Basic Information

Victoria Claflin Woodhull was born on September 23, 1838 within the rural town of Homer, Ohio. She was a polarizing figure, and her brief time on the front lines of the women’s suffrage movement was full of both triumph and intrigue. With the funds raised by her and her sister as the first female stockbrokers on Wall Street, Woodhull also created her legacy as the first woman to campaign for presidency of the United States. Woodhull’s remarkable drive allowed her to rise beyond many of her peers and defy all expectations imposed upon the women of her time.

Background Information

Despite the tall tales that Woodhull and Tennessee—known as “Tennie”—spun for the press during their ascent on Wall Street, primarily that they were the daughters of an esteemed lawyer and thoroughly educated, the two sisters were raised in squalor (MacPherson, 2015). Their father, Reuben Buck Claflin, was a man of little means and fewer morals. He held no job but that of a conman and criminal, and his antics led Woodhull and Tennie into a fraudulent life of fortune-telling and faith healing (MacPherson, 2015). Rumors would have it that his eldest daughters, Mary and Margaret, and possibly even Tennie, were pulled into prostitution on his behalf (Underhill, 1996). Their mother was no better, a religious and mentally compromised zealot who alternated between abuse and protection of her children (MacPherson, 2015). They pressured their daughters to be breadwinners for the family, and Woodhull especially began to rely on her supposed clairvoyance and ability to commune with spirits throughout her exploits. Later on, her travels to New York in 1868 were inspired by her conversations with Demosthenes, an ancient Greek orator who often guided her actions (Gabriel, 1998).

Woodhull was poorly educated, having only received an inconsistent stretch of schooling from the ages of eight to eleven (MacPherson, 2015). When the Claflin family traveled to Mount Gilead, Ohio in 1853, Woodhull’s views on love and marriage shifted forever. At fifteen she was forced into a marital union with Canning Woodhull, a man of twenty-eight years who proved to be an abusive and adulterous alcoholic (MacPherson, 2015). It was during the course of this marriage that she gave birth to her only son, Byron, who suffered from severe mental disabilities and spoke only in grunts (Goldsmith, 1998). It has been said that her son was what motivated her to advocate for the eugenics movement later in life, as she blamed his condition on her first husband’s alcoholism and proclaimed that unloving and unfit marriages will result in damaged children (MacPherson, 2015). Her miserable marriage and experiences with other women in similar situations led her to become a staunch supporter of “free love” up until her later years. According to Woodhull, free love was “first love of each by each of the parties; second, a desire for the commerce on the part of each, arising from the previous love; and third, mutual and reciprocal benefit.” (MacPherson, 2015, pg. 92)

She had her second child, a healthy daughter by the name of Zulu Maude, in New York on 1861. It was in New York that she met her second husband, Colonel James Harvey Blood, a Civil War hero and impassioned Spiritualist who introduced her to radical and progressive movements of reform (Gabriel, 1998). After a short stay in Cincinnati and having been chased out of their home due to accusations of brothel activity, Woodhull and Tennie made their way to No. 17 Great Jones Street in New York, led by Woodhull’s spiritual vision (Gabriel, 1998).

Contributions to the First Wave

Woodhull’s ambitious nature, beauty and extensive training with con artists enabled both her and Tennie to charm the prestigious Cornelius Vanderbilt (MacPherson, 2015). Bankrolled by Vanderbilt and showered with tips on how to navigate their new financial sphere, the two sisters garnered enough wealth to open their own firm, Woodhull, Claflin & Company (Underhill, 1996). It was during this time that Woodhull caught the eye of Susan B. Anthony, and it was not long before they hit it off. Anthony admired Woodhull’s enterprise and courage in the face of a male-dominated field and stated that the sisters were stimulating “the whole future of woman.” (MacPherson, 2015, pg. 49)

