The 2020 Preservation Week from April 26 to May 2 celebrates “Preserving Oral History.” Why do we preserve oral history? What uses do we have of these recordings and qualitative data? If you are a faculty member teaching a class that involves research, writing, or the examination of narratives and dominant discourse, you might consider incorporating primary source materials such as the oral histories housed in the UW Libraries Digital Collections for assignments, class activities, and research projects.

The Preservation Week programming also provides many valuable resources for the technical aspects of caring for collection materials long term. In the case of a born-digital collection like the UW Tacoma Oral History: Founding Stories, I might, for example, be concerned about choosing digital formats that can be read far into the future, data storage locations, and metadata that describes the content and its origin even if things get separated from the original context. I see preservation referring to primarily the technical considerations—often behind the scenes—that go into the work to ensure the long-term access and stewardship of records. We may want to preserve a memory or a moment in time, capturing it with oral history recordings or by archiving social media activities. But we are not preserving our cultural heritage for it to stay static. Rather, we want to continuously sustain and transform our culture and humanity as we interrogate and understand the past and respond to emergent social and environmental challenges of our time.

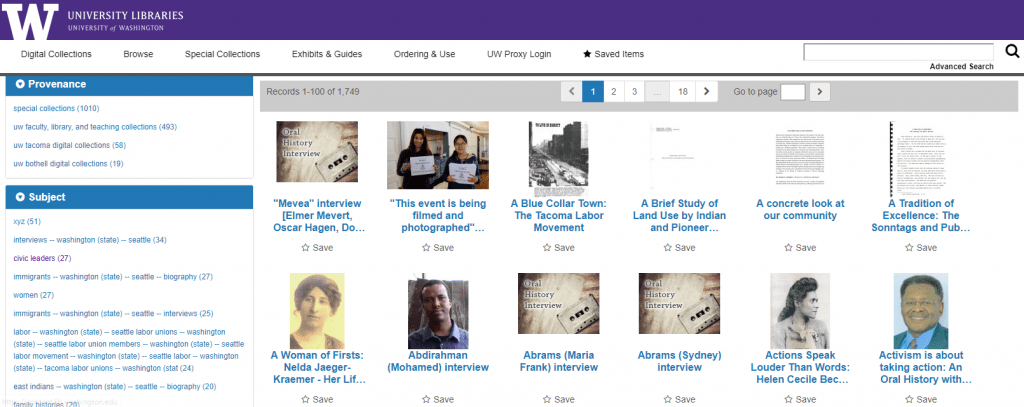

The oral histories archived in UW Libraries Digital Collections are likewise meant to be used and not simply preserved and stored away. Fortunately, the collection materials are open to all researchers, and the Digital Collections are accessible remotely.

This means they make great teaching materials even while we practice social distancing. Researchers and students can still access a large volume of primary sources without visiting the archives or picking up physical books. This is true for materials in UW Libraries Digital Collections and many other similar collections at other universities (unlike other university library collections, you typically do not need to be affiliated with the university to access their special collections). But to honor Preservation Week’s theme on oral history, I want to focus on oral history and offer a few ideas on how to teach with oral history digital collections.

Primary source research

Learning to navigate the oral history collections in the UW Libraries Digital Collections can be an fascinating and effective gateway to learning primary source research. The growing digital collections also require scholars to have a set of research skills that can be relevant to database search, digital literacy, and historical research.

For example, in an academic writing course that involves working with a variety of sources, have an activity for students to browse a collection, select two different oral histories, discuss how the narrators’ personal backgrounds and identities shape their perspectives, and reflect on the research experience. Or, as an alternative to a writing assignment, students may learn to use the primary sources as “raw data” to collaboratively create a Story Map; reflect on the spatial context of a particular group of narrators and how that shapes relationships, privilege, and oppression.

If your class assignment or project currently includes a research component, consider incorporating a virtual visit to the UW Libraries Digital Collections in your class. The lessons are valuable to include as part of a research assignment involving inquiry construction and thesis development. Admittedly, navigating the site may take some practice. So, here’s a reminder that libraries are not only collections but people: feel free to make an appointment with me or get help from librarians!

Study the local community and underrepresented voices

Oral history’s community-driven roots and conversational format illuminate diverse perspectives and some of the more recent memories. Its multiplicity and rawness mean the scale measuring historical significance is re-balanced; without the focus on a single narrative or expert, everyday and firsthand accounts are elevated. Therefore, it lends itself particularly well to subject areas like cultural studies and community-specific topics. The two main Tacoma oral history collections—the Tacoma Community History Project and the developing Founding Stories project, with interviews conducted as recently as 2020—contain fresh perspectives on neighborhood and urban history, economic development in the region, community outreach and relationships, as well as labor history and activism. Students and researchers can access oral history materials in full to form or supplement their research and analysis in disciplines like political science; urban studies; history; ethnic, gender, and labor studies; and other areas. A class can also view or listen to recordings and discuss them.

Close reading and textual analysis

The oral history collections mentioned here have complete transcripts. That means they are a valuable textual resource as much as they are multimedia. And because of the lengthy and conversational style, the oral history transcripts offer an insightful resource for teaching close reading. The exercise might surface themes, subjects, word choice, and patterns. As the narrators represent a personal point of view and may not always be factually accurate, analyses of the oral history transcripts may include valuable lessons on critical thinking and understanding of complex social contexts.

Interview projects

There are already examples of courses at UW Tacoma that include oral history interview projects as assignments. For reference, take a look at the class guide we put together for the spring 2020 course IAS 515/THIST 437 Doing Community History or the one my colleague Erika Bailey created earlier for TLAX 333 Latino Histories. And feel free to contact me, Joan Hua, if you would like more information or to discuss your ideas!