July 9, 2020

Economic Growth and Increased Productivity is Only Half the Battle, By Taylor D.H. Rockhill

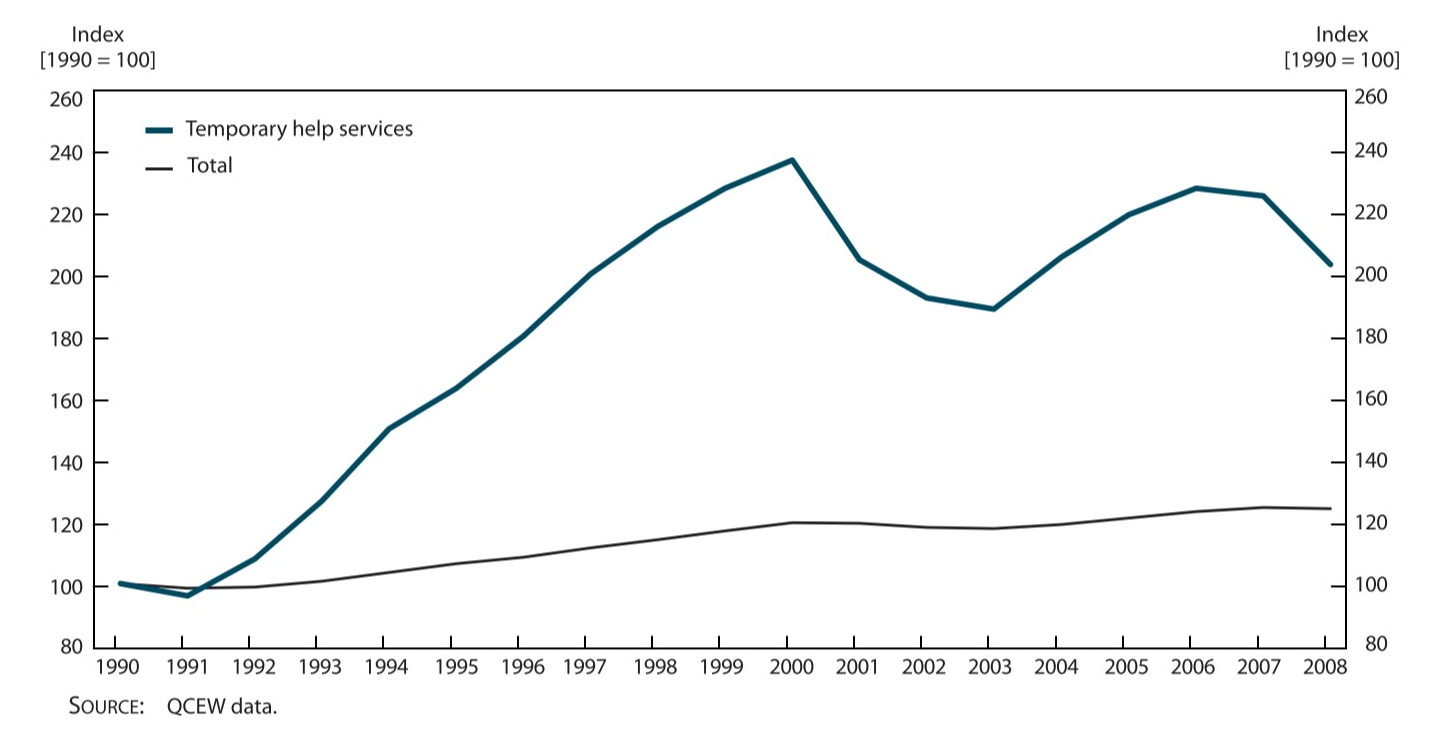

My career as an economist started nearly a decade ago, under the watchful eye of the inimitable Deirdre McCloskey. I still fondly remember reading her beautifully written, formidable Bourgeois trilogy and wondering: will I ever come close to attaining her seemingly bottomless well of knowledge? I highly recommend her Bourgeois books, Cult of Statistical Significance, and Economical Writing to both new and established economists. In my early days, however, I also took a course on the history of economic crashes, up to and including the 2007/08 crash, which back in 2010 was still quite fresh. It was during that course that my economist’s version of an existential crisis began; it all started with this one chart:

Now, let me explain the crisis: I come from modest beginnings, a working-class family that, like many other working-class families, was left behind by the emergence of Neo-liberal economics (Thatcherism/Reaganomics by any other name) in the late 1970s. This, as well as Deirdre, was one of the things that made me want to become an economist. Reading the Bourgeois trilogy and soaking up the emergence and history of the British, Dutch, and American middle classes was enlightening, even life-defining; it made economics exciting.

Growing up working-class was not ideal. My therapist and I frequently discuss the ‘trauma of poverty’. Deirdre posits that bourgeois shopkeepers and innovators, the commercial and political engine of economic productivity and sustained growth, were the key to helping societies escape poverty. The take-away, for me at least: an economist should help make the middle class as large as possible and do everything imaginable to improve the life of the working class. That damned chart showed that the middle class was not growing though. In the United Kingdom, the United States, and India, economist Amartya Sen’s rising tide was not helping to lift a pretty big boat. What was I to make of this?

