December 6, 2016

Sustainable Transportation Lab visits the White House

Don MacKenzie

Last week, I was honored to attend a roundtable convened by the White House to address the topic of vehicle automation and how it may affect future energy and environmental outcomes. Participants included officials from the Department of Transportation, Department of Energy, the EPA, and the Executive Office of the President, as well as representatives from industry, academia, and the non-profit sector.

The purpose of the roundtable was to solicit input for federal policymakers, to help inform the design of policies that can leverage vehicle automation to help reduce energy consumption and the associated environmental impacts of vehicles. In light of the uncertainty over how much emphasis the incoming Trump Administration will place on energy conservation, there was also a lot of discussion about the potential roles of state and local governments in achieving these goals.

I argued at the roundtable that we should not assume that the energy savings potential of automation will necessarily be achieved absent further policy actions. The biggest opportunity for saving energy is to increase occupancy factors, either through travelers sharing rides more often, or riding in smaller vehicles more often. It is widely thought that these changes will be more feasible if self-driving cars lead to increased use of on-demand mobility services. (The underlying assumption being that more people would use an Uber-like service if they didn’t have to pay for the driver.) This seems plausible when you look at the popularity of the ride-sharing services Uber Pool and Lyft Line in some markets, particularly San Francisco. But, it’s important to note that self-driving cars will dramatically reduce the principal incentive to share: cost savings.

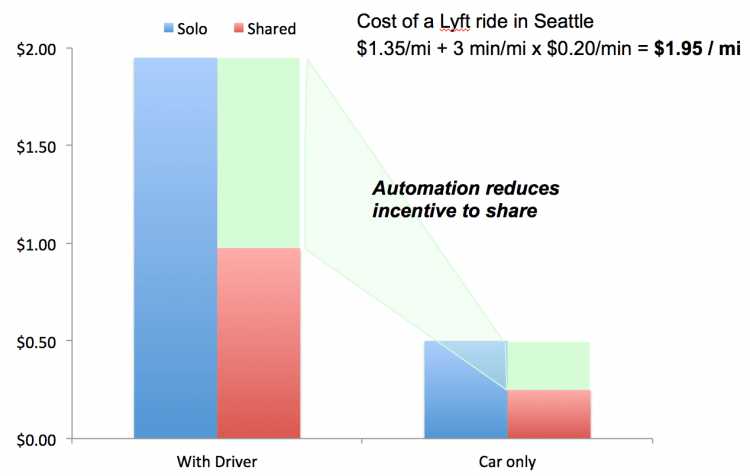

As shown in the following figure, the cost of a Lyft ride in Seattle is around $2.00 per mile (including both distance and time charges). Sharing a ride might cut this in half, saving each traveler $1.00 per mile. The total cost of a Lyft ride today includes both the cost of the driver and the cost of the vehicle, but with a self-driving car would include only the cost of the vehicle. The total cost of ownership for a new Prius is about $0.40 per mile over the first 5 years. Let’s round up to $0.50 per mile to account for higher vehicle costs due to sensors and computing power in a self-driving car. Now, the cost of getting your own ride is just $0.50 per mile, and the savings from sharing is just $0.25 per mile. In other words, the financial benefit of sharing a ride is greatly diminished. On top of that, consider the perceived safety of getting into a car with a stranger, without a company-vetted driver also being present. Given the greatly diminished incentive to share, I argued that we should not assume that ride-sharing will follow naturally from greater adoption of on-demand mobility, especially in self-driving vehicles. State and local policymakers can, however, increase the incentives to share rides by introducing road and congestion pricing, something that automation will make even more straightforward technically than it already is.

Fortunately, energy savings can still be achieved even if shared rides do not become more common. Instead of increasing the average number of passengers per seat, we could reduce the number of seats in each vehicle. Specialized one-person or two-person vehicles would consume much less energy per passenger mile – perhaps half as much as the typical car today. However, their success in the market may depend on federal regulators refraining from erecting additional barriers to their adoption. State and local policymakers can also help by integrating such vehicles as a first and last mile solution for mass transit.

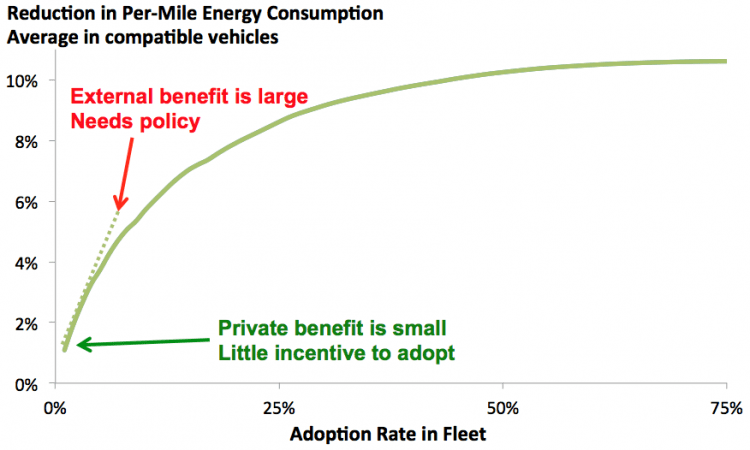

Finally, there was some discussion about whether EPA should offer credits (toward compliance with their automotive greenhouse gas emissions standards) to vehicles with energy-saving automation features. Generally, EPA requires data demonstrating real-world impact before granting such “off-cycle” credits. However, I pointed out that some technologies, like platooning, will offer greater energy savings when more vehicles on the road are mutually compatible. Below is a graph based on a rough analysis that I did. When there are few platooning-capable vehicles on the road, the energy savings are small, so there is little incentive for consumers to adopt the technology. However, as more and more compatible vehicles are on the road, the energy savings for all compatible vehicles increase. In this case, policymakers might be justified in offering incentives to early adopters of platooning technology, in order to “prime the pump” and help the market grow.

Recent Comments