My group had the opportunity to work with Landesa; a non-profit organization that helps secure land rights for the world’s poorest. Although Landesa covers a more general scope, our focus was to bring awareness to the issue of women land rights in underdeveloped countries, and to learn more about how it connects to resilience-building within communities in the face of a pandemic.

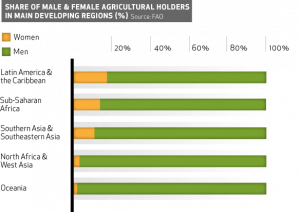

We learned that the women in the regions we researched make up the vast majority of the agricultural workforce, but due to the huge gender disparity, the lack of land rights puts women in vulnerable positions, especially when facing a health crisis. If the patriarch falls ill or passes away, there isn’t much a woman can do to support her family. At least not with the current system.

This quarter we talked about systems theory. We are all part of a system(s). If a part of the system is changed, then the other parts will be affected– impacting the system as a whole. This impact could either be negative or positive. Through our research we found that by giving women legal access to land, it could be the latter. They have the ability to help their communities build resilience by making an economic and ecological impact; all they need is change. The current status quo is an example of an unsustainable system.

Unsustainable systems are everywhere. We don’t have to go to an underdeveloped country to see them. Our food system is a big one.

Individual, institutional, and structural racism lives in our food system. In the reading, “The Color of Food”, Raj Patel concludes that racial disparity in wages and representation can be found in most occupations along the food chain. POC are often limited to low-wage food jobs in the food industry, leading them to experience high rates of food insecurity, malnutrition and hunger. But consumers are oftentimes unaware of these exploitations because there is a great disconnect between consumers and the food chain.

With the BLM movement in full force right now, it is important to understand that racism goes beyond just police brutality. It lives in different parts of our society.

As this class comes to an end and our projects wrap up, I can’t help but think about the systems I belong to and the impact I’m having on them. Raj Patel stated that, “consumers vote with their purchases”. As a consumer in this unsustainable system, my choices matter when it comes to food.