By Owen Oliver

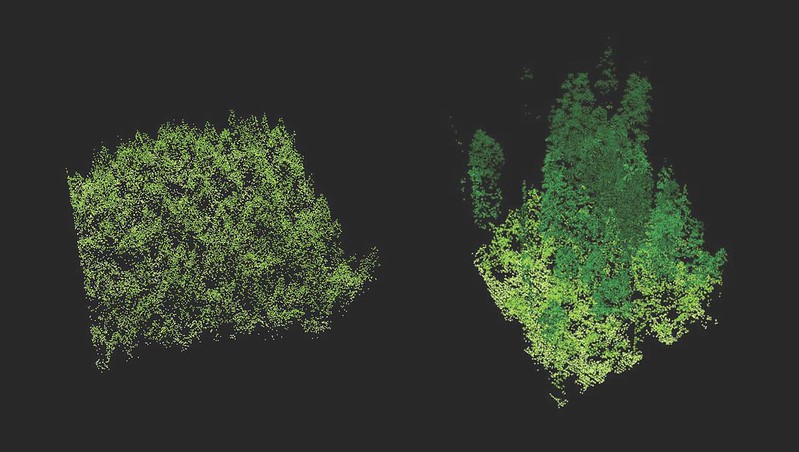

After a short eventful paddle, we were back into the office of HIA (Hoonah Indian Association). We were greeted by Ian Johnson who currently serves as the Hoonah Indian Association Environmental Coordinator for the Hoonah Native Forest Partnership while also being the Community Catalyst. Ian is from Minnesota, however he completed his undergraduate biology degree in Wisconsin. Recently he graduated with a master’s in Wildlife Biology and Conservation from the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He brings his studies and experiences to the Hoonah Native Forest Partnership and contributes to their mission of “achieving a measurable and resilient blend of timber, salmon and deer production, local economic diversification and improved watershed health” (Sustainable Southeast) with the ultimate goal of putting the tribe front and center in the co-management of natural resources on Chichagof Island such that resource management is sustainable (from a an ecological and economic standpoint), and meets the cultural and practical needs of the tribe. Next to Ian was Sean Williams who is from Louisiana State University and brought into Hoonah by the AmeriCorps VISTA program. Sean is focusing his masters degree on Environmental Sciences and he brings unique skills to Hoonah. Sean’s focuses in Hoonah include projects within Port Frederick and working with the youth outdoors. Ian who is interested in GIS/Aerial photography begins the presentation informing us about new technologies they are using in Hoonah. LIDAR or light imaging, detection, and ranging is currently being used to understand efficient and sustainable subsistence practices. LIDAR works by sending wavelengths from a plane down towards the ground and measuring the wavelengths that are reflected back. The data is collected and through programs you can create 3-D topographic maps. LIDAR can even determine where certain berry patches are and how the yield changes from each patch. This could be useful in many ways, as subsistence practices can become more resourceful and efficient, but they can also monitor from the sky where you used to have to hire a crew, which turns out to be more expensive. Nevertheless, the Hoonah Native Forest Partnership provides training and jobs to HIA members who work on the ground to check and monitor resources assessed from the sky.

Figure 1 (Sarah Frey) – LIDAR technology to map out old growth forests (right). On the left is new growth

Figure 2 (Hoonah Native Forest Project Area) – they hope to use LIDAR around the city of Hoonah and important streams and game trails

Once the presentation was done we all climbed into a small touring bus driven by our tour guide Zach to check out HNFP’s work on tree thinning and salmon stream restoration just outside of Hoonah. We jumped out and Ian (Figure 3, in the green) immediately was excited to tell us about their studies on “natural” tree thinning in the area. Thinning is a practice to remove some trees in immature areas to reduce competition, and eventually increase growth of the remaining trees (a process that happens naturally, but which can be sped up by people). The main reason why HNFP is practicing thinning is to redistribute the trees so that older trees will be able to survive which promotes higher quality timber. Figure 4 shows natural thinning in action. See how the bark is cut and the wood is exposed.

