For my action project, my group developed a set of news media and social media content to engage the public with the issues of dairy CAFOs in Washington. This included Facebook and Twitter posts, which had info graphics and in the future will have political tool kits for citizens to contact their representatives and the WA Department of Ecology during the legislative session, and letters to the editor which were sent to multiple local newspapers.

Figure 1: Example post from my action projects Facebook page

Figure 1: Example post from my action projects Facebook page

In this class we have discussed the impacts of COVID on the world food system. These impacts have largely been to processing and distribution. Our project was also impacted by COVID because we had less of an opportunity to spread our message. Our social media posts did not do as well as we had hoped because there is currently a lack of interest for this kind of content currently given both world an domestic events. This is not something that only we faced. During the pandemic, I have noticed that most environmental groups have shifted their focus from traditional targets to focus on causes related to the pandemic and more recently racial justice.

Figure 2: This image, posted on Greenpeace USA’s Facebook page, is an example of the shift in focus from environmental groups

Figure 2: This image, posted on Greenpeace USA’s Facebook page, is an example of the shift in focus from environmental groups

This is a unique issue that ties into the other impacts of COVID on the world food system which we discussed in class. The difference is that the impact of decreased pressure from advocacy largely affects production, and not as much processing or distribution. Production has been negatively impacted by the disruptions to processing and distribution however, unlike processing and distribution where COVID has pretty much only been a detractor, the production portion of the world food system has been avle to operate unchecked.

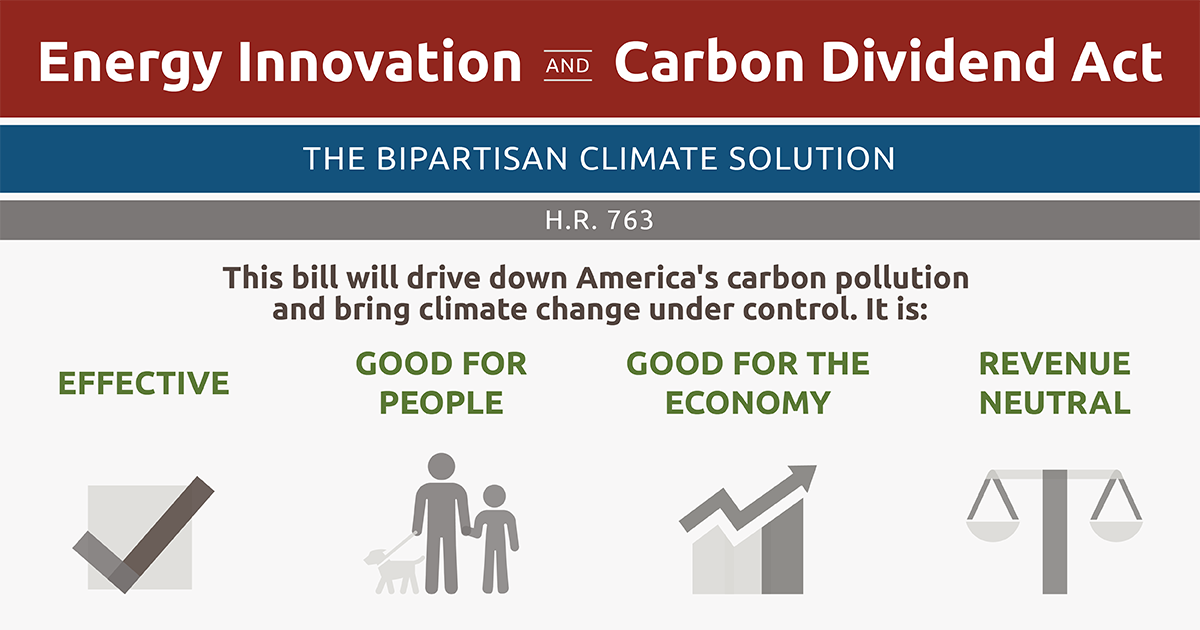

Figure 3: The recent increase in the rate of deforestation of the Amazon is an example of the impacts on the food system as a result of a distracted world. Source: NBC news

Figure 3: The recent increase in the rate of deforestation of the Amazon is an example of the impacts on the food system as a result of a distracted world. Source: NBC news

While advocacy from environmental groups may not play into the typical model for a world food system, a basic understanding of systems thinking, the discussions we have had in class, and my experience with my action project have allowed me to better understand the connections in our food web I didn’t know existed.