Events of the 1930s:

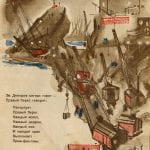

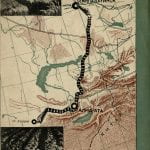

At the onset of this decade the Soviet Union was in the middle of the First Five-Year Plan. In order to further facilitate collectivization, the Politburo, in early 1930, initialized dekulakization, a process through which the kulaks (wealthy peasants) were to be liquidated as a class with their land and wealth being assigned to the kolkhoze (collective farm). By the end of the First Five-Year Plan in 1932, the industrialization campaign could be considered a rousing success (Freeze, 2009, pp. 346), however collectivization was still largely a work in progress (Freeze, 2009, pp. 351). During this same period the population of major cities exploded, as peasants moved in large numbers from the village to the city. In 1933 the Soviet Union was faced with a famine related to grain production that has been estimated to have killed millions. Despite this famine, the Second Five-Year Plan, also initiated in 1933, largely ignored agriculture. Instead, it focused on further industrialization, with a primary concentration on the workers technological efficiency (Freeze, 2009, pp. 358). In accordance, the Stakhanovite movement began in 1935 as a means of celebrating exceptional workers who had greatly surpassed their production quotas and had mastered the utilization of technology. From 1936-1938 the Great Purge wreaked havoc throughout Soviet society as individuals, primarily social, political, and economic elites, were charged in show trials with the crime of being wreckers with sentences ranging from the gulag to death. Towards the end of the decade the USSR began preparing for the upcoming war, signified through the signing of the Non-Agression Pact with Germany in 1939 which enabled both countries to greatly expand their borders.

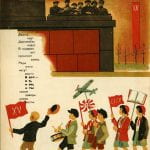

Art of the 1930s:

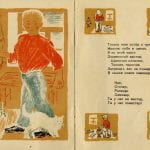

In the 1930s the Soviet government began to exert more control over the artistic process which created further homogeneity in the cultural sphere (Clark et al., 2007, pp. 136). 1932 saw the government pass a resolution banning independent writers organizations, including the powerful Russian Association of Proletarian Writers (RAPP), instead creating a state controlled Union of Writers (Clark et al., 2007, pp. 139). In 1934 at the First Congress of the Writers Union Maksim Gorky, a major Soviet writer, and Andrei Zhadanov, one of the most powerful leaders in the Communist party, announced socialist realism as the ideal future for Soviet art (Senelick & Ostrovsky, 2014, pp. 350). Socialist realism was pitched as providing a truthful representation of the world that would energize the masses towards the building of the Soviet state (Davies & Harris, 2014, pp. 249-250). Art in general was further centralized in both 1935 when the Committee of Arts Affairs was formed to oversee the creation of all forms of art in the Soviet Union (Clark et al., 2007, pp. 145), and in 1938 as that committee was put under control of the Central Committee Directorate for Propaganda and Agitation (pp. 148). In turn, censorship thrived during this era as the Soviet government dictated what cultural content would be shared with the public (Senelick & Ostrovsky, 2014, pp. 350). As the state gained more control over art, the official state newspaper, Pravda, began publishing “anti-Formalist” articles that denounced modernism and propagated the idea that Soviet culture must be “simple” and consumable for the general public (Clark et al., 2007, pp. 229).