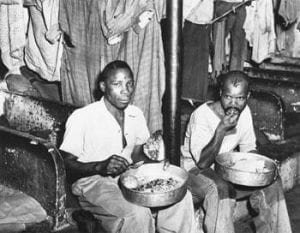

Figure 1: Granlund, 2011

With ever constant demands for my time, energy, and thoughts, I usually don’t stop and think deeply about where and how the food I consume is produced. A reoccurring theme of my feelings after contemplative practices were complicated emotions around my own complicity in global food injustices.

Never was this clearer to me than during the contemplative practice on chocolate. Watching the cocoa farmers experience eating chocolate for the first time, I knew it was just one of the many global food injustices propagated by a global trade system which values consumers in developed countries, over producers in developing countries. From countries experiencing famine contractually forced to export their food (Carolan, 2018), to rice originally smuggled and planted by West African slaves, returned to these countries in the form of contingent and domestically damaging “food aid”(Lecture 4/30), the systemic inequalities that I implicitly benefit from are all around me.

Initially, these contemplative practices filled me with a feeling of guilt and ineptitude considering the miniscule impact my individual actions could make on these globally propagated problems. Yet, as they progressed, I eventually came to a feeling of resolve.

Figure 2: Campesina 2020

While I can’t help cacao farmers in West Africa and may not be able to change global trade agreements on my own, I can still do something. I can acknowledge the privilege that I have and help bring these issues to the attention of my fellow citizens, who collectively can more effectively demand for more equitable international food politics and purchasing agreements such as getting more involved in the Food Sovereignty and Beyond Fair Trade movements.

Overall, these practices have shown me that I can and need to slow down and appreciate all the people whose lives went into supporting my own and do my part to make their lives a little bit better.

Sources:

Campesina, La Via. “Till, Sow and Harvest Transformative Ideas for the Future! Now Is the Moment to Demand Food Sovereignty – #17April.” Focus on the Global South, 16 Apr. 2020, focusweb.org/till-sow-and-harvest-transformative-ideas-for-the-future-now-is-the-moment-to-demand-food-sovereignty-17april/.

Carolan, Michael. “Cheap Food and Conflict.” The Real Cost of Cheap Food, Routledge, 2018, p. 78.

Granlund, Dave. “Dave Granlund – Editorial Cartoons and Illustrations>.” Dave Granlund Editorial Cartoons and Illustrations RSS, www.davegranlund.com/cartoons/2011/07/27/obesity-and-famine/.