There is a joy in settling down to read a special newspaper or magazine article, one where you know the writer is cataloging the unordinary. Something about an everyday medium that normally covers topics and records events we consider commonplace (sports, politics, violent crimes, etc.) instead chronicling astonishment and intrigue is uniquely appealing—perhaps because it reminds us that the world is not constantly a cold, dull place. Two of my favorite examples of these are “The ballad of the Chowchilla bus kidnapping,” which recounts the hijacking of a school bus and the nationwide fervor that followed, and “Pellet Ice is the Good Ice,” which takes a deep dive into a kind of ice cube that’s hard to come by and unrivaled in quality.

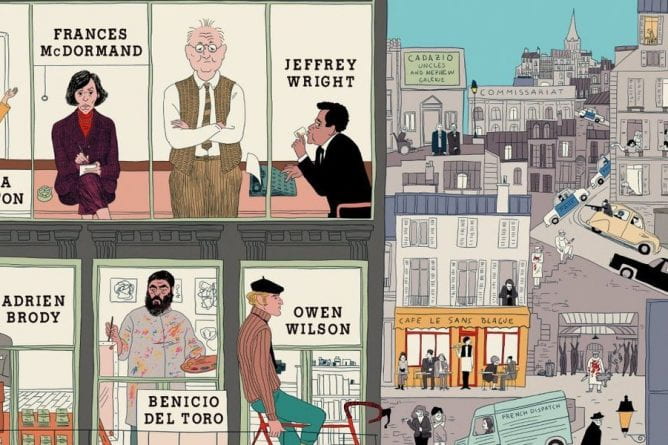

The French Dispatch is a love letter to stories like these, recounting the last publication of a magazine based in the fictional French city of Ennui-sur-Blasé after the death of its editor-in-chief (played by Bill Murray). It primarily focuses on the writing of three of the outfit’s distinguished writers: Berensen (Tilda Swinton) narrates the journey of soul-searching and unrequited love that an imprisoned artist (Benicio del Toro) embarks upon, Krementz (Frances McDormand) follows a youth rebellion alongside a budding student (Timothée Chalamet), and Wright (Jeffrey Wright, the character and the actor sharing their last names) recalls how, in the course of going to interview a police chef (Stephen Park), he became tangled in a hostage situation. The bicycle-riding writer Sazerac (Owen Wilson) opens the film by giving a portrait of Ennui, exploring how the brightest and darkest parts of this film’s backdrop have changed over time.

It makes sense that after The Grand Budapest Hotel, a movie that combines narration and editing to convey the experience of reading a book cinematically, Anderson would attempt to weave prose and visuals again. This time there’s multiple authorial voices in the mix, and each story has a different framing device within the film’s larger one. The intercutting back and forth as events of different timelines are woven together reminds the audience that they are not just watching these stories unfold—they are listening to their retelling. Knowing that there’s someone there to guide you through these partly absurd, sometimes harrowing spectacles provides a sense of familiarity where The French Dispatch might otherwise be unintentionally alienating.

Like all Anderson movies, even those from before he was obsessing over precise cinematography and commanding budgets in the millions, The French Dispatch is beautiful to watch at any given moment. Even the shots that require less organization and choreography still feel exquisitely handcrafted, like a play. The French Dispatch also makes ample use of contrasting color scenes with black and white, something Anderson has toyed with in the past as well. Using hues to contrast between moments of ordinary prose and bouts of vivid descriptions gives an emotional punch-up to what would otherwise be undifferentiated scenes. Choices like these suggest that Anderson isn’t done experimenting with and evolving his personal style, even though there’s much here folks will recognize as his trademark techniques.

While it’s impossible to deny the level of craft bolstering every second of The French Dispatch, it’s not always in service of a deserving plot. The first of the three stories covered is good, but it ends in a moment of levity that I thought out of place tonally, given its subject matter of incarceration, manufactured art movements, and criminal insanity. And in the second, the journalist’s framing only confuses the narrative. The main problem with this tale of a youth rebellion against a neoliberal republic is not that the youths in question are portrayed negatively, but that they’re one note—holding protests and starting riots to attain some grand, vague notion of freedom. While I think Anderson captures the way we whippersnappers can needlessly police our peers, he ignores how organized movements respond to current political realities, and that the “touching narcissism of the young,” as he puts it, is more of a catalyst than a cause for it all.

I was all but ready to metaphorically put The French Dispatch down, until it arrived at its third and final story, “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner” by Roebuck Wright. Any issues I had with how the film was carrying on evaporated here. For one, the titular journalist actually feels like a participant in the events that follow, and while I was fine with Tilda Swinton or Frances McDormand being mostly offscreen narrators with minimal influence on the plot, Jeffery Wright’s character goes through a story of his own alongside his piece. As I watched him wander the bowels of a sprawling police bureau, trade quips with a pushy late-night host (Liev Schrieber), and muse over culinary writing, I realized Roebuck Wright is a unique character that Anderson, more than others, is poised to capture. Hilarious antics, a sense of loneliness, and a distinct feeling of joy tinged by melancholy all permeate the final minutes of The French Dispatch—there’s even a classic Anderson staple: the whimsical and slightly out-of-place third-act chase sequence. (Though there’s an aesthetic twist to it here that makes it feel fresh as ever.)

The poet W.H. Auden wrote that in order to critique art, one must first present their Eden. His was a coastal city, built with Victorian architecture, ruled by an elected-for-life monarchy, supported through farming, factories, and mining, with a complicated and obtuse system of weights and measures. Mine would probably be an American city in the 70s, also preferably on the coast and without institutional racism and queerphobia, that features an expanded public transit system, a ban on automobiles, and a plentiful number of parks that must allow dogs.

I can’t help but think of The French Dispatch as Wes Anderson’s Eden: the story of a magazine with an editor who gives his writers ample creative freedom and salary, nested in an ancient French city on the verge of modernity, and staffed by a group as diverse and interesting as the life on the streets and in the cafés and on the rooftops and upon the river. Even when the storytelling falters, you can always see the love for the story being told in the commitment that he and all the other members of the cast and crew bring to realizing this world. And while I can’t ignore the parts of The French Dispatch that left a bad taste in my mouth, I think that as time goes on I will only remember it more fondly.

Score: 3.5/5

How can I send a love letter via French Dispact?

I do not even know how I finished up here, but I believed this

put up was once great. I don’t know who you might be however certainly you

are going to a famous blogger for those who are not already.

Cheers!