This past quarter I had the opportunity to work with a Washington organization fighting to empower the youth of the state to fight for bold, equitable, and science-based climate policies. Through my work with Our Climate, coupled with my politics of the world food system course, I became more educated about the concentrations of power in wealth that dominate and dictate the processes and practices of the world food system.

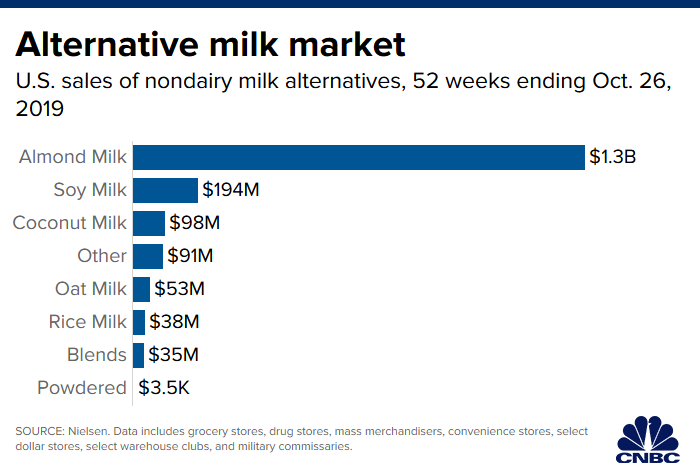

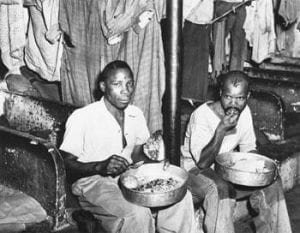

The richest fifth of the population control 90 percent of the world’s wealth and emit 80 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.[i] This block of people is mostly white. This fact does not exist without substantial consequences for the rest of the population. For example, 10 percent of white households experience hunger in the United States, Black households experience hunger at rates of 20-25 percent.[ii]

Source: https://alliancetoendhunger.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Hill-advocacy-fact-sheet__HUNGER-IS-A-RACIAL-EQUITY-ISSUE_Alliance-to-End-Hunger.pdf

Food insecurity, as we know can and does lead to inability to attend school or jobs, decreased health and health outcomes, disease, shortened life expectancy, and more. Systemic racism does not solely exist in our legal and governmental institutions. It shows up in the global food system, especially in the American food system. Systemic racism is not isolated to a few systems or institutions, food insecurity is not the only manifestation of systemic racism. Private agricultural land ownership is dominated by white people.[iii] Only 1.3 percent of farmers in America are Black.[iv] Black farmers receive less assistance from the government than white farmers.[v] The list goes on and on.

Systems are inherently interconnected and organized to achieve a function. Yet, our national food system fails Black Americans. Change in systems is inevitable and we must leverage this inherent change to ensure that food systems serve Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color just the same as they serve white people. We must call upon our politicians and listen to Black activists to address these issues.

Lastly, I want to share some important resources, activists, educators, and organizers to turn to during this time.

- Robert Bullard (https://drrobertbullard.com/)

- Majora Carter (http://www.majoracartergroup.com/)

- Dianne Glave (https://www.chicagoreviewpress.com/rooted-in-the-earth-products-9781556527661.php)

- Karen Washington (https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/may/15/food-apartheid-food-deserts-racism-inequality-america-karen-washington-interview)

- An Annotated Bibliography on Structural Racism Present in the U.S. Food System, Michigan State University: https://www.canr.msu.edu/foodsystems/uploads/files/Annotated%20Bibliography%20on%20Structural%20Racism%20in%20the%20US%20Food%20System%205th%20Ed.pdf

END NOTES:

[i] Political Ecology of the World Food System Lecture, April 16, 2020

[ii] https://alliancetoendhunger.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Hill-advocacy-fact-sheet__HUNGER-IS-A-RACIAL-EQUITY-ISSUE_Alliance-to-End-Hunger.pdf

[iii] https://foodfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/DRnumber2_VF.pdf

[iv] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/apr/29/why-have-americas-black-farmers-disappeared

[v] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/apr/29/why-have-americas-black-farmers-disappeared

– Sophie Stein