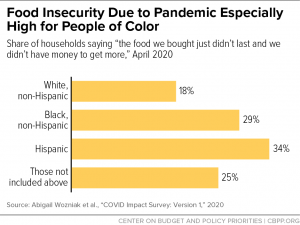

As our world grieves in the aftermath of the horrific murder of George Floyd, I have become extremely grateful for the knowledge about systematic racism my education at UW has afforded me. My greatest takeaway from this class was learning to think systematically about the world food system, which allowed me to realize how everything from climate change to land grabs to severe income inequality in the food distribution chain levies a disproportionate impact on people of color in their struggle to access affordable and healthy food. Through course content such as Lester R. Brown’s “Full Planet Empty Plates” we have learned that there is an abundance of food in America, yet the reason so many of our citizens go hungry is because of a lack of income, and ultimately, a lack of privilege in our capitalist system leading to the harshest impacts of food insecurity to be felt by POC and BIPOC communities.

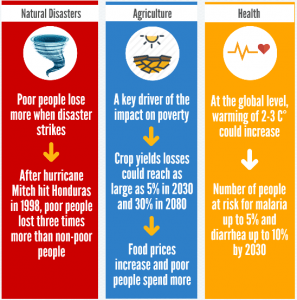

Much of my undergraduate education has been focused on race relations in the America, and I was able to incorporate this knowledge into my group work with Our Climate this quarter. We were given the opportunity to meet with Representative Tina Orwall, who has been a champion for racial equity throughout her career. We were able to advocate for bold, equitable climate change policy with a focus on the disparate impact of climate change on poor people of color. Representative Orwall was extremely receptive to our goals and told us that we had taught her new things about racism in the ecological system. From this, I became cognizant of my power of advocacy and sharing information, as Representative Orwall was able to get us in contact with other relevant politicians and added that she would further research and incorporate our findings into her agenda. Now as we are in the midst of a widespread Black Lives Matter movement, I find myself again as an advocate, and I have similarly been able to share useful information about the systematic racism in the world food system as part of the widespread sharing of resources against racism we are seeing. Just as we have achieved recent policy changes by educating our fellow advocates and putting pressure on our politicians, we are slowly dismantling systematic racism, and I am confident that if we can keep pressure on, we can one day create a just and equitable ecological system for all.