Basic Information

Lucy Stone was an esteemed lecturer and supporter of abolition and women’s rights (Garvin, 2005). Playing a central role as an activist, she helped organize and run the first National Woman’s Rights Convention, the American Equal Rights Association, and the American Woman’s Suffrage Association. Stone was also well known for her audacious decision to keep her maiden name in marriage, inspiring other women to do the same.

Background Information

Lucy Stone was born on August 13th, 1818, one of nine children (McMillen, 2015, p. 1-62). She grew up on a thriving family farm in rural Massachusetts. From a young age Lucy worked alongside her siblings doing farm work and household chores, even making shoes. Her interests in reform and activism were initially inspired by her family life. Stone’s grandfather was a captain in the American Revolution. Her protestant Euro-American family were abolitionists, though her father maintained the dominance and superiority of men. Compared to her brothers, Lucy received little support from her father in academics. By the age of sixteen she was working as a teacher to fund her personal pursuit of higher education. Without the initial support of her father, it took nearly a decade to achieve her goal. She graduated from Oberlin College at 29 years of age. It was at Oberlin that Stone first discovered her affinity for public speaking, for which she was later recognized.

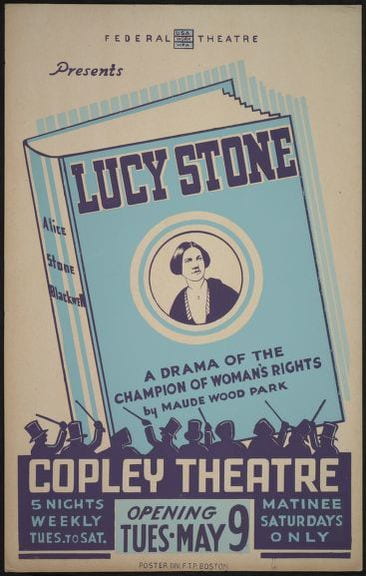

In her youth, Lucy showed a fervent reluctance towards marriage (McMillen, 2015, p. 114-148, 248). Nevertheless, at the age of 37 she married Henry Blackwell, after much coaxing. Their only daughter together, Alice Stone Blackwell, shared both of their names. After more than 45 years of dedication to the women’s movement, Lucy Stone died in October of 1893, relaying her final wish to her daughter: “Make the world better” (McMillen, 2015, p. 248).

Contributions to the First Wave

Lucy Stone made numerous contributions to the first wave of feminism, comparable to those of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton: first by making waves as a public speaker on both women’s and African American rights; and further acting as a leader in helping to create and oversee several organizations (McMillen, 2015). Moreover she pushed the boundaries of what is possible for women.

Stone is most well known as an orator, giving speeches and lectures on women’s rights and abolition throughout her life (McMillen, 2015, p. 63-89; Spruill, 2021, p. 190). After college she made a living doing lecture circuits around the U.S. and Canada, on the part of anti-slavery societies. Despite criticism, Stone was always able in her lectures to connect the two causes most dear to her. Nonetheless she gained recognition rapidly, for her words struck a chord with listeners as was the case with the speech that she delivered at the first National Woman’s Rights Convention, which some attribute as the catalyst for Susan B. Anthony’s commitment to women’s suffrage (Garvin, 2005). Elizabeth Cady Stanton even described Lucy Stone as “the first person by whom the heart of the American public was deeply stirred on the woman question” (Folsom et al., 1925, p. 492).

Lucy Stone played a crucial role in the organized efforts of the movement as well, helping with the creation and administration of several associations and proceedings. For example, she was part of the group of women who organized the first National Woman’s Rights Convention in 1850 (Garvin, 2005; McMillen, 2015). Supporting enfranchisement for both African Americans and women, Stone served as executive officer for the American Equal Rights Association, which she helped found in 1866. In the following year she helped organize the New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association, where she acted as president until moving to Boston. Soon thereafter, she was appointed to the executive committee of the New England Woman Suffrage Association. Stone was an active if not integral participant in these organizations, helping to organize conventions, rally members, raise funds, distribute petitions, lobby state legislatures, carry out campaigns, and give lectures.

During the post civil war schism that split the women’s suffrage movement in two, Stone and her husband created the American Woman’s Suffrage Association, rivaling Anthony and Stanton’s National Woman’s Suffrage Association (Garvin, 2005; Spruill, 2021, p. 189-208). Unlike their counterpart, the AWSA supported the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment (which would enfranchise black men) despite its explicit exclusion of women. The AWSA also differed in their strategy favoring a state-by-state approach towards women’s suffrage, compared to the NWSA’s national approach. While their efforts were arduous, they managed to achieve full or partial suffrage in some states such as Wyoming, Utah and Vermont. This approach would eventually prove helpful in the state’s ratification of the 19th Amendment, enfranchising women. As part of the AWSA, Lucy Stone and her husband also edited and published the Woman’s Journal, a weekly periodical on women’s rights and issues, featuring many pre-eminent writers of the time (Garvin, 2005; McMillen, 2015, p. 190). The journal garnered exceeding recognition and had a profound impact on the movement. Carrie Chapman Catt even argued that the realization of women’s suffrage was “not conceivable without the Woman’s Journal’s part in it” (McMillen, 2015, p. 190).

