Since Disney’s acquisition of Marvel, the blockbuster landscape has changed forever, causing studios like Sony, Fox, and Warner Bros to bend over backwards in an effort to replicate the same success. As a result, audiences have been receiving a perpetual loop of mediocrity. Every year bland super hero films flood cinemas nation wide, and while they garner success in box-office numbers, they have caused a tectonic shift in the way American blockbusters are produced. Original IPs are passed on for bankable properties. Uniqueness is stifled. And studio executives control final cuts. This type of production has been happening for so long that audiences have seemingly become conditioned to it, they want them, and often unwilling to give new properties a chance.

In this age, we rarely get a lick of originality in blockbusters, but in steps Steven Spielberg, the man who created the block buster, to show us how its done. After 2016’s The BFG, Spielberg, in all his tenacity, decided to helm Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One, a book whose mere concept alone would scare studio executives away. But Spielberg has cache, and only a man with his might can move mountains to make a film like this happen. From Jaws to Jurassic Park to E.T. to Indiana Jones, he is a goddamn master of the craft, and with Ready Player One, Spielberg seems to be metaphorically facing off against the super hero genre, violently shaking audiences into a realization that proclaims this is how a block buster should be made: with grandeur, with spectacle, and with imagination.

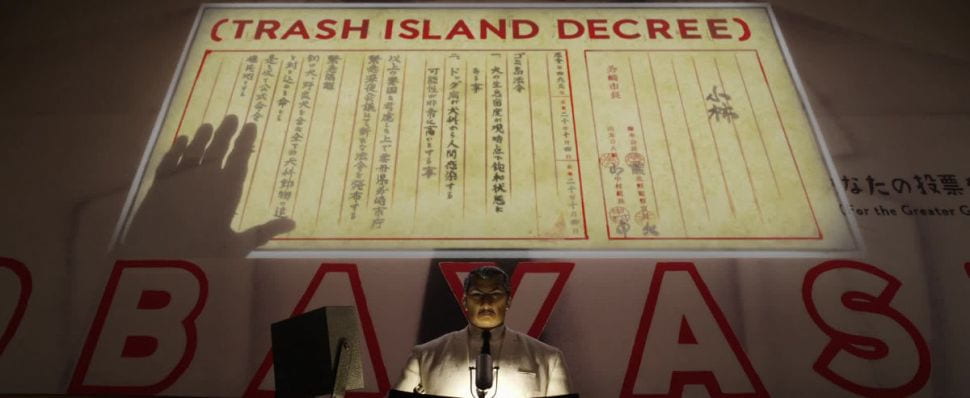

The film is set in 2045; society has become fixated with the Oasis, a digital realm where anyone can be anything. People go there to be the things they could never be in the real world, including the story’s main character Wade Watts (Tye Sheridan), an 18 year old orphan who lives in with his aunt in “The Stacks” of Columbus, Ohio. It’s been years since the death of the Oasis’ creator James Halliday (Mark Rylance) who posthumously issued a challenge for all users: find his Easter Egg via a series of trials and assume control of all his company shares and thus, control over the Oasis itself. The challenge has drawn the participation of millions of players including companies like IOI Corp. which uses an entire workforce in order to solve Halliday’s enigma and exploit the Oasis for monetary purposes. The extreme difficulty of the challenge has caused many to give up, but after Watts finds a clue, he is sent on a larger than life adventure to save the Oasis from forces that seek to ruin it.

The tremendous sense of adventure and child-like wonder is perhaps the film’s strongest asset. Spielberg is known for doing this and we see it particularly in E.T. and Raiders of the Lost Ark, and it is front and center with Ready Player One. The possibilities of the Oasis are only limited by your imagination, and the film does an effective job at conveying this endless potential due in large part to mixing and matching of pop culture elements in scenarios we have never seen before. The improbable nature of this film’s foundation and its ability to deliver something truly spectacular is almost always lost on modern blockbuster. The super hero genre (which is now the de facto blockbuster) has become nothing more than a recycling of the same tropes over and over again, and I can only take so much before the cinematic magic is gone, but Ready Player One recaptures the spectacle of the block buster and makes it fun again. Much like Watts going to the Oasis to escape his own reality, this film serves as a brief shinning moment of cinematic escapism before we are forced to go back to the same boring studio franchises we get every year.

All of this wonder would be meaningless if it weren’t delivered in a palatable form. Spielberg’s sensibilities are all over this film and they create a lean hero’s journey that has all of the adventure with none of the fat. There are action sequences that have vigor and thrills the likes of which few other director seems capable of delivering. Namely, a truly incredible race sequence that has Watts go through a morphing New York City while destruction and chaos engulf everything around him. Scenes are staged and blocked in cinematic ways that help deliver scale and movement. And his directing brings out well-rounded performances from everyone, particularly Olivia Cooke as Watt’s love interest Art3mus, Ben Mendelsohn as IOI’s CEO, and Rylance for what little we get of him. Every facet of this film exhibits a high level of craftsmanship and reenforces the idea that Spielberg is a true artist.

Special kudos need to be made to the team at Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) who did a lot of the heavy lifting for Spielberg. Most of the film takes place in the Oasis, and as such, thousands of VFX shots needed to be made from the ground up with only motion capture performances to help aide the process. Add in thousands of unique avatars and pop culture characters (each with their own specific details) and you have the perfect mix for a titanic project. What stands out is how ILM strikes the right ‘digital look’ for the film; the setting is a video game after all so it wouldn’t look right if it was photo realistic, but going too cartoonish would yield something repulsive. It’s somewhere in between and manages to walk the line perfectly. With so much digital work in the film, I wonder how much was at the hands of digital artists — especially since Spielberg ended up picking up and releasing The Post during the span of Ready Player One’s post-production— but I imagine there was some back and forth with regards to creation and direction. Nonetheless their work on the film is nothing short of astounding.

And of course there are problems with the film, but I believe them to mostly be non-factors. The beginning plays out like a user manual as Watts describes the setting, players, and rules of the world. The social commentary on living online rather than the real world is only partially covered. And it’s reasonable to say the plot is conventional, but all of these elements are rather important to the assembly of the film. What I see is a film that is so focused on creating a heroic adventure that it sees no need to bog itself down with sub-themes and periphery material. The film wants to be a concentrated cinematic experience more than anything else and it’s focus on that goal is what makes it so enthralling.

All of these components create one of the most unique block busters I have seen in years. The film is essentially what Luc Besson tried to do with last year’s Valerian and the City of A Thousand Planets— that is to create a non-franchise blockbuster on a massive budget in a well realized world —, but where that film failed, this film succeeds. It is a block buster in its truest form, and Ready Player One not only allows for an escape from the troubles of our own world, but an escape from the banal blockbusters that litter the cinematic landscape.

Score: 4.5/5