Spurred onward by her success and with a fierce motivation to ease the plight of women, Woodhull put her name up for nomination for the presidency on April 2, 1870. In order to spread the word of her nomination and lend her voice to the women’s movement, Woodhull and Tennie utilized the help of Stephen Pearl Andrews, a genius linguist and fellow proponent of free love, to publish their own newspaper: Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly (Underhill, 1996). As the sisters were uneducated, Andrews—alongside Colonel Blood—became responsible for penning the majority of their articles (MacPherson, 2015). Their paper became a means of fighting back against opponents and pushing their beliefs on the issue of marriage. Woodhull was opposed to the institution of marriage for most of her life, and she launched a tireless crusade to advocate for the rights of women to divorce and choose love however and whenever it pleased them (MacPherson, 2015). She scorned both the idleness of women, especially the rich, and the double standard in which men and men alone were allowed to engage in debauchery and sexual ventures while prostitutes were vilified (Goldsmith, 1998). Because of this, the sisters were frequently under fire with accusations of prostitution and untoward behavior. Nonetheless, they argued for fair treatment of prostitutes and free love in a monogamous society (MacPherson, 2015).

During her time amongst the suffragists, Woodhull attended conventions and gave speeches that revitalized the movement. It was also Woodhull—through the aid of Benjamin Butler, a powerful congressman—who introduced to the suffragists the idea of fighting for women’s suffrage on account of a loophole in the Constitution, specifically the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments (Gabriel, 1998). In doing so, she became the first woman to address a congressional committee (Gabriel, 1998). She argued that the language, in emphasizing “citizens” and not “men,” did not exclude women from their rights (MacPherson, 2015). While Congress put it off as an issue for the states to decide, it was still an incredible moment of pride for Woodhull and the other suffragists (MacPherson, 2015).

By 1872, Woodhull had officially been nominated for the presidency by the Equal Rights Party, alongside Frederick Douglass—a former slave, abolitionist and women’s rights advocate—as the vice-presidential nominee (Gabriel, 1998). Frederick Douglass was not in attendance of the convention, however, and he never responded to the nomination (Gabriel, 1998). According to the Constitution, Woodhull was not eligible for the presidency as she was not yet 35 (MacPherson, 2015), but her campaign was monumental in bringing attention to women’s issues and challenging the status quo. She tried again for a nomination in 1884 and 1892, though nothing came of it (MacPherson, 2015).

Woodhull and Tennie were condemned to a later life of scandal and damage control, most notably when they exposed Henry Ward Beecher, an esteemed reverend in New York, for his affair with the wife of newspaper editor Theodore Tilton (MacPherson, 2015). During the conflict, Woodhull, Tennie, and Colonel Blood were arrested for passing obscene material through the mail (MacPherson, 2015). This would not be the first time Woodhull was jailed, and Susan B. Anthony and the other suffragists could not withstand the constant public backlash. Where they had been her strongest defenders, as Woodhull became more radical and was pulled repeatedly into scandalous conflicts with the men they despised, the women began to feel that she had compromised the integrity of the movement (MacPherson, 2015). A deep rift formed between them, and Woodhull was eventually forced to separate from the suffragists (MacPherson, 2015).

“I am a free lover. I have an inalienable, constitutional and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please.”

~ Victoria C. Woodhull (Gabriel, 1998, pg. 148)

Analysis and Conclusion

Although Woodhull became more conservative as she aged, even later denouncing free love in an attempt to regain her respectability in a world that fought her at every turn, she nonetheless represented notions that were quite ahead of her time. For all her radical and progressive ideas, however, it is impossible to deny her role as a product of her problematic environment. Although her support for eugenics at that time—specifically stirpiculture, which originated in the Oneida Community and was a form of “positive eugenics” (Goldsmith, 1998)—was not rooted in the same level of extremities (that is, eliminating those that are deemed “inferior beings”) practiced later on by the Third Reich and other movements, it was still a springboard for cultivating racist and classist mentalities. It is a slippery slope, and Woodhull was certainly not immune to prejudices. Though she was not quite so overt as the likes of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Woodhull internalized racist tendencies as well. In her defense of free love, she once alluded that black men would be undesirable to white women (Woodhull and Carpenter, 2010). In one of her speeches, “Tried as by Fire,” she also called for women to embrace their white-robed purity (Woodhull and Carpenter, 2010). It is important to take into account her flaws alongside her contributions, as these warped views may have influenced how she interacted with her world and left her with limitations she may not have been able to overcome.

