Digital Scholarship, like legacy scholarship, refers to a set of practices rather than a single field of study. (Jessie Daniels and Polly Thistlethwaite, Being a Scholar in a Digital Era, 8)

We held our first discussion of Being a Scholar in a Digital Era by Jessie Daniels and Polly Thistlethwaite on October 8, 2018. This was at the beginning the quarter, and I’m just now catching up on the notes I took during that meeting.

We met in the Chihuly Room, so named for the Chinook Red Chandelier by Dale Chihuly that hangs there, and the space soon filled up with faculty and librarians. All ten seats at the table were taken, and we had to pull in chairs from downstairs. People also took some of the comfortable chairs around the room. I forgot to count how many people were present, but I estimate about eighteen because we had some drop-in participants.

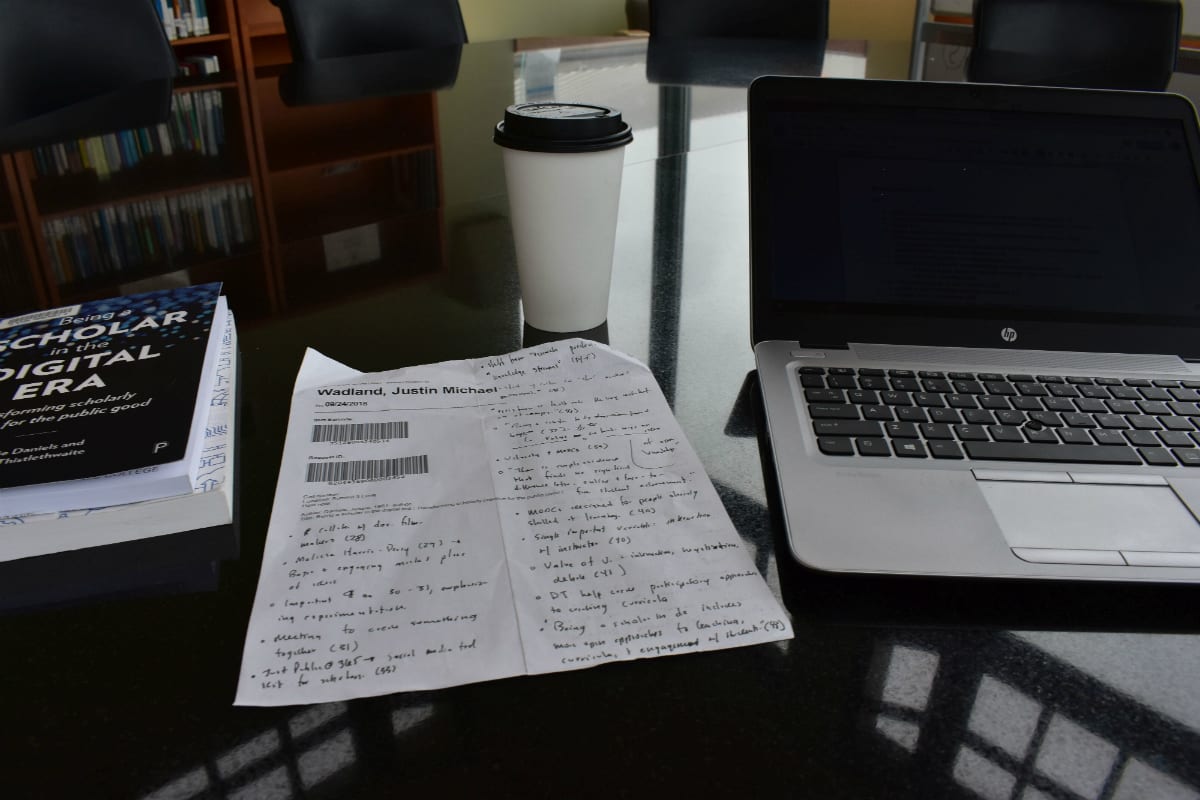

To start the conversation, I closed my computer and opened a notebook I started earlier this year to track conversations I’m having around digital scholarship. It was a wild ride once we started talking about the first three chapters of Being a Scholar in a Digital Era. Two people had signed up for each chapter, and I asked each person to provide a brief response and pose one question to the group. My intention was to do a kind of round robin or survey of people’s responses, but there was such energy around certain topics that people couldn’t keep from responding the questions.

