(University of Washington Society and Culture Digital Collection)

A Curriculum Project for Washington Schools

Developed by

Matthew W. Klingle

Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest

University of Washington Department of History

Curriculum packet PDF

One story of Washington state is a story of immigration, but it is not the simple tale of assimilation or acculturation. Immigrants brought pieces of culture from their native lands to Washington state, where they melded them with pieces taken from American culture. Immigrants did not remain unchanged or melt into a common society, however. Instead, Washington is a mosaic made of different peoples coming together to create new lives in a new land. The Asian American experience is part of this mosaic. The documents that accompany this essay demonstrate how Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos came to Washington, struggled against discrimination, labored to earn their living, and created distinctive cultures and identities. These documents chronicle, in a small way, how some Asian immigrants became Asian Americans. “Asian American” is, by necessity, a broad term that lumps different peoples together. Because of space restrictions, this project focuses on Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino Americans, the three largest and oldest groups in Washington. Other groups, notably immigrants from Korea, the Pacific Islands, and Southeast Asia, receive limited attention here. It is hoped that students and teachers alike will use this project as a guide for building their own collections on other Asian Americans.

The documents are organized by three general themes: migration, labor, and community. Migration is the process of people moving from place to place. Why people move away or are pushed out from where they lived, and why they are pulled to settle somewhere else, are the central questions behind migration. Once in the United States, Asian immigrants often migrated to and from places of work; others, after living abroad for a time, returned to their native lands. Asians, like all immigrants, were a people in motion. Labor refers to the act of working and the social associations that workers create through their shared experience. Most Asians came to Washington state to fill a need for workers in the rapidly developing Pacific Northwest. Limited by discrimination and economic factors, Asian immigrants often worked menial jobs in hazardous industries for little compensation. But work was also a source of group pride and political activism; labor was a catalyst for social and cultural change. Community stands for how Asians and Asian Americans struggled to define their social and cultural place in the larger American society. The creation of community is not a simple process, however. Generational tension, racism, and economic concerns all worked to pull Asian and Asian American communities apart. But these communities, like other immigrant groups in U.S. history, responded creatively to hardship. Applying for U.S. citizenship, opening businesses, running for political office or lobbying for social services are just some of the ways that Asians and Asian Americans worked to create dynamic communities in Washington state.

What follows is a brief overview, written to help teachers navigate through this material. Those interested in learning more should consult the bibliography for appropriate books and resources. A timeline of significant dates in Asian American history, with a focus on Washington state, also follows. Additional details for specific documents are provided in the concordance and index included here.

Migration is one theme that unites the histories of Asian American peoples in the Pacific Northwest. Like immigrants from Europe during the nineteenth century, Asians were part of a global stream of people flowing into the United States. While Asian immigration reached its high-water mark on the West Coast, it transformed America, adding diversity to an already multicultural society.

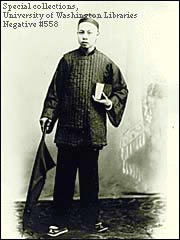

The Chinese were the first Asians to migrate in significant numbers to Washington state. In the mid-nineteenth century, China seemed on the verge of collapse. The Taiping Rebellion nearly tore Chinese society apart, British warships devastated China’s major ports during the Opium War, and periodic flooding and famine wrecked the countryside. South China, primarily the area around Guangzhou (Canton), suffered the most; and it was from here that the vast majority of immigrants came. Initially drawn to work in California’s gold fields or Hawai’i’s sugar plantations, Chinese were also drawn to work in the Pacific Northwest. By the 1860s, news of a gold strike in eastern Washington brought Chinese immigrants here; by the 1870s, Chinese were recruited to work on railroad construction as well as in logging camps and salmon canneries. Immigration was illegal before the 1868 Burlingame Treaty, but labor contractors and immigrants conveniently ignored such restrictions.

Similar push and pull factors drew Japanese immigrants to Washington state. Following the forcible opening to Western trade in the 1850s, Japanese society underwent wrenching economic and cultural transformations. The Meiji government, bent on industrializing the country as quickly as possible, adopted policies that forced Japanese farmers off of their lands, forcing many to work as migrant laborers on Hawai’ian sugar plantations. By the mid-1880s, Hawai’i relied heavily on Japanese contract labor. After Hawai’i was annexed by the United States in 1898, and after the passage of the Organic Act in 1900 that created the Territory of Hawai’i, many Japanese living on the islands traveled to the mainland. Others, driven out by worsening economic and social conditions at home, attracted by high pay and a demand for labor in the Pacific Northwest, followed directly from Japan. Like the Chinese before them, Japanese migrants picked produce, cut and milled trees, built railroads and butchered fish.

Filipinos, who arrived in the third wave of Asian immigration to Washington, were a comparatively unique case. The Philippines were an American colony, acquired after the 1898 Spanish-American War, and remained under American jurisdiction until after World War II. Filipinos were recognized as U.S. nationals, a status just below full citizenship, and allowed to migrate anywhere within the states. As with the Chinese and Japanese, Filipino migrants were pushed out by economic hardship at home and pulled to migrate by economic opportunity abroad. Changing land tenure patterns following U.S. annexation limited prosperity in the Philippines, and labor remained in short supply in the Pacific Northwest. Moreover, Filipinos educated in American-run schools after the war considered themselves American and entitled to all the privileges that entailed. Filipino women married American soldiers and returned with their husbands to the United States; other Filipinos came for jobs in agriculture and the salmon fisheries. By the 1920s, Filipinos were a major segment of Washington’s Asian American population.

For many Asian immigrants, working and living in Washington state was a temporary condition. The first wave of Chinese migrants, almost exclusively men, called themselves sojourners; they came to earn income, then return to China with their earnings. Early Japanese and Filipino migration followed a similar pattern. But economic hardship in the United States, together with restrictive labor contracts and new commitments in America, compelled many to stay. The pull of remaining in their new home often overwhelmed the tug of returning to their native country. And for nearly every immigrant who stayed, the opportunity to work in the United States was a major reason why they made their home here.

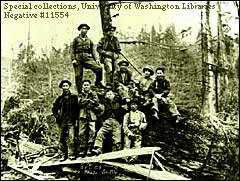

Labor is another theme that characterizes the Asian American experience in Washington state. Asian immigrants filled an important need in the resource rich but labor poor Pacific Northwest, providing the muscle that helped to develop the region. Indeed, without Asian labor this region would have remained isolated, undeveloped, and poor well into the twentieth century. Asian immigrants helped to create the transportation links, industries, and wealth that made the Pacific Northwest.

Mining was one of the first industries to employ the Chinese, who prospected for gold along the Columbia River in eastern Washington and hauled coal from pits in Black Diamond, Newcastle, and Renton in western Washington. Chinese laborers also built rail lines that connected the territory to eastern markets; indeed, the Chinese were instrumental in building almost every major rail connection in Washington before 1900. Likewise, Japanese migrants worked on the railroads, first in construction, later as porters and foremen.

