Original Post: https://sites.uw.edu/pols385/2020/04/13/migrant-workers-are-the-backbone-of-our-food-system-why-dont-we-treat-them-better/

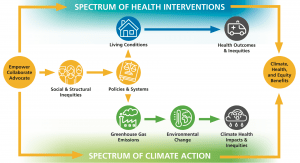

The United States has a long history of social inequity and it is coming to light more during the recent events of COVID-19. I do agree with Ag519 with the unjust treatment of migrant workers especially during this time and the fact that things aren’t getting better. I do have an answer to their question on why it is not getting better. Upper class society has a substantial amount of power over what happens in this world, and they do not want to lose this power. With that, all they worry about is how to gain more money and power and finding the quickest way at attaining that. In addition to that, there is barely any media coverage around big social problems in the world, so only a small amount of people knows what’s happening.

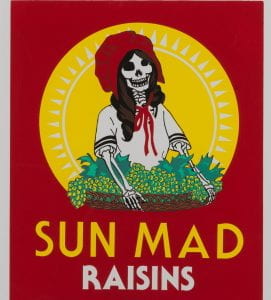

The video So Close to America: Undocumented Farm Workers & The Myth of The ‘Free Ride’ illustrates how migrant workers work just as hard, if not harder, than other people in America while doing the jobs no one else wants to do. During this time, migrant workers continue to work in close quarters with each other and do not have resources to stay safe while others can work from home or not work at all. A question that I think Ag519 does not ask that is very important is what can we do as a community to change this. What can we do as allies to support migrant workers and what can we do to change the system? This is an important question because it asks where we go from here. These answers can include educating others about the unjust treatment happening, especially during this pandemic and donating to foundations in support.

Change starts with everyone fighting together against inequity and unjust treatment.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/59692373/GettyImages_968561996.6.jpg)