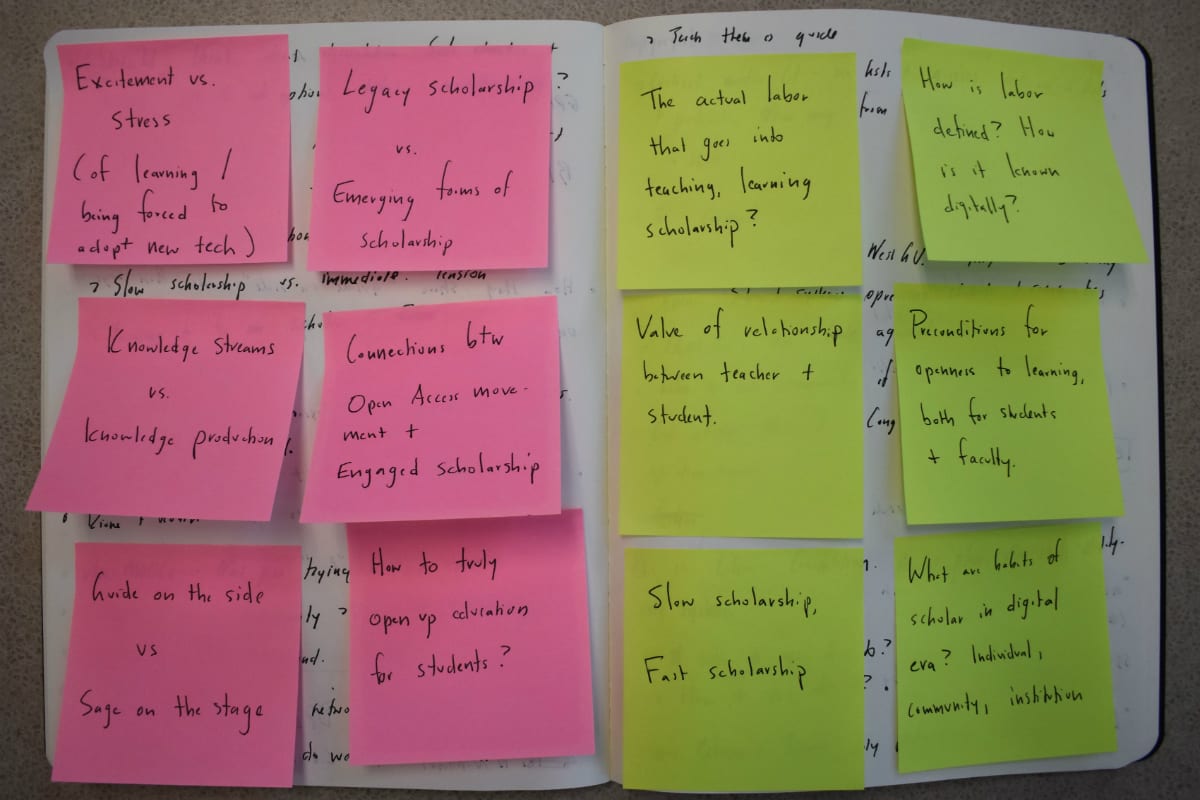

Here are just a few that I heard and jotted down:

- How does one transition from being a “sage on the stage to a guide on the side”?

- What is the overlap between engaged scholarship and open access? (This was my own.)

- How do we effectively teach in a networked environment? How do we effectively shift to open models?

- What is the actual labor that goes into teach, learning, and scholarship? How do we account for the disruptions, blurring of boundaries, and expansion of labor that technology of creates?

I felt like I was in eye of an intellectual cyclone circling around that room, drawing its power from everyone’s curiosity and uncertainty, their questions and attempts at solutions, their excitement and anxiety. My brain went into facilitation mode and focused more on keeping the conversation on track and making sure everyone’s perspective was heard. Thus, I was more focused on the present than on remembering. Yet somehow my hand kept moving. Here are the messy notes I took that day:

I show these notes because they are evidence of one approaches I bring to the “craft” of digital scholarship. As a member of Generation X, my life and education has straddled analog and digital worlds, and this background has informed many of the practices I use to navigate and understand digital scholarship. Perhaps this is why I was so drawn to the discussion of the “craft” of digital scholarship mentioned in Being a Scholar in a Digital Era.

In the appendix to his classic The Sociological Imagination, titled ‘On intellectual craftsmanship’, C. Wright Mills exhorts aspiring scholars to keep a journal and create a ‘filing system’ to reflect on personal experiences, notes about the literature in one’s field, along with charts and diagrams. In this appendix, Mills refers to being a scholar as ‘a choice of how to live,’ he says, ‘as well as a choice of career’. It is, he explains, about being a scholar, ‘a structure of habits’ (Mills, 1959). (Daniels and Thislthwaite, 10)

The next five pages (pp. 11-14) of Being a Scholar in the Digital Era then go on to recount the many, many changes that have transformed scholarship, scholarly communication, and the distribution of knowledge. In sum, “The ever-changing pastiche of digital technologies, alongside the analog of occasional in-person meetings, enables a new level of connectedness among scholars across geographic distance and types of institutions. Sharing research interests and exchanging work among scholars has never been easier.” (14)

Rather than digging into the specific changes (which is the purpose of this reading circle), I would like to stay awhile on the idea of craft because it reminds me of observations in another book I read recently: David Levy’s Mindful Tech: How to Bring to Our Digital Lives. In this text, Levy develops a notion that our interactions with digital, online technologies can become a kind of craft:

When I suggest we think of our online activity as a craft, I mean to call attention to the skill involved. But I also mean to highlight three addition dimensions of craftwork, making four in all: intention, care, skill, and learning. (David Levy, Mindful Tech, 7)

Levy’s book then investigates how personal practice shapes our digital identities (whether personal or professional) and offers a series of activities that enable readers to develop their own sense of digital craft. I don’t have space to explore his ideas thoroughly, but I am realizing that one of the core ways that I have cultivated my own sense “digital craft” has been to deliberately blend it with the analog. I often seek out and create spaces for reflection away from the screen and humming hard drive so that I might recognize more awareness along the dimensions Levy develops. One of these is with a notebook.

These observations are all highly personal, but so are habits–or practices. Taking this a step further, I see my role as an educator-librarian is to also encourage and support the digital craft of others. Yet, how do I do this in a meaningful way? This book group is one example. A few days ago, I took what I’ve heard and tried to distill it. On the left are themes (pink), and on the right issues of practice (yellow).