Community is a broad theme that encompasses both the hostility Asians faced by white society as well as their ability to create new societies in the United States. It is the process by which Asians identified themselves as Americans. Ironically, this process begins with discrimination. Singled out by white Americans because of their putative “racial” characteristics, Asians relied on their own institutions and initiative to advance their interests. In resisting discrimination, Asians found opportunities to build community—and opportunities to claim America as theirs.

Asian immigrants faced discrimination almost upon arrival in the Pacific Northwest. In 1853, the newly created Washington territorial legislature barred Chinese from voting; later legislation enacted poll taxes and restrictions on testifying in court cases against whites. These laws were modeled on similar legislation in California (which remained the most popular destination for Chinese immigrants well into the late nineteenth century). As agitation against the Chinese escalated on the West Coast, national lawmakers began to take notice. Eventually, Congress, bowing to public pressure and prevailing racial stereotypes, acted to limit the immigration of Chinese labor.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 set the tone for later laws designed to exclude further Asian immigration. It also fundamentally altered the shape of Asian communities in the United States by banning women immigrants. By 1890, the ratio of men to women among Chinese Americans nationwide was approximately thirty to one; not until 1940 would the ratio drop to less than two to one. In Washington state, the Exclusion Act permanently stunted Chinese American communities, which were never able to rival similar groups in San Francisco or Vancouver, British Columbia. The Exclusion Act became an instrument of violence against Chinese. The anti-Chinese movement that swept across the American West was especially extreme in Washington. An economic depression in the mid-1880s, which left white workers competing for dwindling jobs, fueled animosity. In 1885, white Tacoma residents expelled 700 Chinese (some forcibly) from that city and torched Chinese residences and businesses; the next year, Seattle residents hauled their Chinese neighbors by wagon to waiting steamers. Elsewhere, whites attacked Chinese in Walla Walla and Pasco.

Japanese and Filipino immigrants became the next targets. Since 1789, nonwhites from overseas could not become citizens; the question now swung on who could immigrate to the U.S. The 1907-08 “Gentleman’s Agreement” between Japan and the U.S. prohibited further male immigration but allowed in women, along with relatives and children of Japanese aliens living in the United States. The category “aliens ineligible to citizenship,” dating from 1789, used race to restrict naturalization. The 1924 National Origins Act, which distinguished Asians from other immigrant groups, extended this logic and further restricted all Asian immigration. The 1924 law left the door open for Filipinos, however, who were U.S. nationals. But the new act severely limited Japanese and Chinese immigration for over four decades. Upheld by legal precedent, the 1924 act had local effects on Asians living in Washington. The 1889 state constitution, in Section 33 of Article II, already prohibited resident aliens from owning land. In 1921 and 1922, the rule was extended to leasing, renting, and sharecropping of land. The 1924 Act sanctioned further discrimination, especially against the growing Filipino population. Filipinos themselves were the object of racist fears over mixed marriages and dwindling jobs. In 1927, whites expelled Filipino farmers from Toppenish in the Yakima Valley. In 1933, white farmers and workers in Wapato demanded that area growers stop hiring Filipino workers.

Again, as with the Chinese and Japanese, federal action spurred greater discrimination in the states. Filipino immigration was virtually stopped in 1934 by the Tydings-McDuffie Act, which made the Philippines a commonwealth and promised full independence within a decade. Filipinos, now defined as resident aliens, were limited to a quota of fifty annually. But attacks and recrimination against Filipinos did not end there. Filipinos, who married white women in numbers larger than their Chinese and Japanese counterparts, aroused the ire of whites obsessed with racial purity. In 1937, the Washington Legislature tried to pass a law banning mixed race marriages. Filipinos were added as resident aliens under state law in 1938; and the anti-alien land laws directed against them and other Asian Americans were not repealed until 1966.

Perhaps the ultimate expression of racial fears against Asians was the internment of Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War II. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, bowing to public pressure on the West Coast, signed Executive Order 9066, calling for the removal of all persons of Japanese descent from coastal areas (except Hawai’i). Claiming military necessity, Japanese and Japanese Americans were forcibly expelled from their homes and businesses; no action of similar magnitude was taken against German Americans or Italian Americans. Most of those evacuated were American citizens, born in the United States and fully entitled to constitutional rights and privileges. Most Washington residents were relocated to Minidoka located near Hunt, Idaho; other West Coast Japanese went to inland concentration camps in California, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, Arizona and Arkansas. Japanese internment did not go unchallenged, however. Gordon Hirabayshi, a University of Washington student, was charged with resisting evacuation orders; his conviction was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1943. But despite the obvious injustice of internment, many American-born Japanese, known collectively as “Nisei,” volunteered for combat duty in Europe. The all-Nisei 100th Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team were some of the most highly decorated units in American military history. Yet not until 1988 did the federal government apologize and remunerate internee survivors and their families.

Even under the harsh circumstances of concentration camps, Japanese Americans relied on community organization to endure. Interned Japanese formed consumer cooperatives, baseball teams, and literary societies. Such responses were rooted in long-standing experience with adversity. Prior to the war, Japanese in Washington came together through kenjinkai, social associations that drew members who came from the same village or county in Japan. Kenjinkai helped new immigrants find jobs, make business contacts, and practice speaking their native language. Local branches of the Japanese Association of North America ran Japanese language schools. Most of these organizations catered to the foreign-born generation, or Issei. American-born Japanese, or Nisei, established the Japanese American Citizens League to promote unity and lobby for civil rights. Sports, too, were another part of the Japanese community network, with baseball a widely popular pastime. Japanese communities throughout the Pacific Northwest fielded baseball teams and played against white competitors. Religion played a part, too, as Christian and Buddhist churches provided spiritual and social comfort.

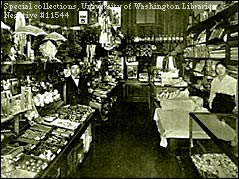

The Chinese, though smaller in number, also relied on community organizations to strengthen ethnic ties in Washington. Family associations, district associations similar to the kenjinkai, and tongs (secretive fraternal orders that also served as trade guilds) formed the framework of the Chinese community. Concentrated primarily in Seattle, benevolent family associations like the Gee How Oak Tin offered business loans, language instruction, and social activities to eligible members. In 1910, Seattle Chinese chartered the Chong Wa Benevolent Association, a coalition of local groups and businesses, to administer Chinatown politics and support Chinese causes. Prominent businessmen like Chin Gee Hee and Ah King, both labor contractors, protected new immigrants while establishing important ties with white Seattle elites. And churches, notably the Chinese Baptist Church on Seattle’s First Hill, also served to unite immigrants and older residents through ministry and community outreach.

