Basic Information

Frederick Douglass was born in Cordova, Maryland on February 14th, 1818, as a slave. Douglass was known for his position in the women’s rights movement and his work with Abraham Lincoln in the abolition movement.

Background Information

Douglass was born into slavery, and was a slave until he escaped in 1838 to New York, a free state. Douglass was known as an abolitionist, and worked closely with Elizabeth Stanton in the Seneca Falls Convention. He was also known for helping Lincoln to ensure that emancipation was an outcome of the Civil War.

Douglass didn’t know much about his mother, since she lived on another plantation and died when he was seven and his father was an unknown white man (Editors, 2009). He taught himself to read and write when he was young, occasionally being taught by his owner’s wife. The first book Douglass possessed was The Columbia Orator, this had revolutionary speeches, debates, and writings on natural rights which taught him that there was a connection between literacy and freedom (NPS). At age 20, Douglass met his first wife, Anna, who helped him escape from slavery. Once he escaped from slavery, he married Anna and began a family (Trent, Frederick Douglass).

Contributions to the First Wave

Once in New Bedford, Douglass began to go to abolitionist meetings, eventually meeting William Lloyd Garrison. With his help, Douglass became a big voice in the abolition movement. He worked with Garrison on his newspaper, and then began his own newspapers, writing about slavery and abolition. He also traveled around the country speaking about abolition. Douglass worked closely with the Lincoln administration to have emancipation be the agreement to end the Civil War. He also encouraged African Americans to fight in the war and helped recruit troops for the war. With that encouragement, African Americans were able to fight for their freedom, and Lincoln was able to support emancipation to free the slaves after the war. He also advocated for Constitutional amendments that would permanently change the status of African Americans in the United States (Trent, Frederick Douglass). Douglass advocated for the 14thand 15thamendments, which allowed African American men the ability to vote and citizenship.

Douglass also worked with Elizabeth Stanton and Susan B. Anthony for woman suffrage. He founded the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), which asked for universal suffrage, which at its beginning was rights for all. As time went on, universal suffrage became the right for educated white women to be able to vote, leaving African American women out of the equation. Douglass did not agree with this idea, and there soon became separation and disagreement within the association. This ultimately led to the disbandment of the group.

At the Seneca Falls meeting in 1848, Douglass was one of the only men that signed the Declaration of Sentiments. The Declaration stated the rights that women should have, which were the same as men. The purpose of the Seneca Falls Convention was to determine how to achieve political, social, civil, and religious rights for women. Douglass was the only African American that was present at the meeting. African American women often got left out of the conversation quite a few times as the talks of suffrage increased and spread. This showed the hardships that African Americans went through to be able to get their rights, along with the division and dissolve of the AERA.

“Thus is slavery the enemy of both the slave and the slaveholder”

~ Frederick Douglass (Editors, 2009)

Analysis and Conclusion

Douglass faced many hardships throughout his life, not only growing up, but working with Stanton and Anthony as well. As stated previously, Douglass was born into slavery, not knowing who his mother or father was. He was moved from home to home, consistently being whipped and beaten for trying to learn. He lived through the harshness of slavery and long nights of work. Douglass was eventually moved back to a previous owner because he refused to be disciplined. When he was moved back to his previous owner, he decided that he was going to escape to New Bedford with Anna.

Later in life, Douglass had a hard time having his voice heard and accepted by Stanton and Anthony. When the 15thamendment was passed, allowing black men to vote, completely ignoring the other sex, the AERA met and Stanton picked a political party to gain support from: The Democrats. Douglass stated that “the Democratic Party is on record as opposing any move to give suffrage or civil rights to blacks” (Moore, 1995). Stanton decided to ignore Douglass and still fight for the Democratic support. This led to harsh reality that Stanton and Anthony were fighting for educated white women’s rights first, and then were going to fight for the rest of the women. Douglass continued to fight for African American rights up until he passed away in 1895.

References

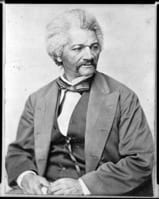

Frederick Douglass (c. 1870) Jesse Bravo and the Chris Webber Collection of Artifacts and Documents, Retrieved May 22, 2019, from https://www.whitehousehistory.org/frederick-douglass Chri

Editors, (2009, October 27). Frederick Douglass. History.com Retrieved May 1, 2019, from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/frederick-douglass#section_3

Frederick Douglass. (n.d.). National Women’s History Museum. Retrieved May 1, 2019, from http://www.crusadeforthevote.org/douglass

Frederick Douglass (n.d) National Park Service Retrieved May 1, 2019, from https://www.nps.gov/frdo/learn/historyculture/frederickdouglass.htm

Frederick Douglass (n.d.) (Women’s Rights) National Park Service. Retrieved May 1, 2019, from https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/frederick-douglass.htm

Trent, N. (n.d.). Frederick Douglass: Abolitionist, Journalist, Reformer, 1818 – 1895. National Civil Rights Museum. Retrieved May 1, 2019, from https://www.civilrightsmuseum.org/news/posts/frederick-douglass-abolitionist-journalist-reformer-1818-1895

Wheeler, M. S. (1995). One Woman One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement. Troutdale, Or.: NewSage Press.