Basic Information

Emilia Casanova de Villaverde was a prominent political activist from Cuba, best known for her work with the movement for Cuban independence. She formed one of the earliest all-women organizations committed to the Antillean emancipation struggle, La Liga de las Hijas de Cuba. Casanova de Villaverde was the first Cuban woman to compose political writings, address the United States Congress as the representative of Cuban women fighting for independence, and make an effort to internationalize Cuba Libre (Ruiz & Sánchez-Korrol, 2006).

Background Information

Casanova de Villaverde was born in Cárdenas, Cuba in 1832. She was raised in a very conservative home and her parents were wealthy slave holders. Spanish colonial rule over Cuba benefited Casanova de Villaverde ‘s Spanish family, who lived there. Casanova de Villaverde , though, supported the Cuban revolutionaries’ desire for Cubans to run their own nation. Although she was a part of the Creole elites, from a young age Casanova de Villaverde agreed with the Cuban revolutionaries who believed Cubans should rule their own country and she wanted to distance herself from her father’s opposing conservative views. She advocated for Cuba’s independence and was not shy about expressing her own views. It is said that during a banquet a very young Casanova de Villaverde bravely gave a toast in the presence of the Spanish authorities and said, “to the freedom of the world and to the independence of Cuba,” (Ruiz & Sánchez-Korrol, 2006).

What confirmed her beliefs in an independent Cuba was her first trip to the United States with her father and brothers. During this trip she was allowed the chance to meet Cuban exiles who believed in Cuban independence and had left the island due to fear of being punished by the Spanish who were occupying Cuba (Boomer, 2022). This is when her involvement in the revolution began. Casanova de Villaverde wanted to stay in New York to continue learning from the Cuban exile community but was persuaded to go back to Cuba after only three months. Before she left she offered her help to the Cuban revolutionaries and they sent documents that promoted revolution with her to smuggle into Cuba. She distributed the documents with the help of her brothers in the hope to inspire more Cubans to lend support to the independence movement. Due to Casanova de Villaverde ’s continued outspoken disagreement with Spanish rulers in Cuba and her family’s fear of being punished they fled to Philadelphia in 1854 when she was 19 years old (Boomer, 2022). Soon after Casanova de Villaverde met and married Cirilo Villaverde, a Cuban exile and writer who dedicated his life and work to freeing Cuba from Spanish control (Encyclopedia of Latin American history, 2022). After her marriage she moved to New York with her husband and reconnected with the Cuban exile community she had met years ago and became an active member of the community.

Contributions to the First Wave

One of Emilia Casanova de Villaverde best known contributions was founding the first political club of women, the Liga de las Hijas de Cuba (the League of Daughters of Cuba). With tensions growing in Cuba in 1866, the Spanish government increased taxes and made it illegal for Cuban reformers to meet in order to suppress the independence movement. However, this led to the Ten Years’ War for Cuban independence in 1868. When the Ten Years’ War started in 1868, Casanova de Villaverde knew this would lead to the end of slavery and Cuban independence. Eager to help, she founded the club to motivate more women in New York to get involved in the independence effort and to raise funds to support the Cuban freedom fighters and their families (Boomer, 2022; Ruiz & Sánchez-Korrol, 2006). This led to Casanova de Villaverde becoming a very prominent figure during the war and effort for independence.