Filipinos, largely comprised of bachelors, also found community through adversity. Large groups of single men created new “families” based on local affiliations from the Philippines. Often, Filipino women served as surrogate mothers, aunts, and sisters for men with no immediate family in the United States. Filipinos were also active in the labor movement, organizing unions to protect their interests. The harsh conditions of canning salmon inspired Filipino workers to form the Cannery Workers’ and Farm Laborers’ Union Local 18257 in Seattle in 1933. One of the most militant unions on the West Coast during the Depression, the CWFLU struggled to shield Alaskeros from exploitation. Unions and social clubs also fought against restrictive land and property laws. The Filipino Community of Yakima County, Inc., after protracted battles, eventually secured leasing rights on the Yakima Indian reservation, a privilege already granted to whites. In 1939, Pio DeCano, a recent immigrant, successfully fought the 1937 Washington state alien land law all the way to the state Supreme Court. Perhaps more than any other Asian immigrant group, Filipinos made their greatest gains through legal challenges and union organization. And as with other Asian communities, religion, notably the Roman Catholic Church, drew Filipinos together in a common faith.

The postwar period saw the beginnings of a newer sense of identity, however, one based on a hybrid sense of Asian and American heritage. In 1952, immigrants were allowed to become naturalized citizens but restrictions against Asian immigration remained. Reforms to immigration law, culminating in the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, spurred a sharp increase in Asian immigration. Newer immigrants from Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands added greater complexity to Washington’s Asian community. New faces forced old residents to confront the issue of who passed as American — and who passed as immigrant.

The civil rights movement, spearheaded by African Americans in the South, also affected ethnic politics in Washington state. In Seattle’s Central District, where Asian Americans and African Americans had lived in close proximity for nearly six decades, community leaders crossed ethnic lines to fight together for public housing, tenant rights, election reform and employment opportunities. While ties between Seattle’s Black and Asian communities frayed by the late 1960s, the city was unique on the West Coast for its multiethnic civil rights campaigns. Asian Americans, long stereotyped as passive laborers, also made political inroads of their own as well. They became an increasingly vocal constituency in Washington state politics. In 1963, Wing Luke became the first Chinese American elected to the Seattle City Council; Ruby Chow, the first Chinese American woman, was elected in 1973; and in 1996 Gary Locke, then King County Executive, was elected as the first Chinese American governor on the mainland United States. Such victories were made possible by political coalitions that united Asian Americans of all orientations. In political as well as cultural terms, Asians began referring to themselves as Asian Americans, or Asian/Pacific Americans, reflecting an identity that transcended previous ethnic bonds.

But the growing diversity of the Asian American community also threatened this communal harmony. Resettlement of Cambodians, Laotians, Vietnamese, and Hmong refugees introduced new problems. In 1960, two-thirds of the state’s Asian Americans were native born; by 1980, two-thirds were foreign born. Most of these refugees settled in areas with an established Asian presence, usually in Seattle, Tacoma, and the Yakima Valley. Fleeing war and extreme poverty, they faced the residue of anti-Asian feeling; moreover, they often faced resentment from those Asians already established in the United States.

Generational and class conflicts also divided and split communities. By the 1970s, Asian Americans nationwide were hailed as the “model minority” because of their academic achievement and gains in the workplace. But such gains often masked deep tensions between young Asian Americans, who seemed to assimilate fully into traditionally white institutions, and older Asian Americans, who worried about the survival of old ways and customs. The relative achievement of some also masked the difficulties facing newer arrivals from Southeast Asia, Korea, China and the Pacific Islands.

Despite such tensions, however, Asian American communities are indisputably central to Washington’s social and cultural fabric. Discrimination continues but its effects are blunted by the prominence of Asian Americans in business, politics, the arts and education. Compared to the blatant racism of a century earlier, Asian Americans have achieved remarkable gains. Still, the dynamics of community building continue. As before, the forces that rip communities apart also are the source for their renewal. Seen one way, divisions within the Asian American community over language instruction, immigration policy, and social welfare are tears in the social fabric. Seen from another angle, they are the seams that bind communities together.

Today, Asian/Pacific Islander immigrants and Asian Americans in Washington are citizens not sojourners. They have been and will remain an integral part of the state’s diverse history. Migration brought Asians to the Pacific Northwest, labor defined their social status while providing opportunities for advancement, and communities emerged out of struggles to preserve old customs in new places. While Asians faced persistent, often brutal, discrimination they were not merely victims. Instead, they made their own history and influenced the history of others. As scholar Ronald Takaki says, their “history bursts with telling.” These documents are only fragments of their stories.

Bibliography: Selected Books

Chan, Sucheng. Asian Americans: An Interpretive History (Boston: Twayne, 1991).

A solid general survey of Asian Americans, with a strong focus on Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino communities. Good discussion of gender and immigrant communities, but not as rich as Takaki for anecdotes and quotations.

Chin, Doug and Art Chin. Up Hill: The Settlement and Diffusion of the Chinese in Seattle, Washington (Seattle: Shorey Book Store, 1973).

One of the first works on the Chinese community in Seattle. While difficult to find in many libraries, it contains good information on the 19th century.

Cordova, Fred. Filipinos: Forgotten Asian Americans: A Pictorial Essay, 1763-1963 (Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt, 1983).

A general survey of Filipinos in the United States, with special focus on the Pacific Northwest and West Coast. Good for anecdotes, pictures, and quotations.

Daniels, Roger. Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States since 1850 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988).

Based on archival records and secondary literature, this is one of the better historical surveys available. Useful charts and maps show demographic changes and immigrant characteristics. Concentrates on the West Coast, with good material on Washington and the Pacific Northwest; but nothing on Filipinos in America. One of the first major works to dispel earlier scholarship characterizing Asian Americans as victims.

Daniels, Roger. Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans in World War II (New York: Hill and Wang, 1993).

One of the best short histories of Japanese internment. Probably suitable for upper-division high school classes.

Erickson, Edith E. From Sojourner to Citizen: Chinese of the Inland Empire (Colfax, Wash.: E. E. Erickson and E. Ng, 1989).

Locally-written history of Chinese on the Columbia River Plateau. Good anecdotal information and sources, but best used alongside one of the more scholarly surveys listed here.

Friday, Chris. Organizing Asian American Labor: The Canned Salmon Industry 1870-1940 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992).

The best book available on this important Pacific Northwest industry that relied on Asian American laborers. Strong, vivid descriptions of canning work coupled with detailed analysis of cannery life and union activities during the 1920s and 1930s.

Kim, Hyung-Chun, ed. Dictionary of Asian American History (New York: Greenwood Press, 1986).

Useful reference book for major dates, names, and themes in Asian American history. Best used in conjunction with one of the surveys listed here.

Melendy, H. Brett. Asians in America: Filipinos, Koreans, and East Indians (Boston: Twayne, 1977).

One of the few general surveys of Filipino Americans (as well as Korean Americans and East Indian Americans). Some material on Filipinos in Washington state, but best used in conjunction with Cordova’s book, which provides more anecdotes and visual material.

