The Howard Hughes Medical Institute has supported biomedical research for nearly 70 years, and for most of that time, at least one HHMI Investigator has called our department home. Our crop of Investigators grew this year when David Veesler, associate professor of biochemistry and virologist extraordinaire, was invited to join the prestigious program.

“I was probably one of the few people in the world who interviewed wearing shorts,” said Veesler. On the day of his Zoom call, it was 106 degrees in Seattle.

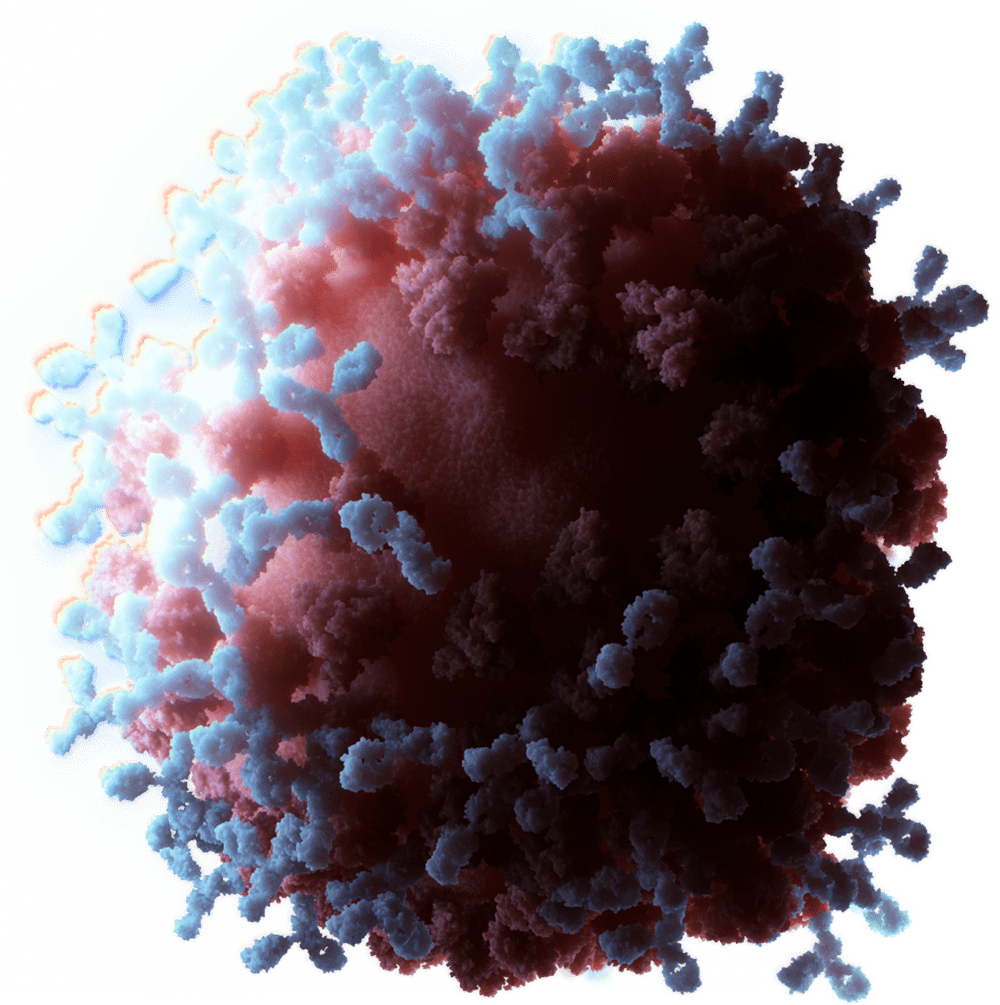

Few scientists will ever have their field of study thrust into the spotlight like Veesler. For years, his laboratory at UW Medicine has researched coronaviruses. Using advanced electron microscopes, they were the first in the world to obtain an atomic-level description of how coronavirus proteins bind human cells to kickstart infection.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the Veesler lab was ready.

In just weeks they revealed the three-dimensional structure of the novel coronaviruses’ spike protein and, with collaborators in the King lab at the Institute for Protein Design, helped create a candidate vaccine that is now in the final stage of human clinical testing. If proven safe and effective, it could be administered to millions around the world.

The Veesler lab also helped identify powerful neutralizing antibodies in the blood of recovered COVID-19 patients. These broad-spectrum antibodies are now being formulated as drugs to treat multiple strains of the virus, including the new Omicron variant.

“The pandemic has propelled our scientific work, and we are making discoveries related to COVID-19 every week, but that’s not what I proposed to do with HHMI funding,” said Veesler. “With HHMI, you need to propose game-changing research in new and exciting directions. Right now, half of the planet is working in our field. So to set us apart, I proposed two new areas of study for my lab.”

The first is to delve into growing DNA sequence databases in order to spot viruses that may cause problems in the future. “There are thousands and thousands of viruses out there, but which ones should we care about?” asks Veesler. With backing from HHMI, his lab will now seek to develop high-throughput methods to identify viruses in bat populations that might one day leap into humans.

Another area of study asks: what’s so special about bats? “No one has really looked at bat antibodies,” explains Veesler. “How do they keep those animals from getting sick from viruses that can be so deadly for us?”

Veesler believes that without the flexibility afforded to him by HHMI funding, he would not be able to pursue either area of research.

A scientist with seven lives

As Veesler was preparing his HHMI application, he turned to a departmental colleague for advice. “He asked me to look at his video proposal,” said Richard Palmiter, a 46-year HHMI veteran, “and I gave him a little feedback along the way.”

Palmiter became an HHMI Investigator in 1976. He recalls that the initial decision of whether to accept the honor — and the funding — was far from simple. In those days, HHMI Investigators received support in the form of salary for five years, but doing so could interfere with one’s ability to secure tenure. “I was concerned,” said Palmiter, “but I took the gamble.”

That decision almost 50 years ago paved the way for a sterling career marked by bold transitions in both subject matter and research methods.

“I think I’ve had seven scientific lives,” he said. “We started off studying growth, then cancer, then cell-specific enhancers. We’re essentially neurobiologists now. That, on an NIH system, wouldn’t be impossible, but it would be much more difficult.”

Advice for new and future Investigators

Veeser’s advice to those who may may apply for HHMI funding in the future is to do what he did — turn to the Investigators around you.

“Richard had some big-picture advice that was helpful, but he also shared some specific feedback about sections of my application that were not clear to him. This was very valuable as HHMI review panels are made up of researchers from many different disciplines. I figured if something’s not clear to Richard, I should fix it.”

Palmiter’s advice to young scientists who receive flexible support is simple: “Pick interesting projects that are bigger than you and pursue them aggressively. Always follow your nose.”

When it comes to applying for funding, “make the story as interesting and as simple as possible,” said Palmiter. “The excitement of the research is the most important thing.”