In the best case scenario the students will leave the course, not with answers, but with more questions, and even more importantly, the capacity to ask still more questions generated from their continual pursuit and practice of the subjectivities we hope to inspire. — Michael Wesch, quoted on p. 123 of Battershill & Ross, Using Digital Humanities in the Classroom)

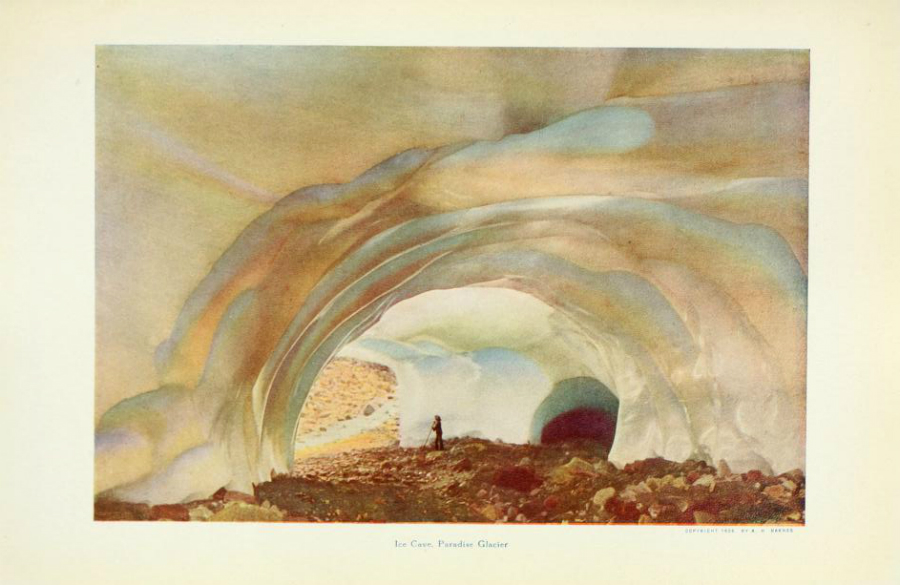

Ever since I first saw them, the strange, disorienting photographs of tourists and climbers venturing into ice tunnels on Tahoma (aka Mt. Rainier) have always appealed to me, and I include one here because it seems a good a place as any to begin this summary of our exploration of the practical aspects of integrating digital humanities practices in the classroom at UW Tacoma.

Tools Discussed

As always, I like to pull together a quick list of the digital tools raised during our conversation:

- PowerPoint (and slide presentation software, in general) – Mentioned mostly in a critical way as the default form of presenting information.

- Tumblr – An alternative form for sharing class information, one faculty used it at other intitution.

- Google Books Ngram Viewer – Mines texts in Google books to show the instances of certain words.

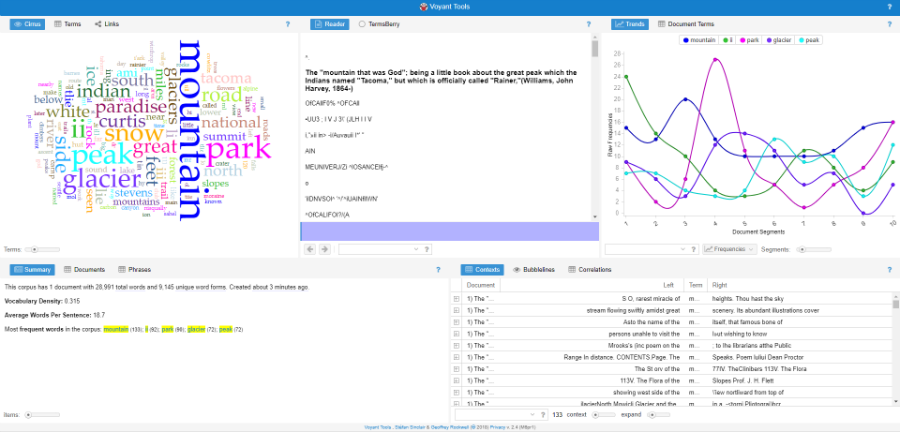

- Voyant – A text visualization software program that allows visualizing and analyzing text.

- Juxta – Software program that enables comparison multiple versions of text.

Playing with a Tool: Voyant

Expanding on the use of tools, I wanted to show what it can look like when you take text and put into Voyant. For this sample, I used a public domain text called The Mountain that was God by John William Harvey1.