Nomura, Gail M. “Washington’s Asian/Pacific American Communities,” in Peoples of Washington: Perspectives on Cultural Diversity, edited by Sid White and S. E. Solberg. (Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1989), 113-156.

A very useful overview of Asian Americans in Washington state, commissioned for the centennial year celebration.

O’Brien, David J. and Stephen S. Fugita. The Japanese American Experience (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991).

A survey of Japanese immigration and Japanese American community building, with a strong focus on California. Some material on the Pacific Northwest and Washington state.

Okihiro, Gary. Margins and Mainstreams: Asians in American History and Culture (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994).

Okihiro argues that Asian American identity emerged from their position on the margins of American society. Their experience, he claims, has in turn shaped American notions of culture and democracy. Good for analysis of how Asian American identity emerged and changed over time.

Takaki, Ronald. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1989).

Another useful historical survey that also includes information on Korean, South, and Southeast Asian immigrants. Takaki quotes extensively from literature and oral interviews, making the book useful for anecdotes and examples.

Taylor, Quintard. The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994).

While Taylor concentrates primarily on Seattle African Americans, the book has information on the connections between Blacks and Asians. Also a useful model for thinking about how communities are created and changed over time.

Bibliography: Selected Videos

A Personal Matter: Gordon Hirabayashi vs. the United States. (San Francisco: CrossCurrentMedia/National Asian American Telecommunications Association, 1992). 30 min.

Documents the 43-year struggle of Gordon Hirabayshi, a Japanese American who challenged the legality of the 1942 evacuation order and subsequent internment.

East of Occidental. (Seattle: Prairie Fire, 1986). 29 min

A visual history of Seattle’s International District (formerly Chinatown) as told through interviews with local residents.

Dim Sum: A Little Bit of Heart. (Beverly Hills: Pacific Arts Video, 1987). 88 min.

Directed by Wayne Wang, this is a humorous look at how a contemporary Chinese American family in San Francisco negotiates living as Chinese in a white society.

Filipino Americans: Discovering their Past for the Future. (Seattle: Filipino American National Historical Society, 1988). 54 min.

Documentary survey of Filipino and Filipino American history in the United States. A good companion to Cordova’s book on the Filipinos cited above.

Home from the Eastern Sea. (Seattle: KCTS Television, 1989). 58 min.

A brief survey of the history, culture, and accomplishments of the Asian Pacific Islander communities in Washington state. A good survey designed for classroom use.

The Great Pinoy Boxing Era. (San Francisco: National Asian American Telecommunications Association/CrossCurrent Media, 1995). 32 min.

Documentary of the golden age of Filipino boxing during the 1920s and 1930s. Discusses how Filipino boxers changed Western boxing techniques and styles; and how they served as role models for the mostly male Filipino American community.

Slaying the Dragon. (San Francisco: National Asian American Telecommunications Association/CrossCurrent Media, 1984). 60 min.

Discusses the historical and contemporary experiences of Asian American women in the workplace, at school, and in their communities.

Who Killed Vincent Chin? (New York: Filmmakers Library, 1988). 83 min.

Documentary of the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin, a 27-year old Chinese American who was the victim of a racially-motivated attack in Detroit. An effective classroom tool for discussions of prejudice generally or anti-Asian, especially anti-Japanese, sentiment.

With Silk Wings. (San Francisco: National Asian American Telecommunications Association/CrossCurrent Media, 1984). 120 min.

Discusses the historical and contemporary experiences of Asian American women in the workplace, at school, and in their communities.

Yellow Tale Blues. (New York: Filmmakers Library, 1990). 30 min.

Short documentary of Asians living in America through interviews with two families interspersed with images and stereotypes of Asians as portrayed in popular culture and film.

Community Resources (Seattle)

DENSHO: The Japanese American Legacy Project

A digital archive of video taped interviews, photos, maps and other historical documents on the pre- through post-war Japanese American experience.

Filipino American National Historical Society

Located in the Central District, FANHS holds the largest collection of Filipino and Filipino American documents, oral histories, and ephemera on the West Coast. A good source for materials and information on Filipinos in Washington state.

National Archives and Records Administration

Chinese Immigration and Chinese in the United States

Records in the Regional Archives of the National Archives and Records Administration. Compiled by Waverly B. Lowell. Reference Information Paper #99, 1996.

This document summarizes the various records available in the National Archives where information on the Chinese is found. Government agencies included are: District Courts, Bureau of the Census, U.S. Customs Service, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Public Health Service, United States Attorneys, U.S. Court of Appeals, and United States Marshals Service. Information on National Archives Chinese materials is also available on-line.

Located in Seattle’s Volunteer Park, SAAM, which was the original building for the Seattle Art Museum, has collections in East and South Asian painting, sculpture, textiles and other media. Superb tours and educational materials are available to interested teachers. Occasional exhibits by Asian American artists.

The Wing Luke, named to honor the late Seattle City Councilman, is both museum and community center for the International District. “One Song, Many Voices: The Asian Pacific American Experience,” a permanent exhibit, surveys the history of Asian Pacific Islanders in the Northwest. WLAM also offers tours, outreach kits for classroom use, and discounted lunches at neighboring restaurants for interested tour groups.

Each of the documents in the curriculum material has a number that corresponds to the number listed here, for coordination with sources and organization by subject or theme. Under each section heading, a brief explanation accompanies the citation and index number. The documents are divided into six units, but teachers and students may organize them as they see fit. Click on any of the numbers below to go to a source document, or scroll through the text index.

A. Coming to America: Immigration

1. "An act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to Chinese" (approved May 6, 1882). The Statutes at Large of the United States of America from December, 1881 to March, 1883. Vol. XXII, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1883), p. 58-62.

2. Excerpts from "An act to limit the immigration of aliens into the United States…," more commonly called the Immigration Act of 1924 (approved May 26, 1924). The Statutes at Large of the United States of America from December, 1923 to March, 1925. Vol. XLII, Part 1, Chapter 190, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1925), p. 153-69.

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and the 1924 Immigration Act (or National Origins Act) are two of the most restrictive pieces of immigration legislation in United States history. The former targeted Chinese laborers, while the latter was designed to limit all but Northern European immigration to the United States. The entire text of the 1882 Act is provided here along with excerpts from the 1924 Act.

3. Instructional questions and answers for immigration officials: treaties, laws and rules governing the admission of Chinese, 1933, p. 7-12 (excerpts). Executive Files Retrieved from Immigration and Naturalization Service Including Instructions for Chinese Inspectors, compiled by M. C. Faris. National Archives and Records Administration: Pacific-Alaska Region (Seattle).

4. Instructional questions and answers for immigration officials: treaties, laws and rules governing the admission of Chinese, 1933. Warrants and Investigations, p. 33-44 (excerpts). National Archives: Pacific-Alaska Region (Seattle).

The various immigration laws necessitated the creation of a trained bureaucracy to implement them. As these two documents show, by 1933 government employees were taught the intricacies of the various laws pertaining to the Chinese through detailed question and answer sessions. The material also shows how immigration officials thought the Asians were circumventing the laws in order to obtain residency in the United States.

