Post by: julia Cheresh, Katlyn Fuentes & gina pak, undergraduates in biology, aquatic and fishery sciences, and environmental studies, respectively

Though scientific research has rapidly advanced our foundational understanding of fisheries – and provided us new tools to study them – these advances have often not considered social implications when implementing or designing policies for sustainable fisheries. This glaring disconnect between natural and social sciences leaves researchers potentially asking the wrong questions, and lawmakers creating policies that aren’t as relevant as they could be.

How can we incorporate social considerations into fisheries science and management?

Dr. Christina Hicks, an Environmental Social Scientist at Lancaster University, has made it her mission to study how the relationships between individuals, societies, and the environment impact not only nature, but also human well-being. Her research focuses on small-scale fisheries undergoing changes in both the environment and the society where they occur, and addresses three main themes: 1) guaranteeing social and ecological sustainability, and access to fisheries nutrition, 2) integrating social theory into research on ecosystem services, and 3) building the capacity of fisheries governance.

Some of Dr. Hicks’ suggestions…

Socially Sensitive Fisheries

Traditionally, a large gap has separated the fields of natural and social sciences. While there has been a push for fisheries scientists to engage more with culture and society in ways that generate meaningful and relevant policies, we are still falling short of doing this successfully in many cases.

“I think there is a much greater recognition of the importance of engaging with the human dimension. I think people are still struggling to understand how to do that, and how to translate what we’ve been traditionally doing within fisheries science to this very complex, messy social domain, and how that can translate into effective policy.” – Dr. Christina Hicks

Dr. Hicks attributes this lack of translation to a few factors, including the absence of effective communication between natural and social scientists, and no common language. The two fields operate in very different ways, and the thought processes used to tackle problems within them are vastly different. We are therefore “interdisciplinarily illiterate”, says Dr. Hicks. Social scientists have a difficult time understanding publications in natural science, and vice versa. To effectively communicate across these disciplines, Dr. Hicks asserts that those in each field don’t need an extensive education in the opposing field, but a basic literacy, gained even in a single class, could improve the ways in which the fields interact.

Nutritionally Sensitive Fisheries

Social and natural sciences can also produce better results when cooperatively working together to solve relevant issues. It’s important to determine the ways that different societies benefit from an ecosystem – which are often rooted in the values each community collectively prioritizes. These factors may be social or cultural relations, economics, or even environmental sustainability, to name a few. Looking at what certain societies prioritize can help maximize the benefits they can receive from a fishery, as well as improve access to these benefits. Therefore, we need to better understand how people negotiate these different mechanisms of access. An example of this can be seen by looking at nutrition-sensitive fisheries in East Africa.

“Islands of Failure, in a Sea of Hope”

In East Africa, Dr. Hicks has spent many years researching the societal dynamics of local communities and how they work with their natural environment. Villages in East Africa depend on fish, and fisheries provide individual-level benefits through nutrition and market value, as well as a sense of identity to the people.

During her time in coastal East Africa, Dr. Hicks has found that though these communities eat two times fewer fish than we do in the US, the nutritional benefits they reap from these fishes are twice as much compared to those here. However, despite their predominately pescetarian diet being more nutritional than a US diet, there is a significant micronutrient deficiency in the fishes consumed in East Africa. Which begs the question:

Can nutritional needs be met through marine fisheries?

For areas with high nutritional yield and significant micronutrient deficiency (such as those in East Africa), the answer is yes.

By looking at global patterns of nutritional yield and identifying nutritional “hot-spots”, we can work to solve social problems related to nutrition. These “islands of hope” can potentially meet individuals’ nutritional needs by comparing nutritional yields of the fishes nearby and identifying the social drivers of exploitation (trade policies, international markets) and what helps mediate access to these benefits.

Why We Should Care

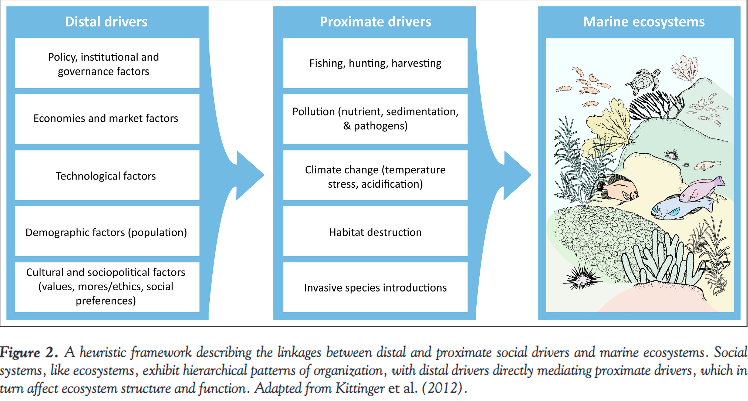

When the lines of communication between the fields of natural and social sciences grow stronger, the benefits will be enormous. In a recently published paper, Dr. Hicks and her colleagues discuss the potential for social factors to serve as indicators that precede and warn of coming ecological regime shifts (Hicks et al. 2016a). Think of this scenario: a fishery is subject to overfishing, which causes a regime shift in the structure of the food web. One could focus on the mechanisms of overfishing, or the proximate cause (for example, fleet overcapacity). But if we instead seek to understand what drove overfishing – the distal driver – we could better predict and prevent future regime shifts. In this scenario, population growth, market demand, or new technologies could have all been distal drivers leading to overfishing. Once a regime shift is set in motion, it is very difficult to stop – making it even more important to prevent these shifts from occurring in the first place.

In a separate paper, Dr. Hicks states that “social indicators” are factors that are important to a given society and can be tracked to ensure accountability toward normative environmental sustainability goals (Hicks et al. 2016b). She suggests that monitoring social drivers, such as the opening of new markets, governance changes, or population growth, in combination with tracking social indicators, such as human well-being, agency, and inequality, will help predict environmental changes and ensure sustainability goals are achieved.

What does this mean for you?

We can start by trying to understand and eradicate barriers in communication between natural and social sciences, to manage resources in a more sustainable manner.

So let’s start talking more with social scientists and putting more effort into interdisciplinary communication and research.

References and Further Reading:

For more information on breaching the barriers between science and public communication, check out the blog post: We need to talk: Relationship tips for science and policy.

Hicks CC, Crowder LB, Graham NA, Kittinger JN, Cornu EL (2016a) Social drivers forewarn of marine regime shifts. Front Ecol Environ 14:252–260

Hicks CC, Levine A, Agrawal A, Basurto X, Breslow SJ, Carothers C, Charnley S, Coulthard S, Dolsak N, Donatuto J, Garcia-Quijano C, Mascia MB, Norman K, Poe MR, Satterfield T, Martin KS, Levin PS (2016b) Engage key social concepts for sustainability. Science 352:38–40

Leave a Reply