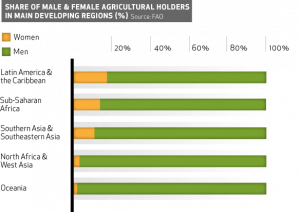

For our action project, we worked with Landesa. We focused our efforts on connecting the current pandemic to the role of women’s land rights and food security in Sub-Saharan Africa. We concentrated on this region, as it has faced the epidemics of HIV/AIDS and Ebola, and has had to overcome these crises while dealing with the ongoing natural problems that are endemic to the climate and region (drought and political instability). Additionally, the region has long-suffered from exploitation and pressures of global imbalances of power. What has become evident, is that developed countries are able to leverage local resources, which are developed and cultivated by African nations to advance their own stability and serve as a source of resilience. Against this backdrop, the region will continue to evolve as “an arena of geopolitical and resource competition…” and this can be problematic, as Africa may be disenfranchised from ‘solutions’ that are developed within the region. This is where the role of women’s land rights becomes a driver of law and policy reform and economic self-reliance and community leadership. Allowing women to have direct and impactful roles in the food system will foster a resistive and durable base that the communities of Africa can count on for stability and lean on in times of crises.

What I have recognized in Landesa is that many of the defining attributes and workings of systems theory are functioning through this organization and the work it is doing to make an impact on society. We were able to connect seemingly individual and distinct topics into an aggregate context relevant to human systems and, by extension, the ecosystem. (from lecture) What is common across developed, developing, emerging, and underdeveloped economies is growth. This trend towards an improved standard of living does not emerge in isolation. In this case, women’s land rights connect to all of us, even if we benefit indirectly. Through a woman’s ability to own and control land in Africa, the role of my country (or another developed country) will shift as it benefits from concurrent growth. And this shift can impact my community whether it is through the flow of money or access to food as a whole. We all benefit from socio-political stability, as instability can result in a misallocation of resources. Currently the IMF projects negative growth for the region through this year, but forecasts a return to positive growth through 2021.