5. Census of Chinese students following the Immigration Act of 1924. Included with Instructional questions and answers for immigration officials: treaties, laws and rules governing the admission of Chinese, 1933. National Archives: Pacific-Alaska Region (Seattle).

One concern of immigration officials was the abuse of the laws which allowed foreigners to study in the United States. Here the underlying fear was that eligible Chinese were either not students at all or that they were not returning to China following their education. This document suggests that immigration officials kept a careful eye on these students.

6. "1900 Foreign Born Population by Country of Birth, by County." Census Reports. Twelfth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1900. Vol. 1, Part I, Population (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1901).

While immigration laws and the efforts of the white population tried to keep Asians out of Washington these efforts were never completely successful. The 1900 federal census documents both Chinese and Japanese enclaves located throughout the state, including the rural areas of eastern Washington.

7. In the matter of the application of Fong Wong for admission to the United States as a returning native born citizen, 1905-1909. Record Group 85, Box 80, File RS2706, Fong Wong. Immigration and Naturalization Service, Seattle District Office, Chinese Exclusion Act Case Files, c.1882-1920. National Archives and Records Administration: Pacific-Alaska Region (Seattle). (Documents: 7a, 7b, 7c, 7d, 7e, 7f, 7g, 7h)

8. In the matter of the application of Lin Doo for the determination of his merchant status prior to his departure for China, July 23, 1908. Record Group 85, Box 64, File RS2129, Lin Doo. National Archives: Pacific-Alaska Region (Seattle). (Documents: 8a, 8b, 8c, 8d)

Even though the 1882 act primarily excluded laborers, Chinese merchants as well as native born Chinese had to petition for permission to travel to and return from China. The process was a grueling one, as these documents illustrate.

9. Certificate verifying that Emma Kao Chong and her surviving children are exempt from the Chinese exclusion laws, April 22, 1909. Record Group 85, Box 64, File RS2144, Emma Kao Chong. National Archives: Pacific-Alaska Region (Seattle). (Documents: 9a, 9b)

10. In the matter of the application of Eng Sue for admission to the United States as a returning registered Chinese, May 11, 1909. Record Group 85, Box 64, File RS2133, Eng Sue. National Archives: Pacific-Alaska Region (Seattle). (Documents: 10a, 10b)

The Chinese who were permitted to reside in the United States had to prove, through photographs, passports, certificates of residence, or proof of birth in this country, that they were indeed who they claimed to be. Written proof had to be carried on the person at all times. If found without the proper certification of one's right to residency by a law enforcement officer or immigration official, one could face a deportation hearing. These documents illustrate two of the forms whereby residency could be assured.

11. Alien's Personal History and Statement: Minoru Fujita, May 9, 1942. Record Group 147, Box 14, Multnomah County Local 12. Selective Service System, Oregon State Headquarters, Portland, c.1942-1946. National Archives and Records Administration: Pacific-Alaska Region (Seattle).

(Documents: 11a, 11b, 11c, 11d)

12. Statement of United States Citizen of Japanese Ancestry (ruled "non acceptable" by the draft board): Jack Itomi Shiozaki, September 30, 1944. Record Group 147, Box 14, Multnomah County Local 9. National Archives: Pacific-Alaska Region (Seattle). (Documents: 12a, 12b, 12c, 12d)

13. Statement of United States Citizen of Japanese Ancestry (ruled "acceptable" by the draft board): Yoshito Iwamoto, May 11, 1944. Record Group 147, Box 14, Multnomah County Local 10. National Archives: Pacific-Alaska Region (Seattle). (Documents: 13a, 13b, 13c, 13d)

Regardless of their status as U.S. citizens, Selective Service files were compiled on Japanese men during World War II. As the surviving record shows in these three documents, the questions asked of the potential recruits yield a vast amount of immigration, family, and personal data ranging from schools attended to hobbies and favorite magazines.

14. "Interview: Hing W. Chinn," in Reflections of Seattle's Chinese Americans: The First 100 Years, Ron Chew, ed. (Seattle: Wing Luke Asian Museum and the University of Washington Press, 1994), p. 16.

In 1992, the Wing Luke Asian Museum in Seattle's International District conducted a series of interviews with older Chinese residents who lived or grew up in Seattle. These interviews became part of an exhibit on the changing features of Chinatown as well as a book on Chinese Americans in Seattle. Hing Chinn's interview illustrates what coming to America was like after the 1882 Exclusion Act. Immigrants were asked detailed questions about their residence in China, family connections in the United States, and motives for moving to America. Almost all immigrants to the Pacific coast passed through Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay. Angel Island was for Asian immigrants what Ellis Island, New York, was for European immigrants: a point of entry and exit to the United States. Quotas, quarantines against infectious diseases, and bureaucratic entanglements kept many immigrants waiting in processing centers for weeks, even months.

15. Selection from Carlos Bulosan, America is in the Heart: A Personal History (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1943, 1946), p. 99-103.

Carlos Bulosan, a noted Filipino American author and poet, came to the United States in 1930. He was seventeen years old. Encouraged by stories of wealth and opportunity in America, he traveled to find his brother, who had left the Philippines several years earlier, and his future. In the U.S., Bulosan found discrimination, harsh working conditions, and violence. But he also believed that America, his adopted home, could and should provide opportunity for all of its citizens. As Bulosan cultivated his talent as a writer, he became a labor organizer in California and the Pacific Northwest. His affiliation with organized labor and left-wing political causes earned him both contempt and admiration. This excerpt, taken from his autobiography, describes his arrival in the U.S.

B. A Hard Day's Work: Canning Salmon

Most of this section is taken from union records for the Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union, organized in Seattle on June 19, 1933 to represent workers in the agricultural industries and Northwest salmon canneries. Filipino Americans quickly became the leaders in this multiethnic labor union. The first president, Virgil Duyungan, chartered Local 18257 (later Local 7) with the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Duyungan was killed by an agent of a labor contractor in 1936; his successor, Harold Espe, successfully ended the contract system and gained a hiring hall for cannery workers in 1937. The hiring hall freed workers from depending on unscrupulous contractors for seasonal work. Conflict with the national AFL office over organizing the racially segregated locals led to conflict. The AFL called those who wanted a multiethnic union Communists. The CWFLU rank and file voted to affiliate with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) instead. These documents illustrate both the multiethnic character of the early CWFLU as well as conflicts between labor and management, between dueling labor organizers, and within the union itself. Other documents illustrate aspects of the Northwest's canned salmon industry.

