BY sarah yerrace, AQUATIC AND FISHERY SCIENCES UNDERGRADUATE, and brittany pringle & kienan valdez, biology undergraduates

Let’s consider a hypothetical situation where you live along the coast and depend on fish for most of your daily protein, omega-3 fatty acids, and essential micronutrients. But the fish at the market is becoming too expensive, your food supply is running short due to climate change, and your family’s health is in jeopardy. This hypothetical situation may be somewhat abstract to most of us living in the US, but it is a crooked reality for the 1.4 billion people worldwide who are dependent on fish and vulnerable to such nutritional deficiencies.

Climate change, the Paris Agreement, and fisheries

The global population is projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 and, if current trends stay constant, over one billion people will directly or indirectly rely on fisheries for their livelihood. An additional three billion people will be reliant on fish for their daily protein (Lam et al., 2016). Dr. William Cheung, an Associate Professor and Director of Science of the Nippon Foundation-UBC Nereus Program at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, University of British Columbia, has studied climate change and fisheries, including how meeting the Paris Agreement could help fisheries and those reliant on fish. The Paris Agreement is a global agreement within the United Nations Framework convention on Climate Change that aims to limit global temperature rise below 1.5°C relative to preindustrial temperatures.

Money (and fish) down the drain

As the oceans warm, ecosystems are affected in several ways. Species shift their distributions: they may shrink, expand, or move altogether. Most species move towards the poles or move into deeper, cooler waters if their habitats get too warm. Fishes are currently moving 3 meters deeper per decade (Sumaila et al., 2011) and towards the poles at 10-18 kilometers per decade (Weatherdon et al., 2016). This means fishermen have to travel farther to catch fish, increasing costs and decreasing profit.

Currently, global annual fish catch is estimated to be about 130 million tons (Lam et al., 2016). However, with each 1°C increase in temperature, fish catches will likely decrease by more than 3 million tons (Cheung et al., 2016). Under a “business-as-usual” scenario, this could translate to roughly 10 million tons of lost fish catch, not to mention significant revenue losses.

In addition to changes in fish distributions, catch composition is expected to change. Researchers are estimating an increase in the relative abundance of low-value fish species, further reducing profits for fishermen already economically stressed. This could lead to a 35% loss in global fisheries revenue (Lam et al., 2016).