She became far more unstable as time went on, likely the result of the pressures she endured in her time in the spotlight. Woodhull was ripped apart by her opponents and even those she once called allies, and it certainly took its toll on her. While she was strong in the public eye and maintained a composure that many could not boast, her health and mental resilience deteriorated (MacPherson, 2015). Her abuse as a child and within her first marriage seemed to have been massive contributors to both her ideologies and her downward spiral, but it is impossible to tell how these beliefs may have manifested otherwise.

Tennie also played an invaluable role in Woodhull’s success, as it is unlikely that she would have gotten so far without the support of her sister. Her sister was an intense advocate for women in her own right, and it was her charisma and fiery spirit that enabled Woodhull to become closely involved with so many important figures. They played off one another’s strengths and made up for each other’s weaknesses. In the end, Tennie was the one Woodhull leaned on when the weight of the world came to be too much to bear, even substituting for her as a public speaker when Woodhull was too exhausted (MacPherson, 2015).

Victoria C. Woodhull was an undeniable powerhouse in first-wave feminism, responsible for paving several pathways for women in the United States. She helped show the country that there is not only one way to love and be loved, and that women are capable of balancing both beauty and intelligence in their rise to the top. Although she passed away at the age of 88 on June 9, 1927, she left behind a legacy that will never be forgotten and encompassed both the admirable and extremely questionable sides of white feminism in the 20th century.

References

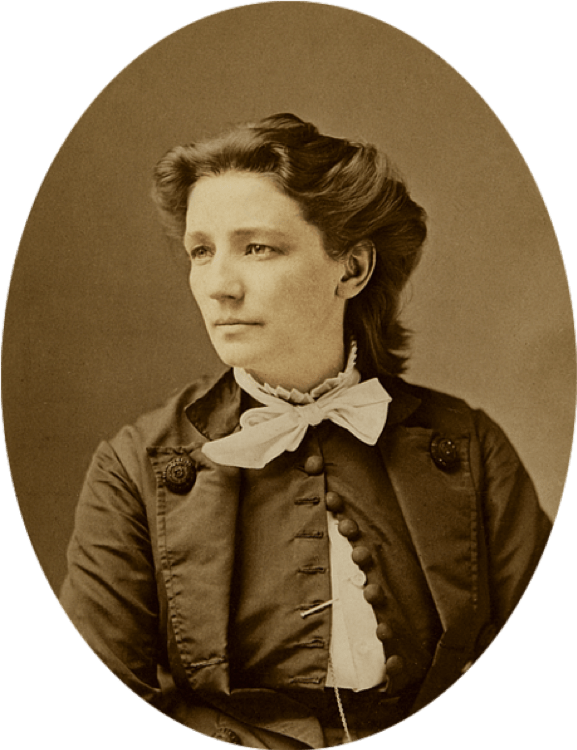

Brady, M. (1866-1873). Portrait Photograph of Victoria Claflin Woodhull. Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum, Historical Photographs and Special Visual Collections Department, Fine Arts Library. Retrieved May 17, 2019 from Wikimedia Commons. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Victoria_Woodhull_by_Mathew_Brady_c1870.png#filelinks)

Gabriel, M. (1998). Notorious Victoria: The Life of Victoria Woodhull, uncensored. Chapel Hill, N.C: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

Goldsmith, B. (1998). Other Powers. Harper Perennial.

MacPherson, M. (2015). The Scarlet Sisters: Sex, Suffrage, and Scandal in the Gilded Age. New York: Twelve.

Underhill, L. B. (1996). The Woman Who Ran for President: The Many Lives of Victoria Woodhull. New York: Penguin Books.

Woodhull, V. C., & Carpenter, C. M. (2010). Selected Writings of Victoria Woodhull: Suffrage, Free Love, and Eugenics. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.