By focusing on dumped milk, you showed concern in your blog about the food waste before and amid the COVID-19 pandemic. I agree with you that as the coronavirus spread rapidly across the world, it is disrupting our supply chains and making farmers grappling with low prices and an abrupt drop in demand. Because of the lockdown, restaurants and grocery stores are shutting down and farmers are forced to destroy their crops, throw out perishable items, and dump excess milk. According to estimates from the largest dairy cooperative in the US, dairy farmers are dumping out approximately 3.7 million gallons of milk per day due to the pandemic.

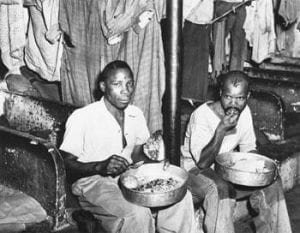

With restaurants and schools closed because of the stay-at-home order, it is inevitable that we will experience a hard time managing soaring food waste. One way to alleviate this problem, from my perspective, is to donate the excess food to food aid programs such as SNAP. Also, the government should allocate compensation fairly to farmers to help them go through this hard time. As we’ve discussed in class, inequalities in the food system over time are magnified and are especially obvious during this pandemic. While coronavirus is devastating agriculture, the most vulnerable and impacted groups are low-income families and undocumented workers. As they rely more heavily on SNAP and other food aid during the pandemic, donating excess food can not only ensure enough food supply for SNAP but also abate food waste pressures.