Getting kicked while they’re down

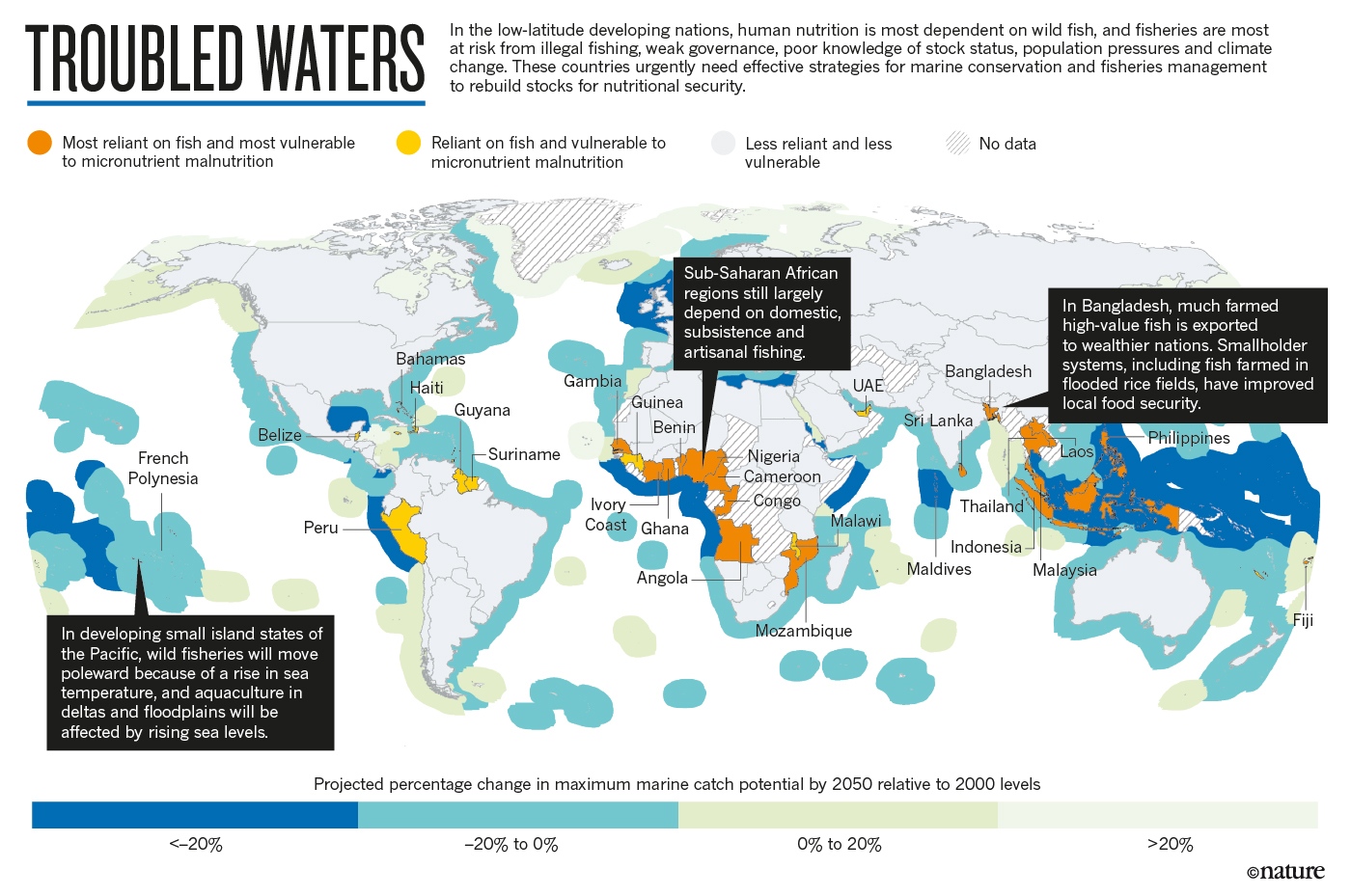

The effects of climate change on fisheries are not felt equally across the globe and the people who will feel the effects the strongest are also those who have the fewest resources to deal with such changes.

Tropical areas are home to coastal communities that rely on fishing for both income and nutrition. Developing nations often turn to fishing because they have few or no economic or agricultural alternatives. Developed nations like the USA, on the other hand, have numerous sources of income and food. Developed nations can compensate for nutritional losses in fisheries with increased agriculture, imports, supplements like vitamins, and eating other fortified foods. Small communities in developing nations don’t have these luxuries. As fishes move away from the equator, these subsistence fishing communities will be the first to lose out on catches. The fish will get smaller too; warmer temperatures increase fish metabolism but warm water holds less oxygen, leading to smaller body size and a 20% decrease in the biomass of fish communities (Golden et al., 2016). With fewer and smaller fish to eat, micronutrient deficiencies will increase risks of perinatal and maternal mortality, growth retardation, child mortality, cognitive deficits, and reduced immune function (Black et al., 2013).

What is the world to do?

Awareness, approaches, and action. Sounds simple, right? Not really. But according to Dr. Cheung, there are a few ways that fisheries and society can respond to the impacts of climate change:

Figure 1. The four action options: Protect, Mitigate, Repair, Adapt. Reducing CO₂ emissions is in bold because it directly addresses the problem of climate change and is seen by most as the only true ‘solution’. Mitigation is reducing the severity of warming. Adaptation is changing our behavior to live with the consequences of warming. All options except mitigation become less effective with increasing CO₂. From Gattuso et al., 2015

1) Global mitigation

As carbon in the atmosphere continues to increase, adaptation, protection, and repairs become less effective. Mitigation is the best way to help fisheries because it addresses warming at the source: carbon emissions (See Fig. 1)

2) Achieve the Paris Agreement’s target

Meeting the 1.5° C requirement will reduce fish species turnover (Cheung et al. 2016), which will generate more predictable revenue and food availability.

