I chose to respond to Aaron Baker’s post “Is your Hunger Natural or Affluent?” (link: https://sites.uw.edu/pols385/2020/05/04/is-your-hunger-natural-or-affluent/). The question posed in his title is something I have been grappling with since I shifted to a plant-based diet due to unethical practices in the meat and dairy industry. I thought his response was very insightful, and I especially appreciated his statement “Just as hunger may be ubiquitous in the state of nature, it is equally possible for it to be absent entirely in a relatively affluent state in which the parameters of self-preservation have been redefined.” His thoughts made me consider how I drastically redefined my diet by only considering plant-based options as permissible for my self-preservation, despite there being ample other food options surrounding me. Thus, it seems as if I have redefined my “self” that I wish to preserve. My goal is not to simply keep myself alive, rather it is to maintain optimal nutrition, ethical consumption, and great taste.

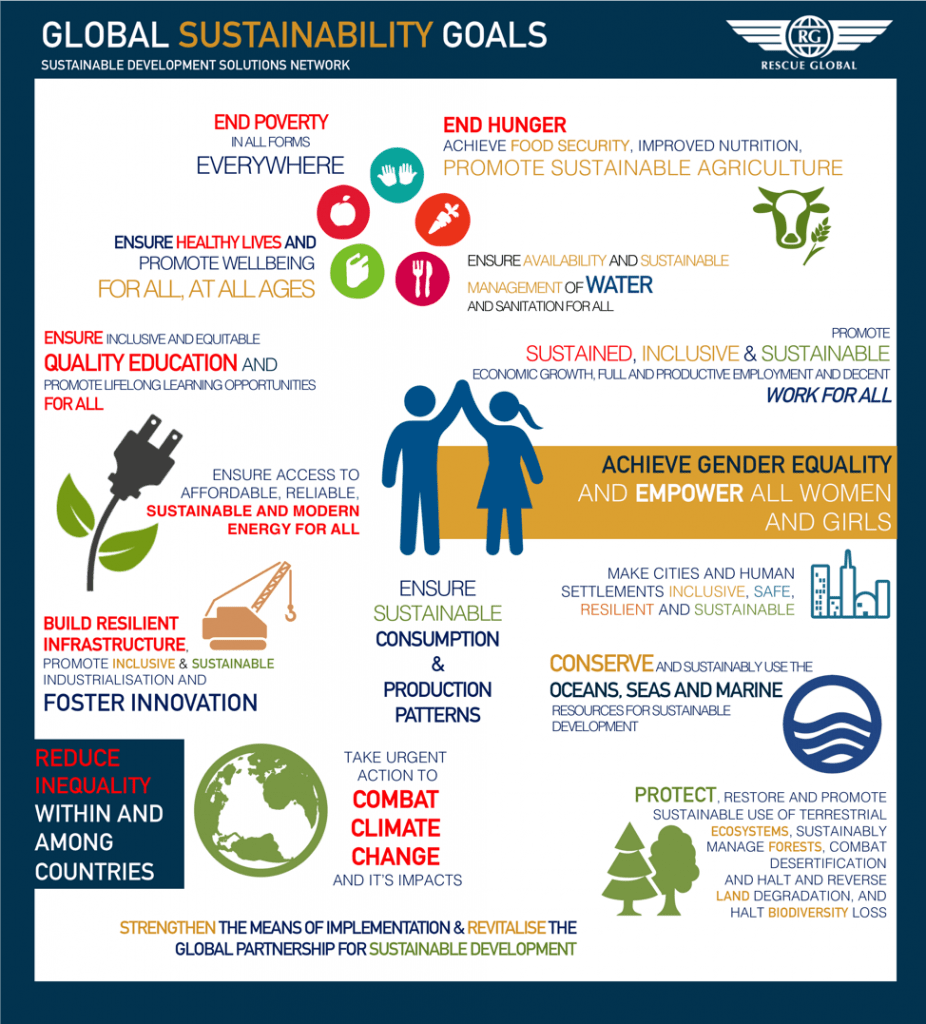

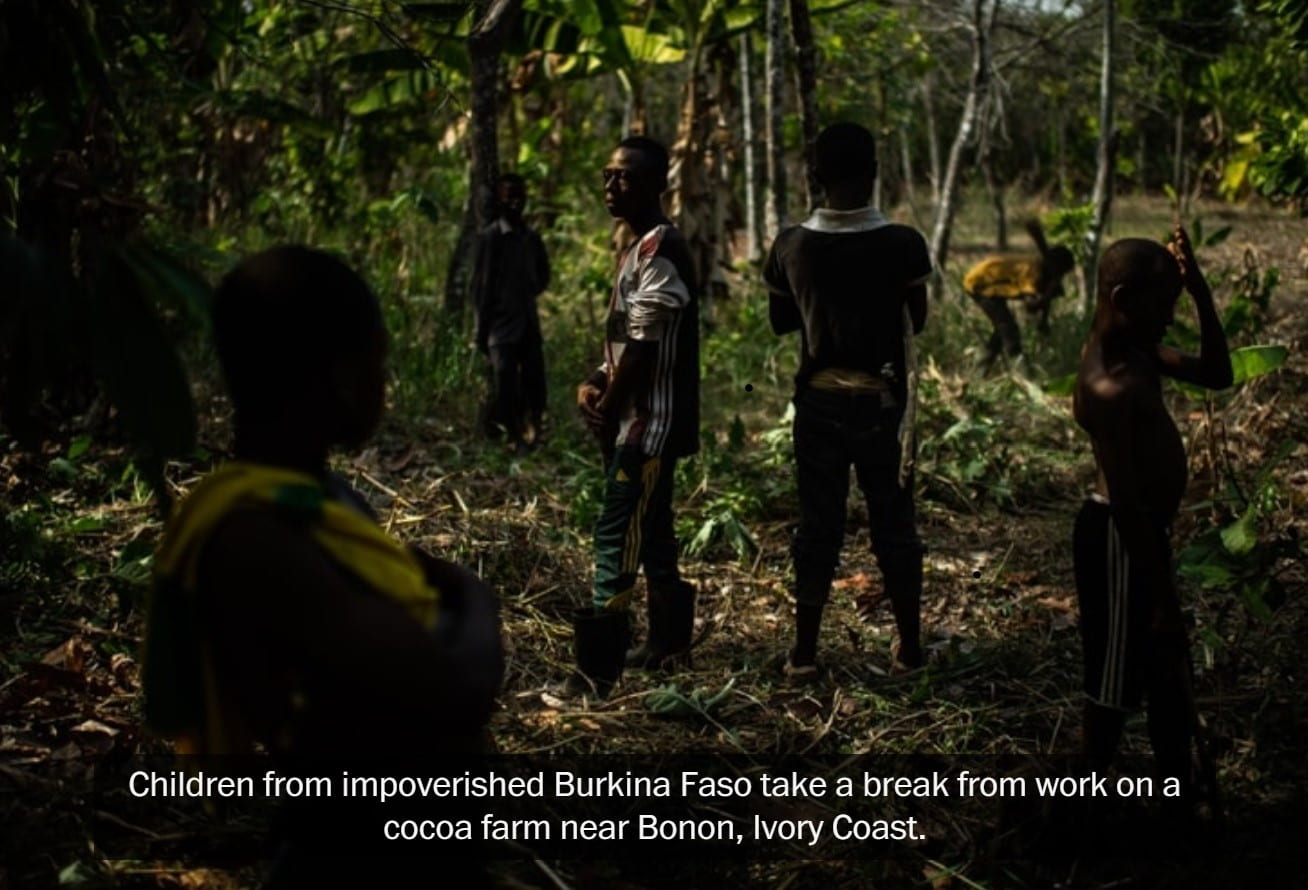

From this, I drew a connection to “The Color of Food” (https://canvas.uw.edu/courses/1372505/files/63044076/download?wrap=1) article we read in class, which described the “good food movement” amongst privileged middle-class individuals who prefer to consume organic food. The article goes on to describe those economically excluded from this movement, who rely on food supplied through the enormous food production chain that exploits people of color and “often forces workers to live in conditions that are close to poverty.” So, when I search for vegan meals, my hunger isn’t natural, it is affluent. Recognizing how much of the world struggles with food sovereignty allows me to stave off complacency as in my fight for change in the food system. I recognize a vegan diet isn’t enough, and that holistic change that provides everyone equal access to good food as I do today is my ultimate goal.