December 12, 2023

Fiat Lux – By Daniel James Brown

Daniel Brown, author of The Boys in the Boat

The following is a version of a keynote speech given by author Daniel James Brown at the 2014 UW Libraries’ Literary Voices fundraising event that has been edited for length in this context.

PREFACE: Daniel Brown’s love of libraries began decades ago when, as a struggling high school student, he was instructed to complete correspondence courses while working out of Doe Memorial Library at Cal Berkeley—to earn his high school diploma. The experience was foundational. Speaking at a UW Libraries event, Brown reflected about this pivotal time and his early career as an English professor, where “university libraries were always my places of refuge, my sanctuaries—Doe and the Bancroft at Berkeley, Powell at UCLA, Clark at San Jose State, Green at Stanford. They were the places where I could most fully become who I was, who I am today.”

I have to confess that although I lived just across the lake in Redmond, I seldom had occasion to visit the University of Washington Libraries. But then, in 2008, I met my neighbor, an old man named Joe Rantz. When I first sat down with Joe and he began to tell me how he had come to row crew at the University of Washington and how he and his crewmates had won a gold medal in Berlin in 1936, rowing against a German boat in front of Hitler, I was mesmerized immediately.

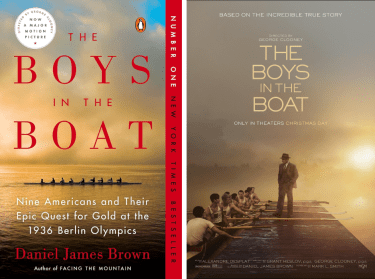

LEFT: The book cover for The Boys in the Boat; RIGHT: a promotional poster for the film, opening December 25, 2023.

And as Joe talked that first day, I couldn’t help but notice that from time-to-time he was tearing up. At first, I thought he was crying for the loss of his crewmates, most of whom had passed away in the preceding few years. But as we talked more I began to see that there was a kind of joy coming through Joe’s tears, a large measure of pride and love. And as we talked more, I began to understand that Joe was crying not so much for the loss of his crewmates as for the sheer beauty of what had happened seventy-five years before in Berlin. Toward the end of the conversation, I asked Joe if I could write a book about his life. He thought for a moment and then shook his head and said slowly, “No…I don’t want you to write a book about my life. But you can write a book about the boat.”

At first, I didn’t know what he meant—I thought he meant the physical boat in which he and his mates had rowed. But we talked a little more, and I gradually came to understand that by “the boat” Joe meant the other boys who had rowed with him. And then, finally, I came to understand that he meant more even than that. He meant the perfect thing that he and those eight other good-hearted boys had become together—a living thing, an almost mystical thing, an exquisitely unified and balanced thing, a team in the very deepest possible meaning of that word.

And so I set out, the very next day, with Joe’s permission, to write a book about the boys in the boat.

It didn’t take me long, though, to discover that the story was really about even more than just than those nine boys and a gold medal and the beauty of that moment in Berlin. It was about the mechanics of rowing, the physiology of pain, and the psychology of endurance. It was about humility and trust, about loss and redemption. It was about the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl and Nazi Germany and boat building and an Olympic boycott and a German filmmaker named Leni Riefenstahl and many, many other things about which I knew next to nothing.

The Reading Room in Suzzallo Library

But I did know where to go. And when I walked into Suzzallo Library at the University of Washington, I knew immediately that I was home again.

There were the old familiar smells, the ornate entrances and marble staircases, the murmuring of students, a great, cathedral-like reading room, and stacks and stacks of books.

Over the next several years, that first conversation I had with Joe Rantz became a book called The Boys in the Boat. But that happened only because of the vast collection of carefully preserved documents and artifacts I was able to unearth at Suzzallo.

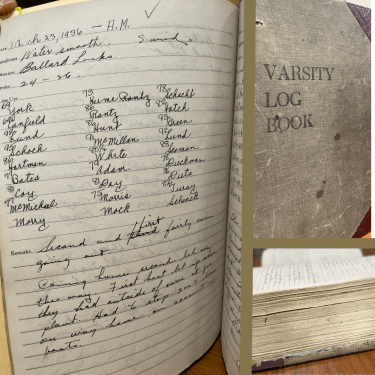

Images: A page from one of Coach Al Ulbrickson’s log books, March, 1936. From the Alvin Edmund Ulbrickson papers, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, accession number 2941-001

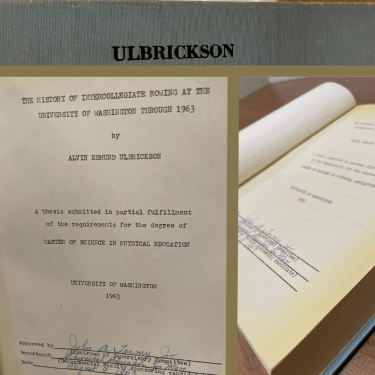

Images: Cover page and spine of the bound edition of Al Ulbrickson Jr.’s Master’s thesis on the history of Washington rowing. Special Collections, Thesis 12997

I found hundreds of relevant articles from The Seattle Times, the P-I, and UW’s Daily on microfilm. I found the daily logbooks of Coach Al Ulbrickson, some of them kept in old lab notebooks stained with mysterious chemicals but carefully conserved in Special Collections. I found a bound edition of his son, Al Junior’s, Master’s thesis on the history of Washington rowing. I found a trove of books on German history, sports psychology, the Depression, Riefenstahl, and dozens of other topics of interest—really pretty much everything I needed to get a firm grip on any angle of the larger story. There were hundreds of photographs—not just those that appear in the book—but scores more that gave me small but crucial insights into daily life in Seattle in the mid-1930s, many of them conveniently digitized.