Most of this section is taken from union records for the Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union, organized in Seattle on June 19, 1933 to represent workers in the agricultural industries and Northwest salmon canneries. Filipino Americans quickly became the leaders in this multiethnic labor union. The first president, Virgil Duyungan, chartered Local 18257 (later Local 7) with the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Duyungan was killed by an agent of a labor contractor in 1936; his successor, Harold Espe, successfully ended the contract system and gained a hiring hall for cannery workers in 1937. The hiring hall freed workers from depending on unscrupulous contractors for seasonal work. Conflict with the national AFL office over organizing the racially segregated locals led to conflict. The AFL called those who wanted a multiethnic union Communists. The CWFLU rank and file voted to affiliate with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) instead. These documents illustrate both the multiethnic character of the early CWFLU as well as conflicts between labor and management, between dueling labor organizers, and within the union itself. Other documents illustrate aspects of the Northwest's canned salmon industry.

16. Selection from Special Report on the Salmon Canning Industry in the State of Washington, and the Employment of Oriental Labor (Olympia: State Bureau of Labor, 1915), p 1, 11, 13, 15. Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries.

Despite immigration restrictions and violent riots, Asian laborers continued to work in Washington state industries. The fisheries employed many Chinese, but as the Chinese labor pool shrank in the early twentieth century, Japanese workers emerged to take their place. Anti-Japanese sentiment was at a high pitch in the 1910s. The recent success of the Japanese against the Russians in the Russo-Japanese War encouraged fear of an Asian threat to United States interests in the Pacific. And the 1907 Gentlemen's Agreement limited but did not stop immigration.

This 1915 report from the State Bureau of Labor characterizes Chinese workers as docile and loyal, but Japanese workers as dishonest and inefficient. What is curious about this document is how the authors make distinctions between Asian immigrant groups—all of which reinforce notions of white supremacy threatened by foreign migration. The selections from this report illustrates white stereotypes of Japanese and Chinese, and it provides a description of how the "Iron Chink" salmon cleaning machine worked.

17. Advertisement for the "Iron Chink," Pacific Fisherman, Vol. 5, no. 11 (November 1907), p. 30.

In 1903, Seattle entrepreneur and inventor E. A. Smith built a machine designed to replace Chinese butchers in salmon canneries. Smith's company sold this machine, the so-called "Iron Chink," by intentionally manipulating racist sentiment and economic concerns over dwindling labor supply. The 1882 Exclusion Act severely limited further Chinese immigration to the United States. White laborers, fearful of losing their jobs, threatened cannery operators who hired non-native labor. Proponents of the machine predicted that it would soon drive all Asian labor out of the canneries. This advertisement from Pacific Fisherman, the trade publication for the Pacific coast fisheries, extols the virtues of the "Iron Chink" by reminding readers of the perils of Chinese labor.

18. Photo of an "Iron Chink" cleaning machine in operation at the Pacific-American Cannery, Fairhaven, Washington, c. 1905. Special Collections, University of Washington, Social Issues File #Cb, UW Negative #9422.

Smith Manufacturing Company, maker of the so-called "Iron Chink," and fisheries boosters proclaimed that mechanization would eliminate the need for Asian labor. But the photograph provided here, taken at the Pacific-American Cannery in Fairhaven, near Bellingham, tells a different story. While Chinese labor declined in the early twentieth century, other groups came to take their place. In this photograph, a Chinese butcher loads salmon onto the machine for processing.

19. Untitled poem by Trinidad Rojo, from Alaskeros: A Documentary Exhibit on Pioneer Filipino Cannery Workers, 1988 (Exhibit interviews). Project director and photographer, John Stamets; text by Peter Bacho. Seattle: IBU/ILWU, Region 37. (Tape: BB-118). Courtesy of the Museum of History and Industry, transcribed by Bing Ardanas.

Poems were a common form of personal expression and political protest for many Asian Americans. Trinidad Rojo, a Filipino labor organizer and author, penned this poem while working as an Alaskero. It is translated from the original, written in Ilocano, a language native to the Philippines. Rojo, who served as president of the Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union in the 1960s, used verse in the struggle to improve working conditions.

20. Election Ballot, CWFLU, Local 7 (n.d., 1935?), Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union, Local 7 Records, Accession No. 3927. Special Collections, University of Washington.

A ballot for Local officer elections.

21. Petition to E. Pat Kelly, director, Department of Labor and Industries, State of Washington July 23, 1934. Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union, Local 7 Records, Accession No. 3927. Special Collections, University of Washington. (Documents: 21a, 21b)

A petition asking for state action against the Frye Lettuce Farm at Monroe for unsafe working conditions.

22. Internal memo, showing committees elected along ethnic lines (April 2, 1936). Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union, Local 7 Records, Accession No. 3927. Special Collections, University of Washington.

The AFL organized its unions along racial lines. This memo shows how the CWFLU internal committees were divided by race and ethnicity.

23. Referendum Ballot on AFL or CIO affiliation (c. 1937). Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union, Local 7 Records, Accession No. 3927. Special Collections, University of Washington.

In 1937, the CWFLU held its first election for affiliation with the AFL or the CIO, which organized industrial, not trade, workers.

24. Informational pamphlet, United Cannery Agricultural Packing and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), CIO-affiliated union (c. 1937). Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union, Local 7 Records, Accession No. 3927. Special Collections, University of Washington. (Documents: 24a, 24b, 24c)

This pamphlet, distributed by UCAPAWA organizers, urged CWFLU workers to choose the CIO. It also mentions the Wagner Labor Act, a New Deal law that encouraged union expansion and activism.

25. Petition from New England Fish Company cannery at Noyes Island, Alaska, to CWFLU headquarters in Seattle July 21, 1938. Cannery Workers' and Farm Laborers' Union, Local 7 Records, Accession No. 3927. Special Collections, University of Washington.

A petition demanding union action against Dick Kanaya, foreman at the New England Fish Company cannery in Noyes Island, Alaska.

C. Violence and Reaction: Chinese Exclusion and Responses to Racism

26. "Letter from Watson Squire, Washington Territorial Governor, to L.Q.C. Lamar, Secretary of the Interior, October 21, 1885," from Report of the Governor of Washington Territory to the Secretary of the Interior, 1886 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1886), p. 866. Special Collections, University of Washington.

27. "Letter from Watson Squire, Washington Territorial Governor, to F. A. Bee, Chinese Consul, San Francisco, October 21, 1885," from Report of the Governor of Washington Territory to the Secretary of the Interior, 1886 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1886), p. 870. Special Collections, University of Washington.

28. "Letter from John Arthur to Watson Squire, Washington Territorial Governor, November 4, 1885," from Report of the Governor of Washington Territory to the Secretary of the Interior, 1886 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1886), p. 875. Special Collections, University of Washington.

After the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, anti-Chinese sentiment throughout the American West reached a climax. Fearful of Chinese laborers taking their jobs, white workers in Tacoma, affiliated with the Knights of Labor and local vigilante groups, organized to drive the Chinese out. Meanwhile, on a hop farm in Squak Valley, now present-day Issaquah, a group of whites torched the shanties of Chinese workers, killing three. Events quickly overtook territorial authorities as white Tacomans forced nearly 700 Chinese from their homes. The next year, on February 8, a similar episode erupted in Seattle. The following letters relate to the Tacoma incident and the event that preceded it, the killing of several Chinese near present-day Issaquah.

