(Source: Morrison, Matthew. Pinterest. “Innocent People Killed by Police”.2020.)

The thing about the recent Black Lives Matter protests, is that this isn’t just about the recent death of George Floyd, or even just the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. This is bigger than that. World systems thinking prompts us to consider the pieces of the puzzle surrounding the murders of innocent black Americans. Black lives have been oppressed the entire duration of their time in this country, and were enslaved for most of the last three and a half centuries, and even now they are treated only a modicum better than they historically had been. The Black Lives Matter movement is about how historically banks wouldn’t lend to Blacks, and they couldn’t own homes in certain areas, and even now, a young Black boy walking home with Skittles is an offense punishable by death. THAT is why we rally, not because one more person died at the hands of police brutality in this country. Like systems theory, racism is not a collection of separate events, but rather a sum of its history.

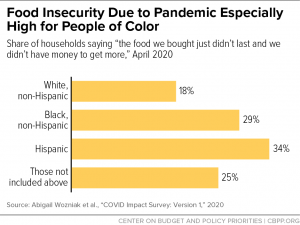

Right now, at this point in history, we are at a potential boiling point, where we have the proper amount of anger and people with time on their hands to make this a pivotal point in our political state, and in history. People are home, due to the coronavirus pandemic, and on their phones all day, seeing the police take innocent Black lives, except this time, we have an evil president who citizens are already upset with for dropping the ball on the pandemic response team, and properly handling the coronavirus pandemic so that the lives lost to Coronavirus can also start declining. With the anger towards Trump, and the attention to what is happening in the nation, made easier by the technological age, we are uniting for a common cause, and are not backing down, even a week after George Floyd’s death. With all of this anger, at the exact time, and with the exact circumstances we had, we are also seeing separate movements coming out of this, with Pride month just around the corner, and other races uniting for the betterment of race relations in this country, we are seeing a world hurting and coming together, at a time where we’ve been so far apart for so long.