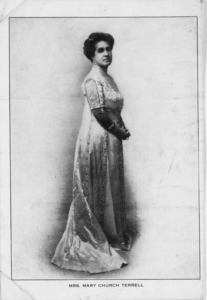

Basic Information

Mary Church Terrell was born on September 23, 1863 in Memphis, Tennessee. Terrell was an African American educator and activist who would become the first president of the National Association of Colored Women or NACW. Terrell advocated throughout her career for suffrage as a woman’s right as a citizen as well as equal rights treatment for black women.

Background Information

Terrell’s family consisted of her father Robert R. Church, mother Louise Ayers Church, and sisters Annette and Sarah Church. Terrell’s parents, previously slaves, became owners of a small business after they had gained freedom (Association for the Study of African American Life and History [ASALH], 1954). Terrell’s family was from Memphis, Tennessee but throughout her career Terrell would move from place to place, until finally settling in Washington D.C. Since she was a little girl, Terrell had shown interest and believed in women’s suffrage and rights and wanted to advocate for her passionate beliefs (Council, 2018). She entered Oberlin Academy where she would eventually graduate as one of the highest in her class and gain experience in the abolitionist community for nine years (ASALH, 1954). After graduating Terrell proceeded to find work at Wilberforce University, M Street High School, and Howard university. Terrell learned multiple languages including French, German, Italian, Greek and Latin and at her death was one of the most distinguished women of color in America (ASALH, 1954). Terrell’s views on race rejected the notion of African Americans being second class citizens and rather presented that black men and women are fully gauged members in different aspects of American society, with obligations and purpose (Council, 2018). However, Terrell experienced and believed for herself that black women were “double-crossed” by the interlacing of both racism and sexism. Terrell aimed to show that despite these drawbacks’ black women in particular, were nothing like the stereotypes that attempted to depict them (Council, 2018). This ultimately fueled Terrell and her ambition to make a difference for women of color through her works on feminism and suffrage.

Contributions to the First Wave

Mary Church Terrell throughout her career, contributed much of her efforts towards feminism and the suffrage movement. Because Terrell was an African American woman, most of her efforts were geared towards the issues of black feminism and suffrage for women of color. One of the major contributions to first wave feminism that Mary Church Terrell was able to make was becoming the first president of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) (Ramdani, 2015). Terrell explained that the importance of an organization such as NACW was to bring individuals together and fight for a common cause (Ramdani, 2015). The NACW worked to address social issues that had struck African American communities, such as disproving the pseudoscientific ideas that placed blacks as second-class citizens. (Williams, 1998). Terrell worked with members of the NACW and published National Notes, the newsletter for the NACW, established settlement houses, as well as working girl’s homes. Terrell’s work within the National Notes were particularly powerful, as she was a very educated woman, Terrell used her literacy to her advantage to spread positive information about equal treatment of black women as well as opportunities for women of color to find work and/or education (Williams, 1998). In addition to Terrell’s writing, she was also a very powerful speaker, and would go on multiple speaking tours throughout her career in both the United States and Europe. Terrell used her experience as a black woman in America to explain how her other black women were treated, in hopes to globally gain support for the equal treatment of black women (Ramdani, 2015). Terrell’s speeches, however, were not only targeted towards the black feminism movement, but also contributed to the promotion of women’s suffrage (Williams, 1998). Mary Church Terrell was an active spokesperson for the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and would often speak at annual NAWSA meetings (Ramdani, 2015). Terrell even went as far as to picket outside the white house with members of the Women’s Suffrage Party (WSP) in order to bring attention onto the seriousness of the women within the movement (Gilliam, 1998). Most of Terrell’s work for women’s suffrage was done through some written literature but consisted mainly of public speaking events (Evans, 1987). Terrell was quite vocal on issues she was passionate about and being a powerful speaker with plenty of knowledge, her speeches became the gateway for her to express her beliefs and ideas. However, it is important to note that much of Terrell’s early work on suffrage confirmed the white vote. As Terrell began advocating for the women’s suffrage movement, she saw herself as an “ambassador” for white women’s suffrage rather than for women of color (Nelson, 1979). This view that Terrell held of herself within the suffrage movement was conflicting as she believed that all women deserved to vote not just those who were white (Council, 2018). Terrell first became aware of this idea when her peer and group mate from NAWSA, Fannie Barrier Williams discussed that when the advancement of black women from slavery was brought up, it was almost always through a white gaze, explaining that women regardless of race attempt to be accepted into an established white-constructed class and gender system (Council, 2018). Black women were only seen as respectable if they behaved in ways that matched the white ideal of femininity and belonged to upper class. Much of Terrell’s early work was used to establish the white women’s vote by urging that black women should adopt these traits and work up to be successful (Council, 2018). However, as Terrell realized how this may skew what she is trying to promote, she was able to use this idea to argue that white women are not the only ones that can possess these desirable traits. Terrell argued that rather than black women and women of other races possessing white ideal characteristics, that these become characteristics of all respectable women regardless of their race or class (Council, 2018). It was then that Terrell was able to move forward with her speaking tours and literature work to address the racial gap created by the dominants within American society.