29. Letter to Thomas Burke, May 1, 1890. Thomas Burke Papers, 1785-1925. Manuscripts and University Archives, University of Washington Libraries.

30. Letter to Thomas Burke, May 17, 1920. Thomas Burke Papers, 1785-1925. Manuscripts and University Archives, University of Washington Libraries.

31. Letter to Thomas Burke, September 27, 1920. Thomas Burke Papers, 1785-1925. Manuscripts and University Archives, University of Washington Libraries.

Despite language difficulties, cultural barriers, and racial discrimination, many Asian immigrants established close ties with their white neighbors in Washington state. These four letters, taken from Thomas Burke's papers, illustrate how whites and Asians transacted business and maintained friendships. Burke, a prominent businessman, lobbied for Seattle to increase its trade with East Asia. One friend and occasional partner was a powerful Chinese merchant and labor contractor. His letter asks Burke to use his influence to promote steamship lines between China and Seattle. Another Burke associate made his fortune in labor and merchandise as well and returned to China in the 1920s to build railroads. He wrote to Burke often, asking for business advice and help with raising capital.

D. Executive Order 9066: The Japanese/Japanese American Internment

32. Civilian Exclusion Order No. 79, issued by J. L. DeWitt, Lieutenant General U.S. Army, 1942. Photograph of original poster, Special Collections, University of Washington, Social Issues File #Cc/i.

33. Evacuation "instructions to all persons of Japanese Ancestry," also issued by DeWitt in 1942. Photograph of original poster, Special Collections, University of Washington, Social Issues File #Cc/i.

The two orders issued by Lieutenant General J. L. DeWitt, were posted throughout Japanese

American neighborhoods immediately after President Franklin D. Roosevelt's executive order.

34. Map of "Alien Exclusion Areas." Reprinted with permission, Seattle Post-Intelligencer (March 23, 1942).

35. Map of "Army Watching Japs on Bainbridge Island." Reprinted with permission, Seattle Post-Intelligencer (March 25, 1942).

These two maps from the Post-Intelligencer show the exclusion areas in Washington state and along the Pacific Coast, excluding Hawai'i.

36. Photo of Japanese American woman and baby, Bainbridge Island, 1942. Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection (PI-28050, 3/30/42), Museum of History and Industry, Seattle.

This photograph of a mother and child was taken by a Post-Intelligencer photographer during the evacuation of Bainbridge Island, which once had one of Washington state's largest Japanese American farming communities.

37. Two photos of the Minidoka Consumers' Cooperative taken c. 1943 for the Minidoka Interlude. Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Social Issues File #Cciii.

These photos were taken at Camp Minidoka, Idaho, where most Washington State internees lived during World War II. Both were part of a book on the camp which was written by the Japanese internees and published by the United States War Relocation Center. (The microfilmed publication is located—as A7797—at the University of Washington Suzzallo Library.) These photographs of the Minidoka Consumers' Cooperative document how some of the residents' basic economic needs were attended to, and how Japanese Americans creatively responded to the difficult life of incarceration.

38. Pacific Citizen, September 3, 1942, front page. Wing Luke Asian Museum Archives, Seattle.

A front-page article from the Pacific Citizen, the newspaper of the Utah chapter of the Japanese American Citizens' League (JACL), details what Minidoka was like when it opened in late 1942.

39. Minidoka Irrigator (May 19, 1945). Wing Luke Asian Museum Archives, Seattle.

Issues of the Minidoka Irrigator, a newspaper published under supervision by Japanese Americans in the internment camp, are windows into the daily activities of the internees from sports events and social activities to events related to the war. The excerpts taken from this 1945 issue portray a camp in transition as the Japanese were allowed to return to their Pacific Northwest homes, or to localities elsewhere in the United States, and the reactions of white Americans as the war nears its end.

40. Program, "Concert by the Minidoka Mass Choir," 1943. Wing Luke Asian Museum Archives, Seattle.

A program from a choral concert at Minidoka shows how entertainment blended patriotism and popular American culture.

41. Petition, c. 1944, by internees at Minidoka to the WRA. Wing Luke Asian Museum Archives, Seattle.

A draft of a petition from Minidoka internees to the War Relocation Authority (WRA) requesting equal rights when enlisting for the armed services.

42. Statistics on internment and postwar resettlement, in WRA: A Story of Human Conservation (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946), p. 196-212.

Statistics from the WRA's final report convey the scale of the evacuation and resettlement of Japanese and Japanese American internees.

E. Building Community: Political Activism and Social Concerns

43a. "Filipino Tragedy Continues (editorial)," The Philippine Review (Seattle, Washington), Vol.1, no. 10 (February 1931), p. 8. Special Collections, University of Washington.

In this editorial, the editors call for collective action to prevent violent attacks on Filipinos along the West Coast.

43b. Amado D. Dino, "The Filipino Situation in America (editorial)," The Philippine Review (Seattle), Vol.1, no. 10 (February 1931), p. 8. Special Collections, University of Washington.

Dino takes a slightly different position from the above editorial, arguing that continued Filipino immigration to the United States is the cause of racial violence.

44. "A Call to Organize Nationally (editorial)," from Filipino Forum (Seattle) Vol. 40, no. 8 (August 1968), p. 2. Special Collections, University of Washington.

45. "Not Yet, Victorio, Not Yet" (poem), from Filipino Forum, Vol. 40, no. 8 (August 1968), p. 2. Special Collections, University of Washington.

The editorial and poem, taken from the Filipino Forum, illustrate the continuing call for an organized, unified Filipino American community. Both items were printed in memory of Victorio A. Velasco, Forum publisher, poet, community activist and labor organizer. Velasco was killed on July 13, 1968, by a gas tank explosion in a Salmon cannery bunkhouse in Waterfall, Alaska, with three other Filipino workers. The Forum, one of many Asian American community newspapers throughout the Pacific Northwest, served both as a voice for political action as well as an arena for political debate.

46. Campaign brochure for Wing Luke for City Council. Wing Luke Asian Museum Archives, Seattle.

Wing Luke, a Seattle native, was the first Asian American elected to the Seattle City Council and one of most prominent Asian American politicians of his time. A graduate of the University of Washington, Luke served in the U.S. Army during World War II, earning a Bronze Star. During his meteoric career, Luke became a prominent Seattle attorney, was appointed Assistant Attorney General, and was active in many civic groups. In 1960, he was elected to the Seattle City Council, where he became an advocate for civil rights and sanitation reform. In 1965, he died in an airplane crash while touring eastern Washington. The Wing Luke Asian Museum in Seattle's International District was named in his honor.

Luke was the first of several Asian Americans to serve in local and statewide politics. The two documents below illustrate his stature and importance as a leader in Washington's Chinese American community. The campaign brochure details his many accomplishments during his bid for the Seattle City Council.