3) Minimize the impacts on the ocean

There must be rapid reductions in CO₂ emissions so that the ocean can adapt and marine organisms, ecosystems, and human health can be effectively protected (Gattuso et al. 2015).

4) Reform aquaculture

Aquaculture is an essential alternative to fisheries for undernourished people. Aquaculture can provide a consistent supply of fish more efficiently than other forms of agriculture including cattle or pork, and could boost the local economy by providing income and employment. But it needs reform. Less intensive and domestic production of cheap and nutritious species should be a goal, along with provisioning coastal resource rights to small-scale aquaculture projects that ensure local communities benefit.

For fisheries sustainability, don’t ignore climate change

If you care about sustainable fishing, you cannot ignore climate change. The US’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement greatly worried many scientists including Dr. Cheung. But “this created a strong active response from the US and many other countries to prevent or reduce carbon emissions. Risk of taking action is lower” he says. Taking initiative on climate change will not only create a healthier, happier world, it will address many issues faced by fisheries and fishing communities.

Collective efforts play a big role

It may seem impossible for an individual like yourself to make a difference, but you are very powerful when it comes to your vote. Dr. Cheung says “vote for people who support taking action on climate change. Collective efforts play a big role in change. Habitat protection can help reduce climate change effects.” Also, make sure to follow trusted scientific news sites and engage with local people who are directly involved in this issue.

Vote for people who support taking action on climate change.

-Dr. William Cheung

Now, imagine that it is the year 2050 and appropriate actions were taken: CO₂ emissions have been rapidly reduced, global aquaculture has been significantly reformed, and climate agreements that minimize the damages to the ocean have been implemented. You head to the coast and fish all day, catching many healthy, good-sized fish. Affordable fish are available at the market and your growing children are healthy because they have the fish and essential nutrients they require. The “crooked reality” that was feared for many equatorial coastal countries is no longer an issue, and they don’t suffer as badly from the effects of climate change.

There are over 7.5 billion humans on Earth. But our fate is not decided. Together, there is hope. A collective force can change our trajectory. It starts with you, the individual, making smart choices leading to a smaller carbon foot print.

References

Black, R. E., Victora, C. G., Walker, S. P., Bhutta, Z. A., Christian, P., De Onis, M., … & Uauy, R. (2013). Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. The lancet, 382(9890), 427-451.

Cheung, W. W., Reygondeau, G., & Frölicher, T. L. (2016). Large benefits to marine fisheries of meeting the 1.5 C global warming target. Science, 354(6319), 1591-1594.

Gattuso, J. P., Magnan, A., Billé, R., Cheung, W. W., Howes, E. L., Joos, F., … & Hoegh-Guldberg, O. (2015). Contrasting futures for ocean and society from different anthropogenic CO2 emissions scenarios. Science, 349(6243), aac4722.

Golden, C. D., Allison, E. H., Cheung, W. W., Dey, M. M., Halpern, B. S., McCauley, D. J., … & Myers, S. S. (2016). Fall in fish catch threatens human health. Nature, 534(7607), 317-320.

Lam, V. W., Cheung, W. W., Reygondeau, G., & Sumaila, U. R. (2016). Projected change in global fisheries revenues under climate change. Scientific reports, 6, 32607.

Sumaila, U. R., Cheung, W. W., Lam, V. W., Pauly, D., & Herrick, S. (2011). Climate change impacts on the biophysics and economics of world fisheries. Nature climate change, 1(9), 449.

Weatherdon, L. V., Ota, Y., Jones, M. C., Close, D. A., & Cheung, W. W. (2016). Projected scenarios for coastal First Nations’ fisheries catch potential under climate change: management challenges and opportunities. PloS one, 11(1), e0145285.

NOAA. “What Is Aquaculture?” National Ocean Service, 21 Feb. 2018, oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/aquaculture.html.

Leave a Reply