I don’t think it is an overstatement to say that The Boys in the Boat would never have happened but for the resources housed in this one library.

These kinds of materials are the stuff from which new books are sometimes made—not just mine, but thousands of the new books that appear in the marketplace every year. I think too often we think of libraries only as repositories of old stories and old books; but in fact they are also very often the wellspring of new stories and new books.

Now we are here tonight, of course, because we have decided to join in a cause, to raise funds for the library. And that brings to mind an incident from The Boys in the Boat. The boys from Washington won the right to represent the United States at the 1936 Berlin Olympics in a qualifying race at Princeton on a sweltering hot day in June of 1936. But just a few hours after that victory—after they had realized the goal toward which they had striven for three years—an official from the Olympic Rowing Committee, a man named Henry Penn Burke from Pennsylvania, came to Coach Ulbrickson and informed him that the boys, or the university, would have to pay their own way to Berlin. And, Burke went on, if Washington couldn’t afford to go, the Pennsylvania boys had plenty of money. They had come in second. They would be happy to go in Washington’s place. Ulbrickson was flabbergasted, and furious. No one had ever suggested that the boys would need to pay their own way. This was the depths of the Depression and none of them had two nickels to rub together, nor for that matter did the University. Burke left the meeting with Ulbrickson under the impression that Washington could not afford to go. Ulbrickson left the room with the same impression.

Image: 1936 Olympic Games and Poughkeepsie Regatta Crew Champions (Joe Rantz is the second rower from the front), University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, UW37275. See also many of the iconic historical photos in a new UW Libraries digital collection: UW 1936 Olympic Rowing Team

But that night, phones began to ring all over Seattle. Ulbrickson and the Washington press contingent—Royal Brougham of the Post-Intelligencer and George Varnell of The Seattle Times—began placing calls back home and composing headlines for the morning editions of their papers. By the next morning, committees had been formed. By that afternoon hundreds of students and citizens were on the streets of Seattle selling paper badges for 50 cents apiece. Donations began to come in from businesses and individuals: $1.00 from a donor who wished to remain anonymous, $5.00 from the Hide-Away-Beer Parlor, a hefty $500 from The Seattle Times. By the time another twenty-four hours had passed, the citizens of Seattle had raised $5,000 and the boys were good to go to Germany. But only because the citizens of Seattle stood up and said, “Yes they will go.” It was, as someone pointed out to me recently, an example of Seattle’s 12th man before there was even a professional football team in the city.

It tells a story. It tells how—aided by the spectacular generosity of the citizens of Seattle in a very tough time—those nine young men showed us all what we can do when we climb in a boat and pull together as one.

The boys went on to win Olympic gold in spectacular fashion in Berlin. But they did more than win gold. They created a great legacy. If you have never done so, I urge you to go down to Conibear Shellhouse and take a look at the Husky Clipper, the beautiful shell in which the boys rowed their way to glory in 1936. It hangs gorgeously above the dining commons. It has been lovingly restored, preserved, and displayed. Its burnished red cedar hull and yellow spruce trim glow under the spotlights in the room. But more than a beautiful object, the Husky Clipper is important because it is a symbol. It stands for something far beyond winning a race. It embodies the boys’ legacy. It tells a story. It tells how—aided by the spectacular generosity of the citizens of Seattle in a very tough time—those nine young men showed us all what we can do when we climb in a boat and pull together as one.

The boys went on to win Olympic gold in spectacular fashion in Berlin. But they did more than win gold. They created a great legacy. If you have never done so, I urge you to go down to Conibear Shellhouse and take a look at the Husky Clipper, the beautiful shell in which the boys rowed their way to glory in 1936. It hangs gorgeously above the dining commons. It has been lovingly restored, preserved, and displayed. Its burnished red cedar hull and yellow spruce trim glow under the spotlights in the room. But more than a beautiful object, the Husky Clipper is important because it is a symbol. It stands for something far beyond winning a race. It embodies the boys’ legacy. It tells a story. It tells how—aided by the spectacular generosity of the citizens of Seattle in a very tough time—those nine young men showed us all what we can do when we climb in a boat and pull together as one.

And that’s just exactly what we are doing here this evening, climbing in a boat and pulling together as one toward a common goal—

providing for the restoration, conservation, and preservation of the library materials that remind us who we are, the materials that past generations have left us as their legacies, to tell us their stories, and to engender new stories.

And so the library—particularly the university library—remains the ultimate sanctuary of knowledge. And it is truly a sanctuary, a temple in which we keep the flame of knowledge lit. And we must defend it. It is up to us individually—but more importantly collectively, as a team, joining together as one, just like that 1936 crew—to keep that flame blazing brightly. As the motto over the portal of Doe Library down in Berkeley reminds every uncertain young man or woman who passes under it, generation after generation, Fiat Lux, let there be light.

###

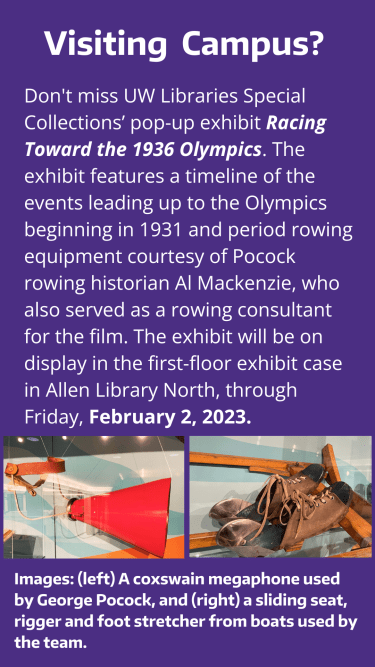

Learn more about how you can support UW Libraries.