47. "Remarks," meeting to discuss Chinese American political action, August 17, 1960. Wing Luke Asian Museum Archives, Seattle.

This document is from an informal meeting of Seattle Chinese Americans to discuss forming a political action group. No formal action was taken after this meeting, but Luke's remarks point to the growing political clout of Asian Americans in Washington state.

48. Information Pamphlet, DPAA Services, c. 1972. Demonstration Project for Asian Americans Records, 1970-1981. Manuscripts and University Archives, University of Washington Libraries.

Asian immigration to Washington state increased dramatically after the passage of the 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act. The sudden influx of immigrants coupled with already strained social services designed for current residents threatened many Asian American communities, especially those located in urban areas. In 1969, Asian American Social Workers (AASW), a national organization, started the Demonstration Project for Asian Americans. This agency, funded largely by federal grants, labored to improve health and housing services while acting as a clearing house for community activism. This 1972 pamphlet from the Seattle DPAA branch illustrates how the definition of Asian American expanded by the early 1970s. It also illustrates how Asians, stereotypically cast as passive and quiet, often struggled vocally and aggressively for their civil rights.

49. "Interview: Anne Chinn Wing," in Reflections of Seattle's Chinese Americans: The First 100 Years, Ron Chew, ed. (Seattle: Wing Luke Asian Museum and the University of Washington Press, 1994), p. 10.

Generational identity is an important part of Chinese and Chinese American culture; and filial piety, reverence for one's ancestors and parents, is an important component of many Asian American communities. But as this interview suggests, older Chinese Americans view the younger generation, who are seen as more fully American than Chinese, with mixed feelings.

F. Counting and Measuring: Immigration Statistics

The following charts and maps, adopted from various U.S. census reports, illustrate the changing immigration and residence patterns of Asian Americans in Washington state and the Pacific Northwest. The first set of charts and maps, compiled by Calvin Schmid, former state census registrar, show the changing demographics of Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos from 1900 to 1960. Schmid tracks residence, population, occupation, education, age and sex differences for all three groups. (Note: Schmid uses racial labels and categories appropriate to the 1960s. Teachers may want to point this out to their students.)

A second set of maps and statistics is taken from an atlas based on the 1990 U.S. Census. The maps illustrate how Asian Americans are a significant presence nationwide and especially in the Pacific Northwest. The third set, taken from the 1980 U.S. Census, includes residence maps of Seattle and a line graph of population change from 1860 to 1980. Issued by the Washington State Commission on Asian Affairs, these charts were part of a public report calling for greater attention to Asian American and Pacific Islander social needs. The Commission, established in 1967, continues to serve as an important policy organization for the state's Asian Americans. Finally, a chart of selected social and economic characteristics of the national Asian population from the 1990 census allows students to see the type of data used to produce the maps and charts in this unit.

50. "Trends in Nonwhite Racial Groups, Washington: 1870-1960," from Calvin Fisher Schmid, Nonwhite Races, State of Washington (Olympia: Washington State Planning and Community Affairs, 1968), p. 18.

51. "Trends in Nonwhite Racial Groups, Seattle: 1900-1960," from Schmid, p. 50.

52. "Trends in Nonwhite Racial Groups, Spokane: 1900-1960," from Schmid, p. 51.

53. "Trends in Nonwhite Racial Groups, Tacoma: 1900-1960," from Schmid, p. 52.

54. "Trends in Rural-Urban Distribution of Racial Groups, Washington: 1910-1960," from Schmid, p. 24.

55. "Distribution of Japanese by Economic Area: Washington, 1900 and 1920," from Schmid, p. 33.

56. "Distribution of Japanese by Economic Area: Washington, 1940 and 1960," from Schmid, p. 34.

57. "Japanese Population by Counties, Washington: 1900-1960," from Schmid, p. 35.

58. "Japanese Population, Washington: 1960," from Schmid, p. 36.

59. "Distribution of Chinese by Economic Area, Washington: 1900 and 1920," from Schmid, p. 37.

60. "Distribution of Chinese by Economic Area: Washington, 1940 and 1960," from Schmid, p. 39.

61. "Distribution of Filipinos by Economic Area: Washington, 1960," from Schmid, p. 42.

62. "Japanese Population, Seattle: 1920," from Schmid, p. 63.

63. "Japanese Population, Seattle: 1960," from Schmid, p. 64.

64. "Chinese Population, Seattle: 1920," from Schmid, p. 65.

65. "Chinese Population, Seattle: 1960," from Schmid, p. 66.

66. "Filipino Population, Seattle: 1960," from Schmid, p. 67.

67. "Japanese Population, Spokane: 1960," from Schmid, p. 71.

68. "Japanese Population, Tacoma: 1960," from Schmid, p. 75.

69. "Age and Sex Characteristics, Japanese (1910, 1940, 1960)/Chinese (1910, 1940, 1960)/Filipino (1940, 1960): Washington," from Schmid, p. 85-87.

70. "Trends in Marital Status, Racial Groups, Washington: 1900 to 1960," from Schmid, p. 103.

71. "Trends in Educational Status: College Graduates, Nonwhite Racial Groups, Washington: 1940-1960," from Schmid, p. 115.

72. "Trends in Educational Status: Median School Year Completed, Nonwhite Racial Groups, Washington: 1940-1960," from Schmid, p. 116.

73. "Trends in Educational Status: High School Graduates, Nonwhite Racial Groups, Washington: 1940-1960," from Schmid, p. 117.

74. "Trends in Occupational Status: Male Labor Force, Nonwhite Racial Groups, Washington: 1940-1960," from Schmid, p. 122.

75. "Trends in Occupational Status: Male Labor Force, Nonwhite Racial Groups, Washington: 1940-1960," from Schmid, p. 123.

76. "Trends in Occupational Status: Male Labor Force, Nonwhite Racial Groups, Washington: 1940-1960," from Schmid, p. 124.

77. "Asian American Population, Northwest," in Mark T. Mattson, Atlas of the 1990 Census (New York: Macmillan, 1992), p. 123.

78. "Asian American Population [U.S.]," in Mattson, p. 116-17.

79. "Selected Social and Economic Characteristics for the Asian Population, 1990," in We the American . . . Asians (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of the Census, 1993), p. 8-9.

80. "Asians in the United States," from Commission of Asian Affairs, Countdown: A Demographic Profile of Asian and Pacific Islanders in Washington State (Seattle: The Commission, 1982), p. 17.

81. "Asians in Washington," from Countdown, p. 18.

82. "Asians by Census Tract — Distribution of Seattle Asians, 1980," from Countdown, p. 21.

83. "Distribution of Seattle Japanese, 1980," from Countdown, p. 22.

84. "Distribution of Seattle Filipino, 1980," from Countdown, p. 23.

85. "Distribution of Seattle Chinese, 1980," from Countdown, p. 24.