“My sisters of the dominant race, stand up not only for the oppressed sex, but also for the oppressed race!”

~ Mary Church Terrell (Wheeler, 1995, p. 145)

Analysis and Conclusion

Looking at the contributions that Mary Church Terrell made to women’s suffrage and black women’s rights, she certainly emerges as a dynamic character. One of Terrell’s major strengths as an educated woman with high credibility and experience, was that she was able to move many people with her speeches and literature works, in both America and abroad. With her amount of knowledge and involvement in different organizations Terrell was able to bring awareness to multiple issues and effectively counter arguments that were thrown her way. One major argument, as discussed previously, that Terrell fought to counter was that of the pseudoscientific belief that blacks were second class citizens. Terrell, through her discussion of black women and their possession of the same traits as white women was able to address that many women of color can and should be just as valued as white women. The time period in which Terrell was advocating was a time when racial segregation was beginning to peak, thus it is not surprising that much of her work focused on black women and their rights. With this being said, one of the struggles that Terrell faced at the beginning of her suffrage career was that though she was fighting for black women’s rights and suffrage she saw herself as a helper of the white suffrage movement (Council, 2018). This drew away from her ability to focus her early efforts on black women’s suffrage as well. However, Terrell was a powerful leader and her career progressed and eventually she was able to effectively gauge her passion for black women’s rights. Mary Church Terrell involved herself in many different aspects of the feminism and suffrage movement, and ultimately left a large impact during the time period, that is still relevant today.

References

Association for the Study of African American Life and History. (1954). Mary Church Terrell. The Journal of Negro History, 39(4), 334-337. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/stable/2715413

Council, A. R. (2018). The personal is political: Mary Church Terrell, intellectual activism, and black feminist thought. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/2081762748?accountid=14784

Evans, E. A. (1987). Activity of black women in the woman suffrage movement, 1900-1920. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/303526399?accountid=14784

Gilliam, A. (1998). Black suffragettes — from 1848 to 1920. Washington Informer. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/367762927?accountid=14784

Nelson, M. (1979). Women suffrage and race. Off our Backs, 9, 6. Retrieved fromhttps://search.proquest.com/docview/197141368?accountid=14784

Ramdani, F. (2015). Afro-American women activists as true negotiators in the international arena (1893-1945). European Journal of American Studies, 10. Retrieved from https://www.eaas.eu

Terrell, M. C. (1905) Mary Church Terrell Papers: Miscellany, -1954; Printed matter; Lecture notices, 1905 to 1938, undated. – 1938. [Manuscript/Mixed Material] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mss425490695/.

Wheeler, M. S., (1995). One woman one vote: Rediscovering the woman suffrage movement. Troutdale, Or: NewSage Press.

Williams, L. S. (1998). National association of colored women. In W. Mankiller, G. Mink, M. Navarro, B. Smith, & G. Steinem (Eds.), The Reader’s Companion to U.S. Women’s History. Retrieved from http://link.galegroup.com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/apps/doc/A176833577/AONE?=.wash_main&sid=AONE&xid=e8cd958c