It is no secret that Millennials are the most un- and underemployed generation in recent history. They are also the most indebted and have the lowest savings. Statistically, they are the first post World War II generation to be worse-off than the previous one. In terms of GDP and even GDP Per Capita, the pie obviously continues to grow–at least till Covid-19 hit. Much less obvious, however, is how big the individual slices are. For many of my colleagues, unemployment and underemployment are entirely theoretical. Many of my colleagues are the children of academics and white-collar professionals; they have never had to live through chronic unemployment or underemployment. For many of these colleagues, the response to the malaise affecting large chunks of the labor market is, “in the long run it will all work out”. However, to quote Keynes, “in the long run we are all dead”. The immense economic pain that has been felt by many during the Covid-19 crisis is symptomatic of the same disease we saw, and left largely unaddressed, in 2007. Wages are stagnant, savings are non-existent, and cheap credit, whilst appeasing, is hardly a cure. Aside from the aesthetic pleasantries offered by a select few macroeconomic statistics, the economy is sick, and it is getting sicker.

In the midst of this growing crisis is the rise of temporary labor. Luo et al (2010) found that, as early as the 1990s, the growth of temporary labor outpaced the growth of more stable ‘traditional’ employment:

Temporary labor has been favored by employers because it has allowed them to access the labor market without having to provide benefits or higher salaried wages. The rise of temporary employment agencies in the 1990s also helped the practice flourish, especially the outsourcing of costly HR tasks to third party specialists. Temporary labor, however, as its name implies, is temporary and paid by the hour. It is less reliable than traditional salaried employment. It has become the mainstay for Generation X workers and their Millennial counterparts.

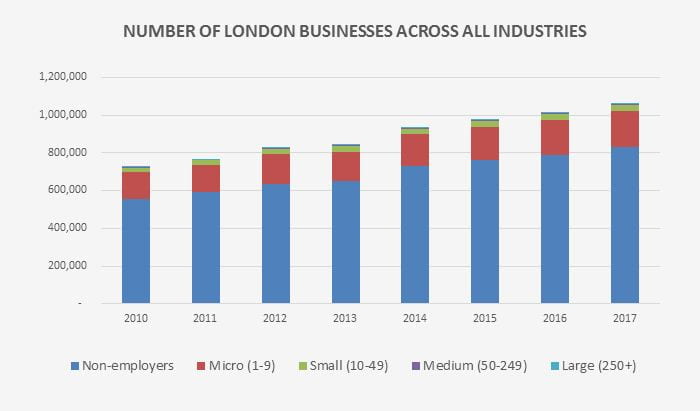

Many countries’ labor bureaus and statistical agencies are grappling with how to measure the growing “gig economy”. Kässi and Lehdonvirta (2018) make a valiant attempt using a supply-side method: by looking at the size, in users, of popular “gig economy” platforms such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk or fiverr. In the United Kingdom, the gig economy can be measured imperfectly by looking at the share of companies that are so-called non-employers. It turns out these “non-employers” are starting to dominate London’s economy; the chart below shows but one example, in one sector, of a larger trend.

This is problematic because historically these ‘gig-economy’ jobs have not paid as well as traditional arrangements. Uber, Deliveroo, Bolt, Ola, and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk have all come under fire for skirting established minimum wage laws by designating their workers “independent contractors” rather than employees. In 2018, Americans on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk averaged only $0.40/hour. Adding insult to injury, as “five-star” review systems replace traditional employee reviews, “independent contractors” face potential unemployment if a fickle customer awards them a 1-star rating. Indeed, several customers of gig economy services have been caught giving 1-star ratings simply to get discounts.

As we increasingly rely on these ‘gig economy’ employers, we also unleash a threat to existing welfare systems. Consider the United States, where healthcare is still tied to employers. While in the UK this problem is mitigated by the National Health Service (NHS), these types of programs are financed by governments that collect revenues through taxation, a lot of it on ordinary business activity. But what happens when gig-economy providers like Amazon fail to pay adequate taxes and displace other employers who do? It potentially undercuts the state’s ability to effectively address the negative impacts on healthcare and housing caused by increased underemployment.

The rise of temporary labor has pushed wages down for blue collar workers. As computers get better at pattern recognition and rapid decision making, it will impact middle-skill, middle-income jobs. The jobs will be replaced, yes, but if current trends are anything to go by, they will be replaced with low-skilled, low-income jobs. The digital revolution is transforming our modern economy in ways comparable to the way the industrial revolution transformed the economy of 18th century Britain and 19th century America.

This is where I turn back to my ‘McCloskey impulse’ to examine economic history. The 40-hour work week, the minimum wage, the office, holidays versus working days, university education, and the idea that we even have “jobs” or “careers” are all byproducts of the industrial revolution. If we traveled back in time, to Britain prior to the civil wars (1640-1660), we would find an entirely different economy built around agriculture. That is, entirely built around a few labor-intensive tasks such as planting in spring and harvesting in autumn. The modern week, the modern holiday, the modern workflow is just that—modern.

We are at potentially at a similar inflection point in labor markets and attendant social institutions now. AI is going to change the way our economy is structured again. Whereas the industrial economy was reliant on industrial labor, we may have to conceive an economy that is not as reliant on labor, and if not reliant on labor, it cannot be reliant on wages. At least not in the current way we understand wages.

There is nothing wrong with a future of increased freedom from work, and indeed from what David Graeber calls ‘bullshit jobs’ in the eponymous book. That was always the hope, one shared by John Maynard Keynes. But there is something wrong with an economic system that allows a diminishing few, in a diminishingly few cities, in a diminishingly fewer nations, to enjoy the full fruits of the increased productivity. Hopefully economists can help find ways to right the ship.