design: There was an overwhelming interest in UD, but many present felt that they would need additional training and support to integrate this.

- Digital Public Library of America: Many were drawn to this as a resource and would like to investigate how to better integrate into courses.

- Thinking through implications of publicly-shared student work: Many classes that are creating alternative assignments are producing work that worthy of sharing with a wider audience, but several questions about permissions, student privacy, and digital repository structure remain.

- Creative Commons and copyright in general: Working in the digital environment raises a host of copyright questions, and many wanted to learn more about how to navigate these questions.

- Battershill & Ross, 2. Another helpful quote: “For us, digital humanities simply represents a community of scholars and teachers interested in using or studying technology. We use humanities technologies to study digital cultures, tools, and concepts, and we also use computational methods to explore the traditional objects of humanistic inquiry.” ↩

- Battershill & Ross, 4 ↩

- Many of the later sections actually explore this issue, especially Chapters 5 & 6 on designing and managing classroom activities, but at this early stage, we appreciated the emphasis Battershill and Ross placed on learning goals. ↩

- Battershill & Ross discuss similar issues in the section “Privacy, safety, and account management” (52-67), but the entire Chapter 3 “Ensuring Accessibility” explores related themes. ↩

- See Battershill and Ross, “Your students resistance,” (19-21) for a related discussion. ↩