Figure 4 (Tim Billo) Girdling the less healthy trees causes them to die and fall to the ground, thus releasing the healthy trees from competition, promoting the growth of new merchantable timber more quickly, as well as better wildlife habitat. Deer don’t like dense stands. While you could just saw the trees down, sawing the trees down leaves the forest floor looking like a giant game of “pick up sticks” which no one, including deer, wants to clamber over. Natural thinning is cheaper and treefall to happen more gradually. It also creates snags which are good for other kinds of wildlife.

While Ian was excited to show off their work on thinning, I sensed that their prized work was their restoration of a nearby salmon stream. We walked a bit further along the small gravel road and dropped along the stream bed. There were many comments about the state of the salmon stream bed, most of them were about the lack of water. When I mean lack of water, I mean no water, the stream was completely dry. Sean said “Hoonah had only 4 days of rain this whole summer. This is very weird and unusual, it’s usually raining the whole summer.” While a dry stream is boring with the lack of salmon trying to complete their journey, it brings a different perspective. We were able to walk right in middle of the stream and have the ability to get down low and pretend to be a salmon, imagining how they would navigate through the obstacles that have been placed and built upon. As a Fishery Sciences student I got quite a kick out of this. Ian explains how he has worked with his peers to restore this particular salmon stream. The most important element of a healthy stream is having dead wood in the streams. Figure 5 shows Ian explaining to us how you only need to place one dead log across the stream and more sticks and trees limbs will pile up. This is crucially important for the salmon because it helps control flow, creates shade, and builds up gravel for the salmon to use as spawning beds while laying their eggs. We learned about the types of salmon that use this particular stream the pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) and the dog salmon (Oncorhynchus keta). These salmon species are different in sizes and you can tell that these salmon used to be present in this stream. Ian brought us over and showed us various sized rocks. The smaller fish like the pink salmon prefer the smaller rocks when creating their spawning site and the bigger dog salmon prefer the much larger rocks. Once he told us this we were able to see the distinct piles of similar sized rocks laying around everywhere. Ian did a great job on informing us about the HNFP and their goal to restore salmon streams around Hoonah.

We climbed back onto the bus and drove back to Hoonah, but before we got back we stopped to explore the muskeg around Hoonah. Muskegs are the same as bogs, just worded differently in Alaska. Muskegs are super cool because of their acidic soil due to plants decomposing into peat and humus. Since muskegs are super acidic only certain plant species have adapted to these regions, the most notable is Sphagnum moss which can hold 40x its own weight in water. The coolest plant we found were Sundews (Droseraceae, Drosera). These carnivorous plants use sticky substances on their leafed surfaces to catch and lure insects (Figure 8). The acidity of bogs means that nutrients are leached out of the system, hence Drosera obtains nutrients from insects. In some cases, the water is so acidic that plants prefer not to use it–this is arguably true of Labrador tea, another common muskeg plant, which is drought adapted, through its leathery leaves with dense hairs on the undersurface.

