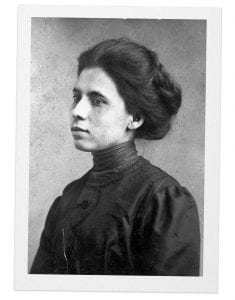

Basic Information

Jovita Idar was a teacher, journalist, civil rights activist, nurse, and suffragist. Idar boldly spoke out about the injustices facing Tejanos during the early 1900s. Jovita Idar was born on September 7, 1885 in the borderland of Laredo, Texas. Idar was the second of eight children born to Jovita and Nicasio Idar. Idar attended the Holding Institute in Laredo, Texas where she earned her teaching certificate in 1903 (Jones, 1995).

Background Information

Once an educator, Idar was exposed to the harsh realities that her students were experiencing both in and outside of school. She noticed a lack of supplies and resources and the supplies the students did have were in poor condition. Frustrated with the subpar conditions in the schools, Idar quit teaching to become a journalist. Idar’s goal was to highlight the inequalities that Mexican Americns were facing in the state of Texas. Nicasio, Jovita’s father, had egalitarian beliefs and he openly discussed and opposed race relations in the south. He wrote as a journalist and owned a local newspaper called La Crónica. Idar began writing for La Crónica under the pseudonyms Ave Negra, which means black bird and Astrea, which is a reference to the Greek goddess of justice (Life story: Jovita Idar Juárez, 2021). This is significant to note because it would foreshadow the life that Idar would go on to live. These pseudonyms highlight Idar’s beliefs and her dedication to fight for equity and women’s rights. Idar used the privilege that she had as an educated Mexican American woman during the 1900s to advocate for the rights of other women and children. This was a very daunting task, especially when considering the brutality and racism that Mexican Americans were experiencing during this time.

The Mexican-American War caused the United States to acquire Texas, previously the sovereign state of Mexico, as a territory. Tejanos also known as Mexican Americans faced brutal violence from local mobs and were routinely discriminated against by white Americans on land that was native to them. Mexican Americans faced displacement, the criminalization of their native language, lynching, extreme poverty, and unequal access to resources. These travesties caused Idar to speak out for her community and people. Idar did not let her position in American society silence her voice in any way.

Contributions to the First Wave

Idar joined her family’s newspaper with a goal of speaking out against the racism, violence, poverty, and inequality that Mexican Americans faced. Idar also used her platform to speak in favor of women’s suffrage and to shed light on the women’s rights movement. During the early 20th century, racial tensions between Tejanos and Anglo Americans were volatile. Idar used her notoriety to address the issues affecting the Mexican community despite the possible risk to her and her family. In addition to publicly advocating for effective change, Idar and her family also organized the first political convention for Latinx people in the United States. On September 22, 1911, the Idars held the First Mexican Congress. This Congress allowed Mexican Americans across the border to collectively discuss civil rights, protecting their culture, and education (Turner et al., 2015). The First Mexican Congress was nine days long and was the catalyst for the creation of two other organizations. Both the Great Mexican League for Beneficence and Protection and the League of Mexican Women were created as a result. Idar was the first president of the League of Mexican Women and the organization was created to provide free education, food, and clothing for women and children. The League of Mexican Women emphasized the importance of educating women and fought against the segregation of school aged children (Masarik, 2019).

Jovita Idar was involved in numerous civil rights organizations and movements. She continued to work for the League of Mexican Women, but in 1913 Idar crossed the Mexican-American border to care for the injured during the Mexican Revolution. Idar selflessly acted as a nurse and cared for countless individuals when there was very limited medical aid. Idar constantly risked her own life to help others because women from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds participated in the revolution and Idar did her part to support those women. She worked as a nurse for an organization called La Cruz Blanca, a group similar to that of the Red Cross which was composed of mostly women. Idar returned to Texas later in 1913 to continue her journalism (Alexander, 2020). Following her return to Texas, Idar began writing for a newspaper called El Progreso. There she wrote a piece opposing President Wilson’s orders to send troops to the Mexican border. It was virtually unheard of for a Mexican woman to publicly challenge the president of the United States, but Idar did so fearlessly. After the publication of such a bold article, the U.S. army and the Texas Rangers sent officers to shut down El Progreso. Idar stood in front of the building and refused to let the Rangers enter. This was dangerous for Idar, but she was dedicated to advocating for the rights of Mexican Americans and their First Amendment right. The Texas Rangers eventually returned and were able to shut down El Progreso, but Idar returned to La Crónica to continue speaking out against the inequalities Mexican Americans were facing (Alexander, 2020).

In 1917, Idar married Bartolo Juárez and they eventually relocated to San Antonio, Texas where Idar continued to support and engage with the women in her community. Idar was driven to create better living conditions for the women and children in her Texas. She opened a free kindergarten that ensured a quality education for young Mexican children. Idar continuously denounced the poor education quality for Mexican children and she related the subpar education to the disadvantaged socioeconomic standing of Mexican Americans in Texas during this time. Jovita also advocated that Tejana women should be able to earn a quality education because it would allow for them to be better equipped to support their families. Idar argued that educating women would empower the entire Mexican community because women are responsible for numerous roles within the community (Turner et al., 2015). Idar continued working with women and children and advocating for quality education until her passing in 1946.

Educate a woman and you educate a family.

~Jovita Idar (Alexander, 2020)

Analysis and Conclusion

Jovita Idar was a hidden figure within U.S. history, especially in the state of Texas. Idar was a pioneer for the Latinx civil rights movement and she contributed significantly to the progression of Mexican Americans in Texas and the United States. Jovita Idar fought for the civil rights of women and others who were also marginalized. Idar used the privileges that she did have to advocate for the Mexican community. She was iconic because she dared to speak out about the issues that plagued the Mexican-American community during a time when many people were fearful. Idar challenged the structures that enforced the domination of certain individuals based on race, gender, and class. Idar advocated for and was deeply engaged with her community and she continued to work for equity until her final days. The problems that Idar advocated for during the early 1900s are still relevant today. For example, quality education and women’s rights are still challenges that marginalized women experience to this day and Idar was advocating for changes back then. We see that Idar was dedicated to the improvement and advancement of women and children and this is made evident by the work that she did.

References

Alexander, K. L. (2020). Jovita Idár. National Women’s History Museum. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/jovita-idar#_ftn1

Baker Jones, N. (1995, February 1). Idár, Jovita (1885–1946). TSHA. Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/idar-jovita

(Image) General Photograph Collection. UTSA Libraries Special Collections. (1905). Retrieved February 3, 2022.https://web.lib.utsa.edu/special-collections/photographs/gallery/view/14117

Life story: Jovita Idar Juárez. Women & the American Story. (2021, June 23). Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://wams.nyhistory.org/modernizing-america/xenophobia-and-racism/jovita-idar-juarez/

Masarik, E. G. (2019). Por la Raza, Para la Raza: Jovita Idar and Progressive-Era Mexicana Maternalism along the Texas–Mexico Border. Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 122(3), 278–299. https://doi-org.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/10.1353/swh.2019.0019

Turner, E. H., Cole, S., & Sharpless, R. (2015). Jovita Idar. In Texas women: Their histories, their lives (pp. 225–243). Essay, University of Georgia Press.