When Casanova de Villaverde discovered her father, a naturalized American citizen who also owned property in the United States, had been forcibly taken by the Spanish and held as a political prisoner in Cuba, she wrote to the United States Secretary of State, Hamilton Fish, asking for the American government to protect her father. She then traveled to Washington, D.C. where she met with many members of Congress and spoke with President Ulysses S. Grant in the White House (Boomer, 2022). She was the first Cuban woman to do this. President Grant was so moved by Casanova de Villaverde he ensured her father’s safe release from prison (Ruiz & Sánchez-Korrol, 2006). This was not the last time Casanova de Villaverde went to Washington D.C. in hope of gaining the help of the US government. In 1871, Cuban exiles learned that the Spanish had unjustly imprisoned Cuban medical school students in Havana. Casanova de Villaverde traveled to D.C. representing Cuban mothers and pleaded with Congress to help these students. Unfortunately, her efforts were ignored by Congress and the students were executed shortly after (Ruiz & Sánchez-Korrol, 2006). In 1872, Casanova de Villaverde returned to the U.S Capitol representing the Liga de las Hijas de Cuba to pressure Congress to recognize the hostilities Cubans were facing at the hands of the Spanish. She had evidence and openly condemned the United States for supporting Spain and preventing the abolishment of slavery on the island from the 1820’s-1850’s which in turn prevented Cuba from being liberated from Spain. Unfortunately her strong arguments did not gain U.S. support due to the financial advantage they had supporting a Spain-led Cuba. This did not discourage Casanova de Villaverde and she continued her work. Casanova de Villaverde used the network of underground tunnels and wine vaults in her fathers mansion as storehouses for rifles, guns, powder and ammunition which were bought with funds raised by La Liga de las Hijas de Cuba. The property spanned 50 acres, was very close to the coast and isolated making it perfect for using the Long Island Sound or East River to smuggle weapons to Cuba. Throughout the Ten Years’ War, Casanova de Villaverde ‘s home in New York was an important gathering place for the Cuban exile community. In 1873, a New York Times reporter visited her home and was met with many supporters of Cuban independence gathered there. Casanova de Villaverde had become an important and well known leader of the Cuban independence movement in New York. (Boomer, 2022).

“To the freedom of the world and to the independence of Cuba,”

~ Emilia Casanova de Villaverde (Ruiz & Sánchez-Korrol, 2006)

Analysis and Conclusion

Emilia Casanova de Villaverde passed away in 1897, only a year before U.S. forces got involved in the Cuban War of Independence in 1898 during the The Spanish–American War, successfully ending Spain’s rule over Cuba. Although she never saw Cuba be free of Spanish rule, her contributions and support helped the cause tremendously even in times of war, when women were expected to be passive. Casanova de Villaverde was an inspiration for generations of women who came after her to not be afraid to speak out for what you believe in as she accomplished many firsts. She was the first Cuban woman to write political essays, the first Cuban woman to travel to Washington D.C. and speak with a president, and she founded La Liga de las Hijas de Cuba, one of the first political organizations directed solely by women of New York. She and her Liga de las Hijas de Cuba in New York were the patriots needed in order to aid those fighting for independence in Cuba. With their aid they helped thousands of freedom fighters by smuggling weapons and ammunition into Cuba and supported hundreds of refugees, orphans, widows, and more who had fled from Cuba with nowhere to go. Emilia Casanova de Villaverde went against societal expectations of women being “lady-like” and docile and got as involved in the fight for independence as she could. Emilia Casanova de Villaverde’s courage and life-long determination to fight for Cuban independence will forever be remembered.

References

Boomer, L. (2022). Life story: Emilia Casanova de Villaverde. Women & the American Story. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://wams.nyhistory.org/industry-and-empire/expansion-and-empire/emilia-casanova-de-villaverde/#

Encyclopedia.com. (2022) Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/villaverde-cirilo-1812-1894

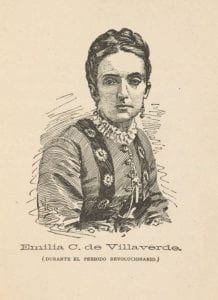

(Image) General Research Division, The New York Public Library. (1874). Portrait of Emilia Casanova de Villaverde Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/84c76cd6-50f4-8da3-e040-e00a18061c8e

Ruiz, V. & Sánchez-Korrol, V. (2006). Casanova de Villaverde, Emilia. In Latinas in the United States: A historical encyclopedia (pp. 125–126). essay, Indiana University Press.