Summary of Summary of Book Discussion

OK, let’s get to business. We met in April to discuss chapters 4-8 of “Using Digital Humanities in the Classroom” by Battershill and Ross. This section of the book presents a kind of “life cycle” overview of how digital humanities might be incorporated into the classroom, demonstrating how instructors can structure their courses around engagement with digital technologies and resources. In the summaries below, I pull key points raised during the conversation.

Chapter 4: Designing Syllabi – Randy Nichols (blog post)

Randy began by expressing his discomfort with presentation slides, which was why he wrote a blog post. This opened up a conversation around the ways that technology can inadvertently shape expectations and convey certain unintended values. One person mentioned how having presentation slides can give the illusion of being organized. 2

Other technologies seem to enable collaboration and do not limit the ways students might interact with it. For instance, in the past Randy has used Tumblr for his classes.

This raised questions about how technology might inadvertently shape learning objectives, rather than be the source of students interactions with technology, as Battershill and Ross suggest. Instructors’ time and comfort level with new technologies can influence their adoption. It seems that one way around these issues might be to approach the development of learning objectives as an iterative process that developed in relationship to technology.

Another important strand of our conversation touched on setting clear expectations about online behavior.

Chapter 5: Designing Classroom Activities – Libi Sunderman (Google Slides; login required)

Libi was really engaged with this chapter and offered a tour of the tools that it exposed her to. In her slides, she investigates the tools that seemed relevant to her. Generally, she favored tools that are easy and don’t take a lot time to figure out. As a historian, she seemed to prefer tools that analyze differences in texts. She did ask some questions about how she would engage students with the tools beyond just looking at them.

Since visiting archives and libraries and exposing students to primary sources is a key part of her work, she has also found virtual tours of collections to be useful and has done this with the Tacoma Historical Society.

Chapter 6: Managing Classroom Activities – Rebecca Disrud (Google Slides; login required)

Rebecca felt that this chapter was mistitled and thought it should be called “Troubleshooting Technology.” The solution could be summed up with a single word: “practice,” so that you can avoid most of the typical problems. Many in the group generally felt the most helpful suggestions were to design the course into module units that could be adjusted if needed.

A key point that resonated: Battershill and Ross emphasize that total technological failure can turn into a valuable teaching moment.

Mention of the Inspiration Lab at Vancouver Public Library was of particular interest. It is space with a variety of technologies and digital tools that enable visitors to create new works.

“The “inspiration lab,” for example, is open to university groups as well as to the public, and often, students can do more than use the equipment: they can participate through lab-based activities that start in the classroom in the broader creative and critical digital activities happening in their own communities.” (Battershill & Ross, p. 103)

A group on campus is looking at developing maker/tinkerspace, as well as a Learning Commons. We recognized that a space where faculty could practice and receive support would be welcome on campus. Right now, this happens in a variety of places and tends to be scoped to particular technologies.

Chapter 7: Creating Digital Assignments – Nicole Blaire (Google Slides; login required)

Nicole wasn’t able to make it but her slides pull out the key points. I particularly liked the points that she highlighted from Battershill and Ross as principles/best practices:

- Require short reflection papers for graded work that use new digital skills.

- Limit your students to one new tool or platform per assignment.

- Be flexible: adapt to student needs but have a clear rubric and set of expectations.

- Digital assignments do not need to be overly complex: public writing, such as a public blog, “is at the very heart of the digital humanities.”

Chapter 8: Evaluating Student Work – Alex Miller (Google Doc; login required)

Alex presented this chapter; he found it to be consistent with the rest of the book in the ways that offered methods of encouraging experimentation by student and incorporating the possibility of failure into assignments. He felt that a key point was to move beyond “being good with computers” or achieving mastery. Measuring progress and competency seem like better measures.

Drawing from his experience, as well as the reading, the group felt that getting students involved in the evaluation and partnering with them to create rubrics can set these expectations. Other options are to offer classes pass/fail and using in-take surveys to evaluate the students.

Yet there were questions around:

- How do you evaluate risk and effort? How do you encourage and assess risk?

Alex offered the assignment description and rubric that he uses when assigning students to create digital videos in his “Intro to Masculinities” class:

- Published in 1911, this book is now in the public domain and available in the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/mountainthatwa00will. ↩

- At its worst, slides can misrepresent information, as Edward Tufte aptly expressed it in his critique “The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint”. ↩