Stone’s feminism went beyond organized efforts as she tried to break barriers and elicit change on a personal level. For instance, in 1847 she was one of the first women in the U.S. to earn a bachelor’s degree and the first woman in Massachusetts to do so (Garvin, 2005). In 1858, she protested women’s unconstitutional lack of representation, by refusing to pay property taxes, resulting in the seizure of some of her household goods (Garvin, 2005; Wagner, 2021, p. 86-92). Stone was also the first woman in the country to keep her maiden name after getting married, refusing to be addressed by her husband’s surname. Many women took after her example, earning the moniker “Lucy Stoners”.

“We are lost if we turn away from the middle principle and argue for one class…Woman has an ocean of wrongs too deep for any plummet, and the negro too, has an ocean of wrongs that cannot be fathomed…I will be thankful in my soul if any body can get out of the terrible pit. “

~ Lucy Stone (Wagner, 2019, p. 207-208)

Analysis and Conclusion

Lucy Stone truly stands apart from her notable peers in the movement, in that she was able to rise above some of the common biases of the time and focus on the bigger picture – equality and suffrage for all. In contrast, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton had difficulty overcoming their own prejudices and self-interests. Namely, they refused to support the Fifteenth Amendment, because it enfranchised black men before themselves, ultimately forsaking the very people they had supported only years earlier (Cahill, 2020, p. 17). The fact that Stone refused to embark on the same campaign as her respected peers, is a testament to the strength of her convictions and integrity. Her promotion of the Fifteenth Amendment also demonstrates her ability to support and uplift other voices, even when it did not directly benefit her. We also see this with her publication of the Woman’s Journal, showcasing columns on black women and women’s issues around the world (McMillen, 2015, p. 192-193).

While Stone’s work with the AWSA yielded little results in terms of state voting rights for women (Spruill, 2021, p. 189-208), they did lay down the foundations that would later support the state’s ratification of the federal amendment, giving women the right to vote. It is hard to ascertain whether the measure would have been as successful without the groundwork the AWSA had done decades prior.

What is also notable about Stone is that she didn’t just speak about the changes she wanted to see in the world, she was active in trying to realize those changes. Even in her own personal life she tried to embody the principles for which she stood. Rejecting women’s perceived inferiority, she pursued higher education for herself and was one of the first women in America to graduate from college (Garvin, 2005; McMillen, 2015). We see this in her marriage to Henry Blackwell as well. Aiming to epitomize an egalitarian marriage, Stone excluded submissive language from her wedding vows, like “obey” (Garvin, 2005; Wagner, p. 91-93). Moreover, she set a precedent by refusing to take her husband’s name in marriage. In doing so she demonstrated that women don’t nor shouldn’t have to give up their identity or ownership over themselves in marriage. With these actions, she forged a new path forward, one that other women could follow.

In conclusion, Lucy Stone’s part in the first wave of feminism was invaluable. Despite the backlash and criticism she faced, Stone persevered as an orator, moving many to the cause of women’s suffrage (Garvin, 2005). She was dedicated to working towards both women’s rights and African American rights, refusing to pick sides at a pivotal moment in American history; a feat that some of her Euro-American peers struggled with at the time. Lucy Stone was a leader in many ways, from the work that she did with several associations to helping organize women’s rights conventions, as well as, pushing boundaries and leading a path of change by example. Her legacy continued with her daughter Alice Stone Blackwell, who carried on the Woman’s Journal and contributed to the unification of the NWSA and AWSA (Garvin, 2005).

References

Cahill, C. D. (2020). Recasting the vote: How women of color transformed the suffrage movement (Kindle Ebook). University of North Carolina Press.

Folsom, J. F., Fitzpatrick, B., & Conklin, E. P. (1925). The municipalities of Essex County, New Jersey, 1666-1924 (Vol. 2, p. 492). Lewis historical publishing Company. Retrieved October 24, 2022, from https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=lioXAAAAIAAJ&rdid=book-lioXAAAAIAAJ&rdot=1

Garvin, M. (2005). Lucy Stone. Great Neck Publishing. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://web-s-ebscohost-com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/ehost/command/detail?vid=5&sid=9d30d4fb-84cf-422d-9961-711df01366b9%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#jid=TWE&db=ulh

Lucy Stone, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right. (1840-1860). [photograph] Retrieved from Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/97500092/

McMillen, S. G. (2015). Lucy Stone: An unapologetic life. Oxford University Press. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/lib/washington/detail.action?docID=1890733#

Park, M. W. (1934-1943). Lucy Stone a drama of the champion of woman’s rights. [Photograph] Federal Theatre Project 1934-1943. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/musihas.200216466/

Spruill, M. J. (Ed.). (2021). One woman, one vote: Rediscovering the woman suffrage movement (2nd, Ebook). NewSage Press.

Wagner, S. R. (Ed.). (2019). The women’s suffrage movement (Ebook). Penguin Classics.