…digital media technologies are changing the structure of the habits of being a scholar (Daniels & Thistlethwaite, 2016, p. 93).

I have thoroughly enjoyed the ideas that eddied around me during our discussions, yet as I listened to this week’s discussion about the possible effect of digital technologies on publication practices or tenure and promotion, I was acutely aware my viewpoint within the dialogue was different than the rest of those at the table.

I am not faculty considering how to include or increase my use of digital tools or technologies in my classroom—or wondering if my scholarly work will become somehow devalued in an increasingly digital world.

Neither am I a librarian peering into the future of information embedded in digital practices, watching the cost of scholarly journals rise every year and wondering how to best help students gain access to technology, costly textbooks, or other course necessities that might be beyond their current technological expertise or financial means.

From my position as a writing instructor in the TLC, I see some students struggle with learning unfamiliar technologies, and recognize the difficulties others face in completing assignments when they cannot afford course texts. I am daily aware of their unfamiliarity of some with academic practices that increasingly require a digital literacy beyond their understanding. The tools of the academy are changing, even if the work is not.

Yet, in considering how to respond to the three chapters discussed this week, I realize I sit most comfortably in the position of student. I am here in this room to learn, to glean what I can from a discussion with those who understand a side of this topic with which I have little experience. But there is a viewpoint I do understand.

As a current doctoral student, I am the scholar being trained in a digital era. I am the student who was just given a book list priced at nearly $300 for (used) books for one course. Yet, as that scholar-in-training, I also can’t help but wonder in what ways the acceptance and use of digital technologies will come to affect the scholarship of the future—including my own.

Open access is, above all things, a moral and political decision (Jiménez et al., 2015, para. 2; cited in Daniels and Thistlethwaite, 2016, p. 79).

Through both my positions—student and staff—I have become a firm believer in the power of open access and digital technologies to spread the influence of the academy: its scholarship reaching out from behind ivy-covered walls and extending knowledge toward those who have long been kept at a distance, whether because of a paywall or a lack of accessible language. I believe that making the work of scholars available to a larger public sphere is, quite simply, a matter of social justice—a “human right,” if you will. And I agree with authors Jessie Daniels and Polly Thistlethwaite (2016) as they remind us: there is nothing important that cannot [somehow] be made interesting to a more “general reader” (p. 97).

You never know who will benefit from your work. The only way to find out is to make it accessible (“Interview” with Sarah Kendizor in Tadween Editors, 2013; cited in Daniels & Thistlethwaite, 2016, p. 63).

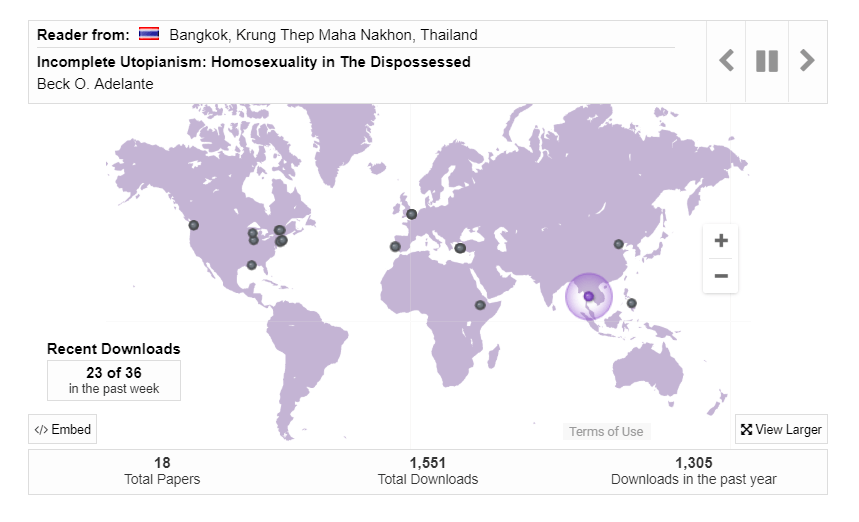

Although the shift to digital scholarship may be slow in coming, it is coming. Faculty across this campus—and many others—are already a part of the change, whether through teaching digital storytelling techniques, using digital tools in teaching, or creating digital portfolios and projects with their students. Many are already including ebooks or open access materials in their course syllabi and have long taught their students the value of moving beyond a simple Google search to recognizing scholarly sources, such as journals or databases housed in the library and available 24/7. They might even be encouraging their students to submit their work to open-access journals like Access: Interdisciplinary Journal of Student Research and Scholarship with its 1500+ downloads of 16 student papers—in just over a year.

Access, housed in the UW Tacoma Digital Commons and networked throughout other commons sites across the web and around the world, was created to expand the reach of students’ scholarly work. I’m admittedly proud of Access’ reach, but an even better example of the scope of open-access sites like Digital Commons can be seen in a single paper: “Corporate Social Responsibility of Multinational Corporations” (Chan, 2014), UW Tacoma’s most popular paper, downloaded more than 31,000 times around the globe in just over three years.

Digital media technologies provide a tremendous opportunity for the scholarship of engagement (Daniels & Thistlethwaite, 2016, p. 106).

For faculty on an urban-serving campus like ours, there is undoubtedly a certain tension surrounding an individual desire to participate in digital practices that would inform our communities and engage them in our scholarship and an uncertainty

Still, the opportunity is in our hands to discover just where the road into digital scholarship might lead.

Jimenez, A.C., Boyer, D., Hartigan, J., & de la Cadena, M. (2015). Open access: A collective ecology for AAA publishing in the digital age – Cultural Anthropology [website]. Retrieved from www.culanth.org/fieldsights/684-open-acess-a-collective-ecology-for-aaaq-publishing-in-the-digital-age.