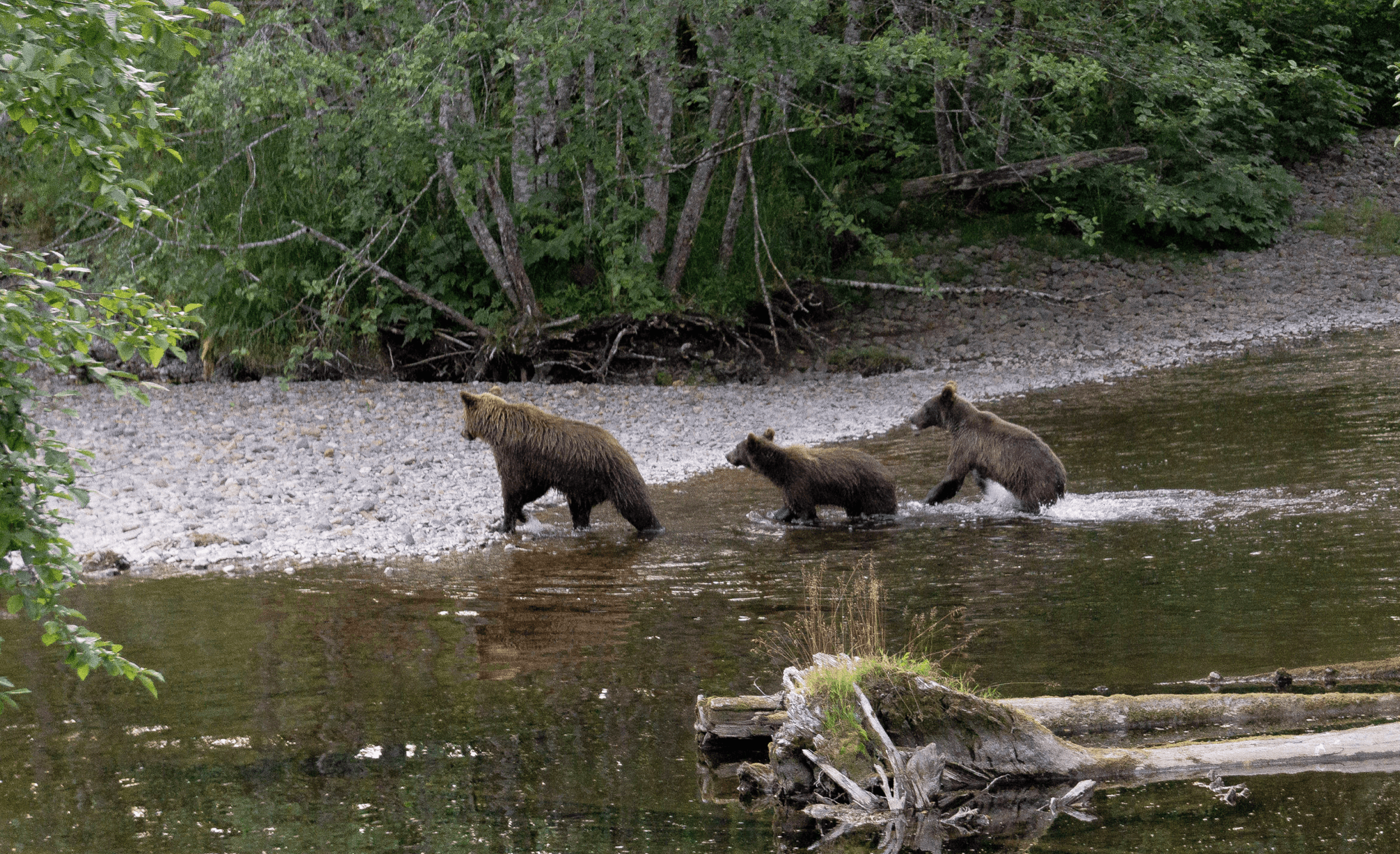

We ended the night with good food from a local Hoonah restaurant, The Fisherman’s Daughter, featuring local seafood, then embarked on a mission to see bears with Ian and Sean. We were told there are four grizzly bears for every person in Hoonah, so we all were pretty positive we were going to see some. As we arrived and parked just beyond the bridge, excitement grew and people were wondering when they were going to see their first grizzly bear. The day grew long, and the sun was setting, it had been 2 hours since we’d arrived and only saw salmon swimming up the stream. People were getting antsy and tired. However, the sounds of rustling in the salmonberry bushes got everyone right up. Finally, we saw a mother grizzly (coastal brown bear) and her two cubs (Figure 9). Everyone that night had dreams of seeing more bears. The journey wasn’t over yet.

Figure 9 (Owen Oliver)

Hoonah was just a short stop in our trip, but it was just as meaningful as the rest. Each person we met, each story we heard, each story we told, and each memory we created all came together to build a sense of place in Hoonah. Once the trip ended we looked back at our time in Hoonah and all acknowledged that the trip wouldn’t have been as great if we didn’t go to Hoonah first. In Hoonah we learned about Glacier Bay from the perspective of the people that had been there for centuries before the National Parks Service and other settlers. We traveled in their canoes while hearing their songs, the same songs that could have been sung while leaving and crossing Icy Strait. It’s pretty powerful to feel welcomed into a community that has had so many issues yet still hold on to such a rich history. We learned so much in the few days we were there that it’s hard to grasp everything. I know that I’ll be back in Hoonah once again.

Owen Oliver

Sources Cited